The US Department of State in a report said Bangladesh constitution provides for freedom of speech, including for the press, but the government sometimes failed to respect this right.

“There are significant limitations on freedom of speech. Many journalists self-censored their criticism of the government due to harassment and fear of reprisal,” said the report titled ‘Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2020’.

The report released recently is an annual documentation of the state of human rights across the world. The report touched on various aspects including denial of fair public trial, arbitrary arrest or detention, torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

The report said the law limits hate speech but does not define clearly what constitutes hate speech, which permits the government broad latitude to interpret it. The government may restrict speech deemed to be against the security of the state; against friendly relations with foreign states; and against public order, decency, or morality; or which constitutes contempt of court, defamation, or incitement to an offence. The law criminalices any criticism of constitutional bodies.

The 2018 Digital Security Act (DSA), passed ostensibly to reduce cybercrime, provides for sentences of up to 10 years’ imprisonment for spreading “propaganda” against the Bangladesh Liberation War, the national anthem, or the national flag, according to the State Department.

On 16 April, the Department of Nursing and Midwifery banned nurses from speaking to the press after the media reported the health sector’s lack of preparation in managing COVID-19.

On 23 April, health minister Zahid Maleque banned all health officials from speaking with the media.

On 13 October, the home ministry issued a press release restricting “false, fabricated, misleading and provocative statements” regarding the government, public representatives, army officers, police, and law enforcement through social media in the country and abroad. The release said legal action would be taken against individuals who did not comply, in the interest of maintaining stability and internal law and order in the country.

During the week of 3 May, press outlets reported at least 19 journalists, activists, and other citizens were charged under the DSA with defamation, spreading rumors, and carrying out anti-government activities. Media accounts of a police case report involving 11 accused individuals detailed Rapid Action Battalion search of mobile phones of two accused and found “anti-government” chats with other accused individuals. According to the police, these “anti-government” chats sufficed as evidence to charge and detain the individuals under the DSA.

Both print and online independent media were active and expressed a wide variety of views; however, media outlets that criticized the government were pressured by the government.

The government maintained editorial control over the country’s public television station and mandated private channels broadcast government content at no charge to the viewer. Civil society organisations said political interference influenced the licensing process, since all television channel licences granted by the government were for stations supporting the ruling party.

Authorities, including intelligence services and student affiliates of the ruling party, subjected journalists to physical attacks, harassment, and intimidation, especially when tied to the DSA.

The DSA was viewed by human rights activists as a government and ruling party tool to intimidate journalists. The Editors’ Council, an association of newspaper editors, stated the DSA stifled investigative journalism. Individuals faced the threat of being arrested, held in pretrial detention, subjected to expensive criminal trials, fines, and imprisonment, as well as the social stigma associated with having a criminal record.

On 10 April, during the government instituted lockdown to control COVID-19 transmission, a police constable from Hazaribagh police station beat Nasir Uddin Rocky, a journalist with Daily Jugantar, and his brother Saifuddin Quraish, a health worker, even though both men had cards around their necks identifying themselves as essential workers. Officials relieved the constable of his duties, and non-governmental organisations (NGO) reported the police had initiated an investigation into the case.

Independent journalists and media alleged intelligence services influenced media outlets in part by withholding financially important government advertising and pressing private companies to withhold their advertising as well. The government penalised media that criticised it or carried messages of the political opposition’s activities and statements. In September a group of media experts, NGOs, and journalists said the downward trend of the rule of law and freedom for the media went hand in hand with government media censorship, which, in civil society’s view, translated to the government’s distrust of society.

According to some journalists and human rights NGOs, journalists engaged in self-censorship due to fear of security force retribution and the possibility of being charged with politically motivated cases. Although public criticism of the government was common and vocal, some media figures expressed fear of harassment by the government.

Libel, slander, defamation, and blasphemy are treated as criminal offences, most commonly employed against individuals speaking against the government, the prime minister, or other government officials. As of July, 420 petitions requesting an investigation had been filed under the Digital Security Act with more than 80 individuals arrested. Law referring to defamation of individuals and organizations was used to prosecute opposition figures and members of civil society.

Atheist, secular, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) writers and bloggers reported they continued to receive death threats from violent extremist organisations.

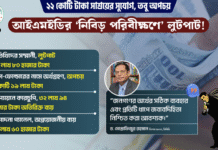

During June and July, the RSF reported a number of societal attacks against journalists, many in connection with anger over published reports with allegations of corruption and nepotism in the government’s COVID assistance response.

According to the RSF, 10 men assaulted journalist Shariful Alam Chowdhury with steel bars, machetes, and hammers. During the beating, Chowdhury’s arms and legs were broken. Chowdhury’s family told the RSF they believed local village council authorities called for this attack.