India’s biggest minority grows anxious about its future

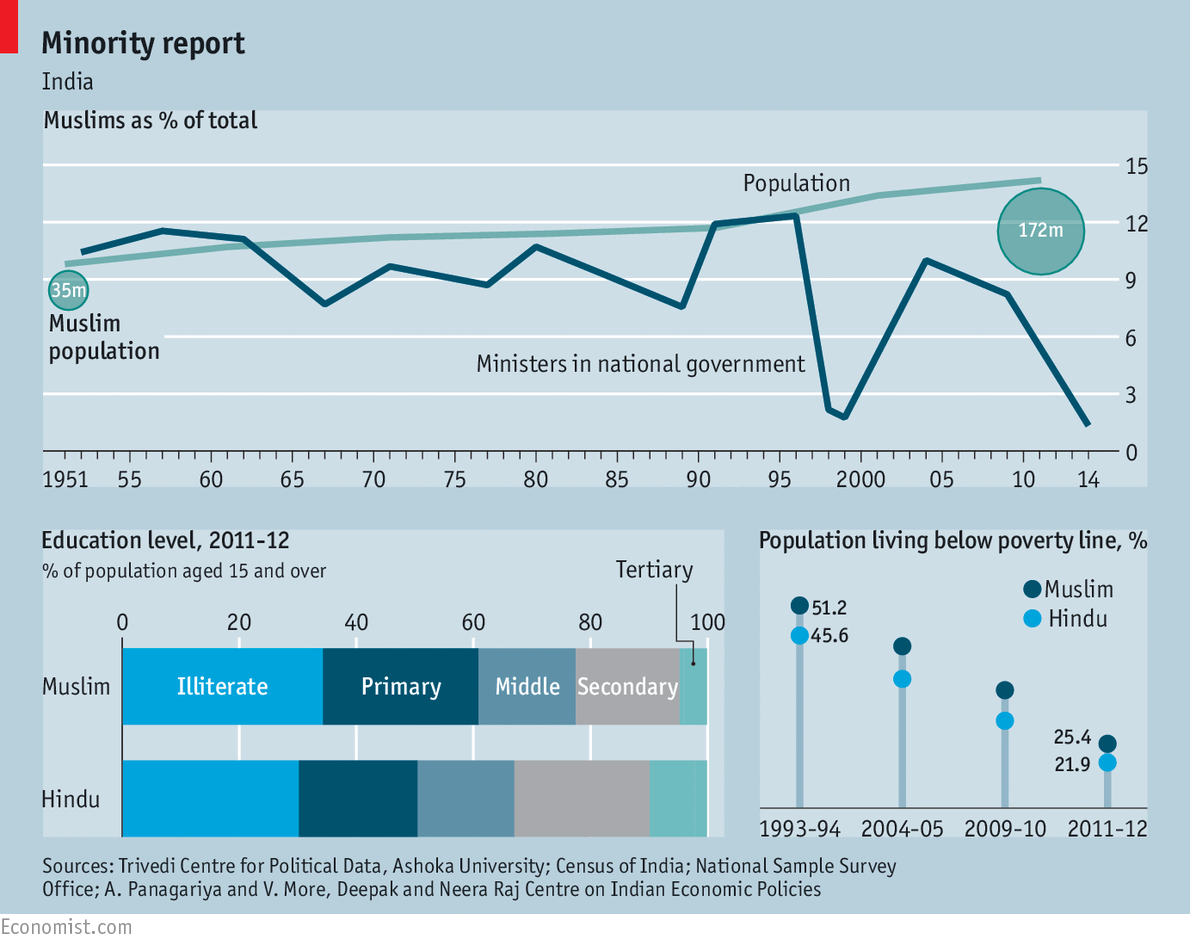

FOR a community of 172m, almost 15% of the population, Muslims at first glance appear oddly absent from the pages of India’s newspapers. In fact, they crop up a lot, but not by name. Instead, reporters coyly refer to “a certain community”. The clumsy circumlocution is a way of avoiding any hint of stoking sectarian unrest. The aim is understandable in a country that was born amid ferocious communal clashes and which has suffered all too many reprises. But the dainty phrase also hints at something else. Since India’s independence in 1947, the estrangement of Muslims has slowly grown.

