There is nothing liberal about calling for execution without regard to due process.

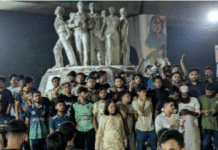

![Execution of Nizami bodes ill for Bangladesh's future Members of Ganajagaran Mancha hold a photo of the convicted Nizami, in front of the central jail before his execution on May 10 [EPA]](http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2016/6/6/8dfab728f29741d28b0c0542f2912a5e_18.jpg)

In May, the Bangladeshi government executed the most high-profile person convicted of war crimes. This execution bodes ill for future of the country.

Motiur Rahman Nizami, the chief of Jamaat-e-Islami, the country’s largest Islamic political party, was accused of war crimes committed during Bangladesh’s war of independence in 1971.

However, the legal framework underpinning the tribunal and its conduct has come under severe criticism from international bodies including the United Nations and all major human rights organisations.

|

| Bangladesh hangs Motiur Rahman Nizami for war crimes |

Atrocities on both sides

Bangladesh’s war of independence was a bloody affair. While there is no agreed account of the scale and extent of the crimes committed, neutral observers have accepted that gravecrimes were committed on both sides.

Although atrocities committed by the Pakistani army and their collaborators are well known in the West, less discussed are the lynch mobs and reprisals against those opposing independence.

One of the enduring images that came from this time was that of the Mukti Bahini, or the freedom fighters, bayoneting suspected collaborators for the Pakistani army.

Prominent Bengalis who opposed independence were forced to flee, go into hiding or face a brutal backlash including being tortured and murdered.

Though narratives coming from that time are polarised, the grievances surrounding the 1971 war are real and the need for closure to that period of Bangladesh’s history is necessary.

Such calls are usually associated with the pro-independence bloc which has actively called for the current war crimes process. Yet, there is consensus and wide support for a fair, transparent and robust trial.

Indeed, almost all of the accused, including Nizami, had expressed their readiness to clear their name in front of a proper and fair trial which upholds international standards.

Unfortunately, in addition to failing to meet fundamental requirements for a fair trial, the current tribunal’s jurisdiction is only to try the Bengalis who collaborated with Pakistan army.

Flawed justice and political show trial

Nizami’s trial – like those before and after him – is riddled with flaws (PDF). And sadly, the evidence is overwhelming to support claims that many of these flaws are intentional to predetermine the outcomes of these trials.

This was given credence by leaked conversations of Nizamul Haque Nasim, the chairman of the tribunal, with a Brussels-based Bangladeshi lawyer linked to previous campaigns against some of those facing trials.

Some of the conversations were specific and serious, which essentiallyamounted to a tri-party collusion between government, judiciary and pro-independence campaigners to predetermine outcomes of the trials.

The current chief justice who chaired the Appellate Division bench in Nizami’s verdict was named in one of the leaked conversation as a party to the whole collusion.

However, the tribunal’s most serious flaw is its consistent imposition ofsevere restrictions on the accused to produce witnesses in their defence.

For example, 16 charges against Nizami were all serious and carried the death penalty. These charges were related to numerous events, which were not necessarily factually or geographically linked. Yet, Nizami was only allowed to call four witnesses.

An ‘uncivil’ civil society

The failure of the judiciary to facilitate justice is compounded by Bangladesh’s dysfunctional civil society.

The trials exposed how “uncivil” its civil society really is. Criticisms of the legal framework and conduct of the trials had come from numerous quarters.

Yet, Bangladeshi media and civil society have either ignored these criticisms or accused those criticising of acting on Jamaat’s instructions.

Moreover, Bangladesh’s “secular” establishment – writers and intellectuals – have used their pens to extol the virtues of these trials, while branding opponents as Islamists for daring to quibble over the rule of law.

They were aided by mass demonstrations organised by the Ganajagaran Mancha, the group that has been consistently vocal in demanding the death penalty for the war criminals of 1971.

While in the West they continue to be celebrated as the vanguard for secular and liberal values, they are anything but – a mass, reminiscent of lynching mobs that came together demanding the execution of the 1971, accused without any regard for due process.

The movement was kicked off when it tried to put pressure on the Supreme Court of Bangladesh to change the life sentence verdict on one of the accused, Abdul Quader Mollah.

While the Bangladeshi government has cracked down and prevented mass rallies opposing these executions, they have allowed and often facilitated this “liberal” and “progressive” platform which has since celebrated every execution that has taken place on the streets.

Clash of values

Some see the war crimes tribunals in Bangladesh as ultimately the clash of progressive secular liberalism and the regressive, increasingly militant Islamic puritanism.

The government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has used this misconceived notion to her maximum advantage. In strange ways her hands have been strengthened by a series of unfortunate and barbaric killings of individuals, activists and authors known for their unconventional – and at times – highly contested opinions about Islam and Muslims.

These incidents, together with several killings of people from minority faith groups, have supported the claim of a clash between rising Islamic extremism and increasingly “threatened” secular liberal tradition.

OPINION: Citizens are also responsible for Bangladesh violence

However, this clash of values is a false dichotomy. Bangladesh’s Islamic political forces have many flaws, but a leaning towards violence or hatred of minority faith communities is not one of them.

Killing, violence and attacks on minority communities are too common in Bangladesh and have been for many years. While none of them has ever been properly investigated, and the perpetrators never tried in a judicial process that can withstand international scrutiny, the fingers have often been pointed to the politicians belonging to the ruling party for orchestrating such violence.

Moreover, there is nothing liberal about calling for an execution without regard to due process, suppressing free speech, stifling political opposition or enforcing blackout of media coverage of those the “liberal” elites disapproves. That only re-enforces the illiberal mentality and attitude the secular-liberals claim to be fighting against.

What the future holds

The reality on the ground – influenced by complex political interests, challenging economic reality and a fast-evolving society – makes any prediction or, indeed, suggestion for progress harder.

With the scope for free speech all but squeezed, the prevailing sociopolitical view is giving life to intolerance.

However, the Bangladesh government, media and civil society alone are not to be blamed. The international community – inter-state organisations, pressure groups and media – have all been too willing to accept a simplistic narrative of secular liberalism versus rising Islamist extremism as the real problem in Bangladesh.

This is evident from the international attention given to the horrific murders of a handful of activists whose causes resonated with Western society.

Even though their murders were rightly condemned and given attention to, hundreds of others continue to be victims of political murder and violence – especiallywhen they belong to one of the Muslim religious parties or groups.

But their plight is hardly recorded in the international media. This is despite them being targeted and killed for holding a certain socio-political view.

In turn, Bangladeshi centre-right and religiously inspired activists view Western civil society and the media with mistrust. Extremists have preyed on this, questioning the value of democracy in ensuring their rights and liberty.

Source: Al Jazeera