Bangladesh: As protests subside, authorities are using onerous digital laws to target demonstrators

‘None will be spared’: students fear reprisals over Bangladesh unrest

Michael Safi and Shaikh Azizur Rahman

Fri 10 Aug 2018

Demonstrations in Dhaka, Bangladesh, started as a demand for better road safety and spiralled into a larger expression of frustration against corruption and the government. Photograph: Monirul Alam/EPA

The list began spreading from phone to phone on Saturday, just as police were starting to fire teargas and rubber bullets at protesters in Dhaka demonstrating for safer roads.

“Please pass these addresses to trusted people through Messenger or text message,” it read. Names, phone numbers and locations were listed: sanctuaries for students fleeing a police crackdown.

“If anyone needs shelter around Jigatola or Dhanmondi, come to my place,” one student wrote.

“Take shelter please – the situation is getting worse,” said another.

The next day, as armed men alleged to be supporters of Bangladesh’s ruling party entered the fray, beating protesters and journalists, more people added their names and addresses to the list.

Then police started raiding their homes.

Wazir, a recent high school graduate involved in the protests, was on a Facebook thread with several students who had listed their houses as shelters.

Shortly after midnight on Sunday, one of them, Mahmoud, suddenly exited the thread. Photos and posts began to disappear from his Facebook wall. The group began to fill with panicked messages. Why had he vanished?

“He’s doing the smart thing,” one of the boys wrote. “He’s saving us.”

The Bangladeshi capital was paralysed for nine days, starting at the end of July, by protests involving tens of thousands of students.

Triggered by the killing of two schoolchildren by a minibus, the demonstrations started as a demand for better road safety, but spiralled into a larger expression of frustration against corruption and government impunity.

As protests have subsided in the past 48 hours, many of the students involved now fear reprisals from a government that rights groups say is becoming increasingly intolerant to opposition.

The same social media posts they used to organise and fan the demonstrations could serve as evidence to arrest dozens under Bangladesh’s onerous digital communications law.

Police used teargas and rubber bullets against protestors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Photograph: Munir Uz Zaman/AFP/Getty Images

“We are in the process to identify all those who spread rumours in the social media and incited violence,” Bangladesh’s home affairs minister, Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal, said on Wednesday. “None will be spared, be they students, teachers or political leaders.”

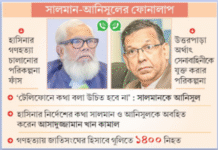

Mohammad Najmul Islam, an official in the cyber crime division of the Dhaka metropolitan police, told the Guardian officers had identified up to 1,200 social media accounts he said were used to spread rumours that encouraged violence and unrest.

“It will take some days before we finish our work on all of the users,” he said. “We have already booked 10 or 12 people who went live on Facebook during the protests to spread rumours. Others will face action soon.”

As his friends feared, Mahmoud’s home was raided by police on Sunday night. He tried to scrub as much of his Facebook content as possible before they got to it. The student, who attends a private New York university, was questioned but not arrested.

In the hours after the crackdown commenced on Saturday, accounts that had been actively cheering the protests fell silent. One student who had been involved in the protests from the beginning abruptly deleted her posts, writing a new one in formal Bangla. “I am sorry. I spread false statements. I was emotional,” she wrote.

She soon deactivated her account, telling friends in a message exchange seen by the Guardian she was leaving Dhaka for her own safety.

“They called my dad and said horrendous things,” she wrote. “‘We’ll blablabla your daughter in front of you.’ My mother is terrified and moving me elsewhere now.”

Wazir then heard another student who had been posting fierce denunciations of the government was also raided in the early hours of Monday. He had deleted pictures and posts from his Facebook account. “Brother, are you okay?” Wazir wrote to him on Facebook Messenger.

“Yes,” he replied, posting a smiling emoji. “How is life?”

Wazir was suspicious. “I said I was fine. He said, ‘That’s good’. And that was it.” He believes the account was being monitored.

It was not just the young protesters who weaponised social media during the unrest. Members of a pro-government student movement, the Chatra League, asked followers to send examples of anyone they thought were pushing false rumours.

Posts featuring the names and pictures of alleged activists were spread across Facebook and Instagram. One showed the pictures and names of four women. “These persons spread rumours and incited soft children to indulge in violence,” it said.

Police detained the photographer Shahidul Alam, on Sunday, citing an interview he gave to Al Jazeera and posts on Facebook during the Dhaka protests. Photograph: Monirul Alam/EPA

Leaders of the Chatra League also appeared in Facebook Live broadcasts alongside people purporting to be students, who hung their heads and gravely “confessed” to spreading lies against the government and police.

Dhaka has the second highest number of Facebook users per capita of any city in the world. As elsewhere, social media is providing public channels for dissent that might otherwise have been heard only been muttered to a few others at a tea stall or inside a home. Human rights groups say the Bangladesh government is overreacting in response.

In 2013 it amended the country’s digital communications law to make it easier for police to arrest those suspected of vague offences, such as publishing material that “tends to deprave or corrupt” or “causes or may cause hurt to religious beliefs”.

Since then, arrests and prosecutions have soared, according to Human Rights Watch, with more than 1,270 charge sheets lodged in the past five years. The government acknowledges the law is being misused but is yet to repeal it.

On Sunday night, police detained one of the country’s most prominent photographers, Shahidul Alam, charging him under the act, citing an interview he gave to Al Jazeera and posts on Facebook during the protests.

“The law is so vague that it can be used to punish anything said or written that the government doesn’t like,” said Omar Waraich, the south Asia director for Amnesty International.

“And if it can be used against someone of Shahidul Alam’s profile, the fear is that it will also be used against young people expressing peaceful views online.”

Many students in Dhaka have stopped posting about the protests online. One, Mahmudun Snabi, said many of those who took the streets last week were now panicking.

“Police are tracking people down and arresting people for sharing the news,” he said. “This is a very scary moment for all of us. No one has ever witnessed something like this on such a large scale.”