India’s Muslims have not, it is true, been officially persecuted, hounded into exile or systematically targeted by terrorists, as have minorities in other parts of the subcontinent, such as the Ahmadi sect in Pakistan. But although violence against them has been only sporadic, they have struggled in other ways. In 2006 a hefty report detailed Muslims’ growing disadvantages. It found that very few army officers were Muslim; their share in the higher ranks of the police was “minuscule”. Muslims were in general poorer, more prone to sex discrimination and less literate than the general population (see chart). At postgraduate level in elite universities, Muslims were a scant 2% of students.

A decade later, with most of the committee’s recommendations quietly shelved, those numbers are unlikely to have improved. Indeed, since the landslide election win by the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 2014, some gaps have widened. There are fewer Muslim ministers now in the national government—just two out of 75—than at any time since independence, even though the Muslim share of the population has grown.

India remains a secular country, yet some laws proposed by the BJP bear a disturbingly sectarian tint. One bill would allow immigrants from nearby countries who happen to be Hindu, Sikh, Christian or Buddhist to apply for citizenship, while specifically barring Muslims. Another would retroactively block any legal challenge to past seizures of property from people deemed Pakistani “enemies”, even if their descendants have nothing to do with Pakistan and are Indian citizens. Courts have repeatedly ruled in favour of such claimants—all of them Muslim—but their families could now be stripped of any rights in perpetuity.

Far more than such legislative slights, what frightens ordinary Muslims is the government’s silence in the face of starker assaults. A year ago many were shocked when a mob in a village near Delhi, the capital, beat to death a Muslim father of three on mere suspicion that he had eaten beef. Earlier this month, after one of his alleged killers died of disease while in police custody, a BJP minister attended the suspect’s funeral, at which the casket was draped, like a hero’s, with the Indian flag.

Earlier this month, too, newspapers reported a disturbing discrepancy between the fates of two men arrested for allegedly spreading religiously insulting material via social media. One of the men, a member of a right-wing Hindu group in the BJP-run state of Madhya Pradesh, was quickly released from custody after the customary beating. The arresting officers have been charged with assault; their superiors up to the district level transferred. In the other case, in the state of Jharkhand, a Muslim villager was arrested for posting pictures implying he had slaughtered a cow. Police claimed he died of encephalitis following his arrest. A court-ordered autopsy revealed he had been beaten to death. To date, no police officers have been charged.

The BJP’s handling of a popular uprising in India’s only Muslim-majority state, Jammu and Kashmir, has also raised Muslim concern. Four months into the unrest, in which dozens of civilians have been killed and hundreds injured, with continuous curfews and strikes keeping schools and shops closed, the government still refuses to talk to any but the most supine local politicians. “You don’t understand,” snaps a cabinet minister, “It’s a violent movement to build an Islamic theocracy. No democracy can tolerate that.”

Omair Ahmad, a writer on Muslim affairs, scoffs at this. The problem, he says, is that Indian governments insist on treating Kashmir as a “Muslim issue” when the real question is one of democratic representation. Yet most Indian Muslims tend to toe the official line, either from a desire to appear loyal or because they genuinely feel only a faint bond with Kashmir.

