The arrest of two of Bangladesh’s foremost human rights activists has brought to light the country’s severe crackdown on journalists and NGOs.

Increasingly oppressive information laws in Bangladesh now mean that anyone arrested for publishing information that the government sees as damaging to its image, faces up to 14 years in prison and can be arrested without charge.

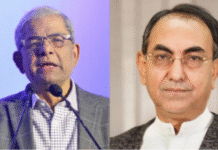

Last week, Nasirrudin Elan, director of Odhikar, a Bangladeshi human rights protection organisation, was arrested, and is being charged with disseminating false information under the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act. The charge comes after Odhikar published a report on their website, which claimed that 61 people had been killed by police in a protest in the capital, Dhaka, on May 5 and 6. The protest was organised by Hefazat-e Islam, an umbrella group of several Islamist organisations calling for the imposing of a stricter Islam in Bangladeshi society.

The government, however, claimed that only 11 people had been killed, and only after provoking the police. The ICT Act, undertaken by the Bangladesh National Parliament in 2006, says: “If any person deliberately publishes or transmits or causes to be published or transmitted on a website or in electronic form any material that is fake and obscene … and prejudices the image of the state or person or causes to hurt or may hurt religious belief … then this activity will be regarded as an offence.”

However, Elan’s arrest is even more significant because it occurred soon after an amendment that did not go through due parliamentary process and which has been deemed by local activists to violate his human rights.

Elan is the second Odhikar member to be arrested for this crime regarding the May protests. On August 10, secretary of Odhikar, Adilur Rahman Khan, was picked up by plain clothes policemen, held in prison for two months, and then granted bail on October 8. It was during his custody that the amendment was passed, just before his release.

The amendment, approved in Parliament on October 6, enables law enforcers to make an arrest without a warrant, and increases the minimum jail term for the offence to seven years, and the maximum from 10 years to 14 years. The amendment was approved by the Awami-League government without the presence of opposition MPs.

Fear

This means that Elan can be held for as long as the police see fit. On November 17, both he and Khan will appear before the Cyber Crimes Tribunal, set up specifically to adjudicate on the ICT act.

A report by Human Rights Watch says that 150 people in Bangladesh have been killed in protests from February to May 2013, including 7 children and 13 members of the security forces. Two thousand people have been injured.

“Security forces used rubber bullets and live ammunition improperly or without justification, killing some protesters in chaotic scenes, and executing others in cold blood. Many of the dead were shot in the head and chest, indicating that security forces fired directly into crowds. Others were beaten or hacked to death.”

The security forces are made up of the police, Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), and the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB).

Activists have also expressed fear at the risk of torture faced by Elan. In a letter from the Asian Human Rights Commission to the United National High Commissioner for Human Rights, the commission calls for help on what they call an “endemic affliction” in Bangladesh.

“Policing and torture are synonymous. The arrest of a person by the police or any law-enforcement agency of the country is understood to mean torture and ill-treatment of the arrestee right from time the act of arrest begins being executed,” reads the letter.

Lucky ones

In an interview on Thursday, after Elan was sent to jail, Khan says: “on August 10, the day after Eid, I was returning with my family from a friend’s place, entered my gate and 12 men dressed in civilian clothing pushed me inside. Without producing any ID or warrants they ordered to come with them. One of them mentioned that they were from the detective branch.”

He was then taken to the Dhaka detective branch, and was held in custody, initially with no access to lawyers.

“Even now, the judge has not allowed our lawyers to go through the documents,” says Khan.

“I have not been allowed to sign for power of attorney, for filing an application under the Writ Jurisdiction and for a long time I was obstructed from getting legal support.”

Tor Hodenfield, policy and advocacy officer at Civicus, an international alliance aimed at strengthening civil society, says that “in Bangladesh, there are legitimate concerns about the independence of the judiciary. And provisions (under the ICT Amendment Act), enable government with a prominent tool to detain and even [make] human rights activists disappear.”

Khan acknowledges that he was one of the lucky ones, thanks to the the loud voice of Odhikar and human rights activists across the country.

“There are many political detainees in prison,” he says. “Our criminal justice system is in such a shape that getting justice for ordinary people is very difficult to access. Our prisons are overcrowded, and when there is political unrest, you get five times more prisoners than capacity.”

New law

While the voice of NGOs and civil society are not acknowledged by the government, a new law has been passed that makes them even more vulnerable to closure.

A draft NGO law has been implemented under vague circumstances, even though it has not yet been passed in Parliament. The law makes it very difficult for any NGOs to receive any foreign funding, due to “terror-financing and other anti-government activities” In 2012, the NGO Affairs Bureau cancelled 6 000 new NGO registrations and was re-examing the licenses of 4 000 existing NGOs.

“Everytime elections become closer, the government starts to panic,” says Khan.

“They enacted the ICT Act in 2006, just before the elections. Authorities have pulled down so many dissenting voices through their crackdown. This makes it difficult for activists to raise their voice because they might end up in prisons.’

“More and more South Asian countries have been implementing more stringent security laws, in the name of countering terrorism, and the victims are the bloggers, the human rights activists, the media and the dissenters.”

Social media sites

The arrests and trial of Elan and Khan are not isolated. With the upcoming election, there is an increasing number of strikes, leading to increased police violence. Several opposition newspapers and television channels have been shut down during and after these incidents of violence, have experienced attacks of vandalism and arson with no police investigation, and many editors, journalists and bloggers have been arrested.

Hodenfield says that the crackdown on dissenting information in Bangladesh is representative of the same issues increasing in other countries around the world, where information dissemination has been deemed illegal under different laws.

“In the past few months, governments around the world have continued to crackdown on activists who are using social media sites. The arrests of civil society activists for using social media sites is becoming more and more common and governments in many countries are enacting stricter and more draconian legislation to control this new public space for social change. In Kuwait, the Court of Appeals upheld a 10-year prison sentence for Hama al-Naqi for using blogging sites. In Algeria, Abdelghani Aloui was arrested for putting caricatures on Facebook.”

Khan says that “things will only get worse” as the election gets nearer. “The state is becoming a police state,” he says. “If you criticise the Constitution you will get the highest punishment. This is contradictory to human rights free speech and freedom of expression.”

Source: Mail & Guardian