A 1958 Pakistani film, considered by critics as the best ever made in the country and boasting a curious collaboration with India, is haunted by its spectacularly jinxed past more than half-a-century later, writes Faizal Khan.

At the 69th Cannes film festival last month, a feature film from Pakistan made a rare appearance in a segment dedicated to airing restored movies.

The Urdu language film Jago Hua Savera, which means The Day Shall Dawn, was screened along with classics such as Russian maestro Andrei Tarkovski’s Solaris, French director Regis Wargnier’s Indochine and Egyptian auteur Youssef Chahine’s Goodbye Bonaparte at the festival, which was held from 11-22 May.

Set in the 1950s in a fishing village, Jago Hua Savera carries a lot of historical baggage.

When director Aaejay Kardar began making the movie in 1958, the political landscape of Pakistan had just begun to change.

‘Branded Communists’

General Ayub Khan had become the first military dictator of the country in a coup only months earlier, positioning the country firmly in the American camp during the Cold War.

“Three days before the release of the film, the government asked my father not to go ahead with it,” Anjum Taseer, son of producer Nauman Taseer, told the BBC at the screening of the film.

“The government branded the young artists and writers involved in the making of the film as Communists.”

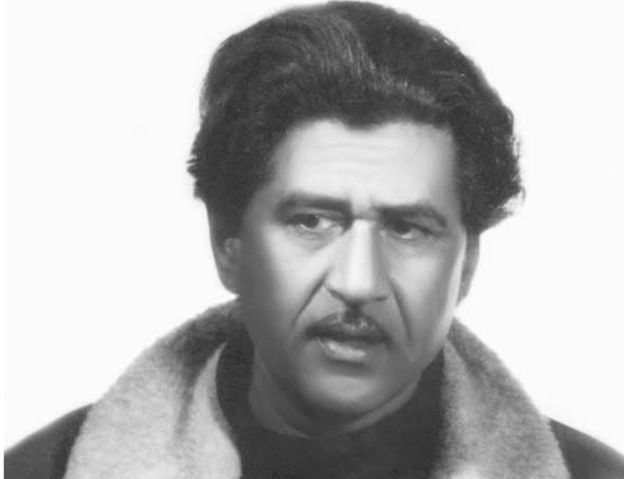

It did not help that iconic poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, who was a known revolutionary, had written the script, lyrics and dialogue of the film.

“Gen Ayub Khan imprisoned my father and many other artists,” said Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s daughter Salima Hashmi.

It was decided to premiere the film in London, but the military government instructed the Pakistan high commission to boycott the event.

“But on that day, then high commissioner and his wife defied the order,” Mr Taseer said.

Unusual collaboration

Inspired by the early works of iconic Indian director Satyajit Ray, Jago Hua Savera is moulded in neo-realism, a genre shaped by Italian greats like Luchino Visconti and Vittorio De Sica.

Shot in black and white on location on the banks of the majestic Meghna river in Bangladesh, then East Pakistan, the film portrays the hardships of a fishing community in Saitnol village near Dhaka, which is at the mercy of loan sharks.

It presents an unusual collaboration between Pakistani and Indian professionals, only a decade after the bloody partition.

Faiz’s script was inspired by a story written by popular Bengali author Manik Bandopadhyay. Towering Indian musician Timir Baran, who lived in Kolkata (Calcutta), provided the music.

Watershed cinema

Bengali actor Tripti Mitra and her husband Sombhu Mitra were both members of the Left-leaning Indian People’s Theatre Association of the 1940s. With Faiz, Baran and Mitra on board, the producer commissioned British cinematographer Walter Lasally, who later won an Oscar for his work on Zorba the Greek.

“The film is a watershed in the history of Pakistani cinema,” says Indian film critic Saibal Chatterjee. “It is the only neo-realism film we know of, from the country. It was lost and those who restored it have done a great job in rediscovering the film.”

Given its high aesthetic and production quality and all the publicity it received due to the controversy with the government, Jago Hua Savera should have been a runaway success, but that was not to be.

Within weeks, everybody, including its makers, forgot about the film. A classic that belonged alongside films like La Strada, The Bicycle Thief and Pather Panchali was instead lost to the world of cinema.

Nobody talked about it for another 50 years until two French brothers Philippe and Alain Jalladeau, founders of the Three Continents Film Festival in Nantes, France, decided to screen a retrospective of Pakistani films in 2007.

Race against time

“It was then that Shireen Pasha (Pakistani documentary filmmaker and head of the department of film at the National College of Arts, Lahore) said you can’t have a retrospective of Pakistani films without Jago Hua Zavera,” says Philippe Jalladeau.

What followed was a frantic search for a print of the film that took Taseer (his father died in 1996) across Pakistan and Bangladesh, and film archives in the western Indian city of Pune, London and Paris.

One week before the festival, Taseer found some reels of the film with a French distributor, some in London and the rest in Karachi, eventually putting them together for a “showable print”.

After the Nantes festival, Taseer took on the task of properly restoring the film and sent a copy to a lab in the Indian city of Chennai. “It took six months to get the copy released by the Indian customs,” says Taseer, who then, exasperated by the delay, decided to take the film to London for restoration in 2008 instead. It was finally completed in 2010.

On an unusually warm Sunday morning on 15 May, Taseer joined Faiz’s daughter Hashmi and Philippe Jalladeau to present the film in the Bunuel theatre, at the Palais des Festivals venue of Cannes.

Continuing journey

The hall was half empty – there were no Pakistani film critics, and only four Indian journalists were present.

But Taseer’s and the film’s journey are not over. He is aware of the generation gap between the film and today’s audience, but is not ready to give up yet.

“I want to show the film in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh,” he told the BBC. “The

film is a combination of the efforts of the people of the three countries.”

He is also aware that the lives of the fishing communities in the three countries have not changed much.

“The fishermen of today have mobile phones, but the same loans,” he said.

“There are several young and talented people in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. I want to produce a film on the lives of these fishermen with the help of these talented filmmakers.”