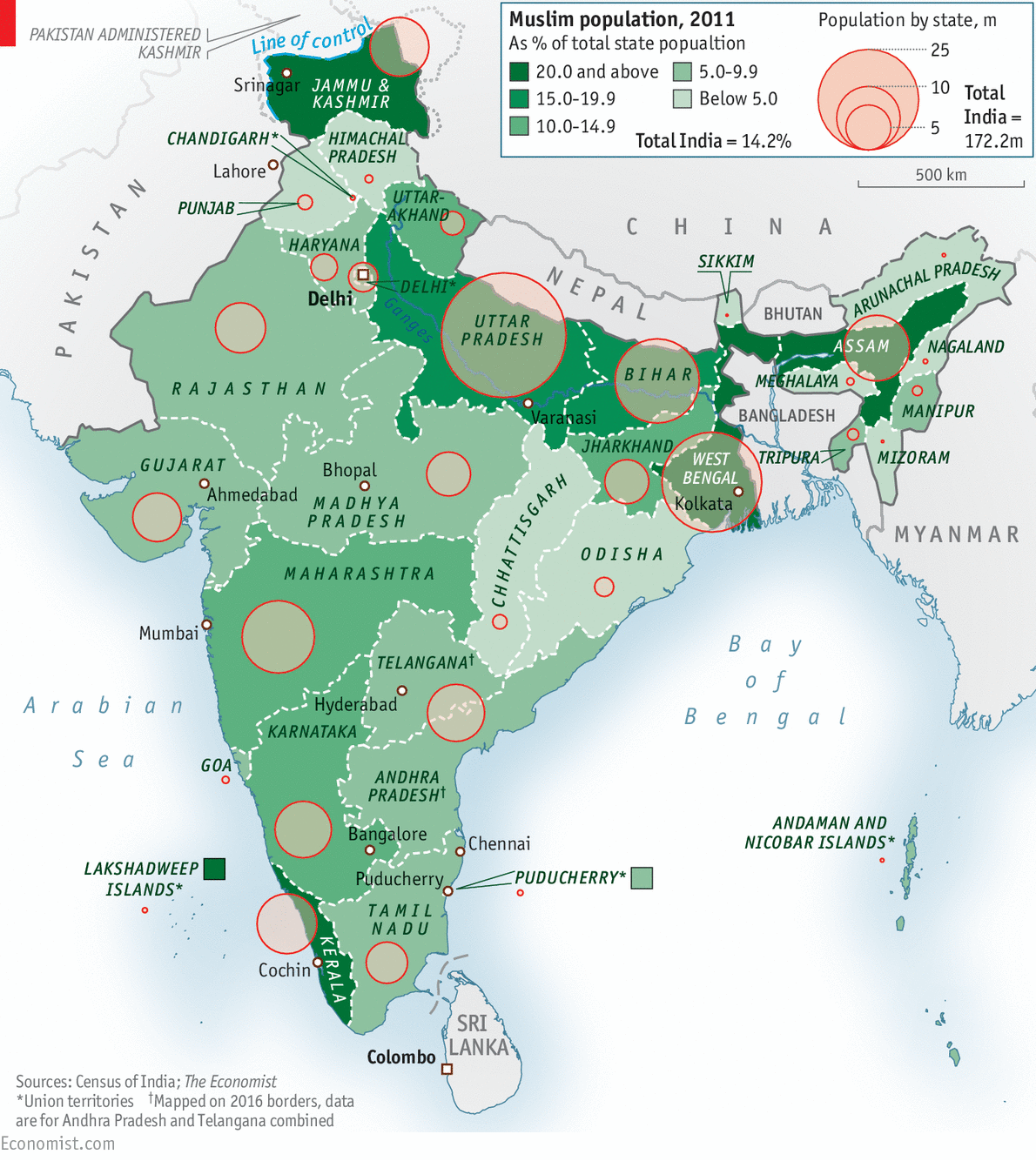

The fact is that India’s Muslims are divided, not only between dominant Sunnis and a large Shia minority but also between starkly different social classes and regions: a Muslim in Bengal is likely to share no language and few traditions with a co-religionist far to the south in steamy Kerala. The divisions may soon get deeper. Both India’s supreme court and the national law commission, a state body charged with legal reform, are deliberating whether laws governing such things as divorce and inheritance should remain different for different religious groups, or should be harmonised in a uniform national code, as the constitution urges. Spotting another “Muslim issue”, past governments have let conservative clerics control family law. As a result India, unlike most Muslim-majority countries, still allows men to divorce simply by pronouncing the word three times.

The BJP, however, is calling for sweeping reform, with Narendra Modi, the prime minister, painting the issue as a straightforward question of women’s rights. Much as many Muslims heartily agree that change is long overdue, suspicions linger that the BJP’s aim is less to generate reform than to spark inevitable protests by Muslim conservatives, so uniting Hindus in opposition to Muslim “backwardness”.

This question may play out in elections this winter in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, nearly 40m of whose 200m people are Muslim. The state has witnessed repeated communal clashes since the destruction by Hindu activists, in 1992, of a medieval mosque said to have been built over an ancient temple marking the birthplace of Rama, a Hindu deity. Many expect the BJP to play the “Muslim card” in an effort to rally Hindu votes.

There is hope: a similar ploy flopped last year in the neighbouring state of Bihar. Whatever the outcome, India’s Muslims feel increasingly like spectators in their own land. “They called it a secular state, which is why many who had a choice at partition wanted to stay here,” says Saeed Naqvi, a journalist whose recent book, “Being the Other”, chronicles the growing alienation of India’s Muslims. “But what really happened was that we seamlessly glided from British Raj to Hindu Raj.”

Source: The Economist