The March 2012 decision of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in the long-standing Bangladesh/Myanmar maritime border dispute opened up new possibilities for peaceful resolution of such disputes in Asia. While the judgment itself broke important—if technical—legal ground, the two parties’ incentives for entering into litigation in the first place offer equally valuable lessons for future disputes.

Bangladesh and Myanmar were driven to seek the tribunal’s opinion because both realized that continued uncertainty over their maritime boundary was worse than almost any award the judges might realistically grant. The undefined status of the continental shelf in the northeastern Bay of Bengal was scaring away international investors and energy companies who would otherwise have jumped at the chance to explore potentially vast new natural gas fields. The dispute cast a pall over the whole region; energy companies were reluctant to invest even in areas far from the disputed waters. And since any ruling was likely to leave each country with some of the area believed to hold gas deposits, both were able to accept the risk of submitting to a neutral arbiter.

This is a reminder of the rather obvious—it is easier to convince both parties in a dispute to submit to third-party resolution when the result is likely to objectively benefit both. The tribunal’s judgment was accepted with some degree of warmth by both sides (each of whom could plausibly claim that it had “won” the case). Even more importantly, the decision has stuck; the two states have not returned to conflict and have instead been competing to offer the most favorable terms to international energy companies interested in natural gas deposits in the Bay of Bengal.

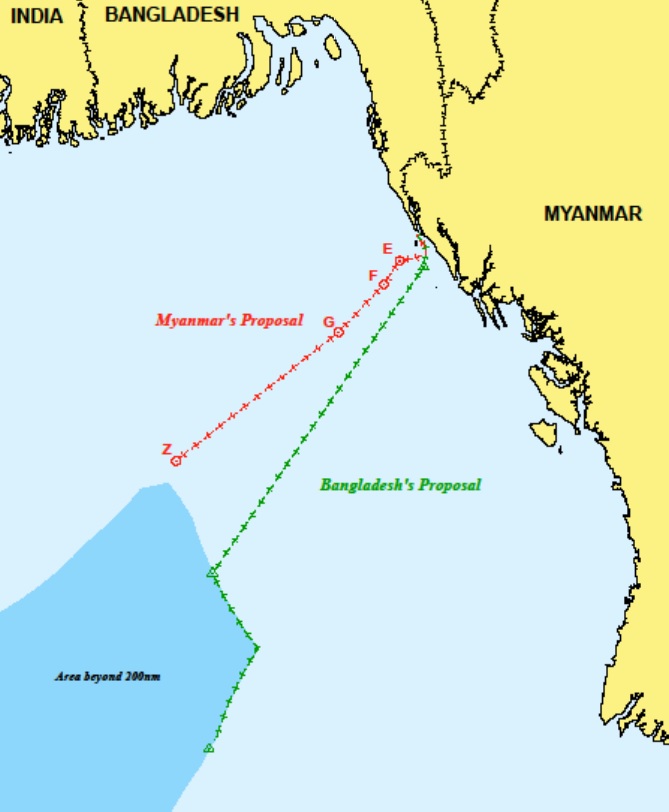

The case had its origins equally in law and politics. Bangladesh’s long, concave coastline makes maritime boundary disputes almost inevitable. Under a standard application of maritime boundary law, the intersecting arcs of India’s and Myanmar’s 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) would cut off Bangladesh’s access to the continental shelf and leave it with a disproportionately small EEZ relative to the length of its coastline. As a result Myanmar and Bangladesh made competing claims to a section of ocean and seabed extending southwest in a widening sliver from the seaward terminus of their land border.

Sketch map composed by ITLOS illustrating the competing claims of Bangladesh (green) and Myanmar (red).

The two countries had irreconcilable views of their respective maritime boundaries but the dispute largely remained on the back burner until late 2008, when South Korea’s Daewoo, at the behest of Myanmar, began natural gas exploration in waters claimed by Bangladesh. A few weeks later, Bangladesh submitted its continental shelf claim to the United Nations’ Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. The public declaration was a stark reminder of Bangladesh’s and Myanmar’s conflicting claims in the area. Both countries mobilized naval forces in the disputed area and the conflict narrowly escaped escalation.

ITLOS had never before ruled on a maritime boundary dispute and its perceived neutrality and status as a blank slate increased the two countries’ willingness to submit the case to the tribunal. As the National Bureau for Asian Research’s Jared Bissinger makes clear, Bangladesh hoped that considerations of equity would persuade the court to employ relatively untested methods of boundary delimitation. Myanmar, for its part, was confident that the application of the traditional principle of equidistance would lead to a favorable result, and that the court would avoid ruling on the issue of the continental shelf and focus solely on dividing up waters within 200 nautical miles of shore. Thus both sides believed they had a winning case—a strong incentive to seek legal redress.

In the end the tribunal chose, quite literally, a middle path. It modified the boundary that would have resulted from the equidistance approach (which sets the maritime boundary between two states by drawing a line equidistant from a series of “base points” on each state’s coastline) in order to avoid cutting off Bangladesh from the outer reaches of its EEZ. The resulting line was almost exactly in the center of the boundaries proposed by Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The ruling was noteworthy in part for the court’s decision that it had jurisdiction to decide not only competing claims to waters but also the continental shelf, and for the creation of a “grey area” that is on Bangladesh’s side of the boundary line drawn by the court but within the potential 200-nautical-mile EEZ of Myanmar. In this grey area, Bangladesh controls the seabed but Myanmar the superjacent waters. Similar grey areas have since been created by other bodies, including in the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s July 2014 ruling on the India/Bangladesh boundary dispute. The grey area is the result of the tribunal’s concern for an equitable resolution of the dispute. In this case, allowing Myanmar to claim the seabed in the grey area—to which it would normally be entitled—would cut Bangladesh off from a much larger section of its own continental shelf.

Sketch map composed by ITLOS illustrating the “grey area” in which Bangladesh has jurisdiction over the seabed but Myanmar’s has jurisdiction over the water.

Equally important was the court’s treatment of St. Martin’s Island, a small island belonging to Bangladesh but located directly west of Myanmar. The Tribunal gave full effect to the island when delimiting the two countries’ territorial seas, but did not allow Bangladesh to use the island as a base point when marking the equidistance line between the two states’ EEZs and continental shelves. The decision also minimized the island’s importance by declining to identify it as a “relevant circumstance” that should be considered when making adjustments to the boundary line.

The treatment of St. Martin’s island came in for strong criticism in the separate opinion of Judge Zhiguo Gao, China’s appointee on the tribunal, who described the decision to give full effect to the island in delimiting the territorial seas but to ignore it in delimiting the EEZ and continental shelf boundaries as “wrong and unacceptable.” Gao argued that the result was unfair to Bangladesh and that the island should be given half effect in delimiting the larger maritime boundary. In his dissenting opinion, he gave special weight to the island’s degree of economic development, the size of its population, and its closeness to the mainland—implying that in his view not all islands are created equal for maritime boundary delimitation purposes. This debate over St. Martin’s has far reaching implications for small islands in disputed waters elsewhere in Asia.

Sketch map composed by ITLOS showing St. Martin’s Island’s effect on the drawing of a territorial sea boundary between Myanmar and Bangladesh. The tribunal gave the island no effect on the EEZ and continental shelf boundary.

Unfortunately the tribunal’s success in attracting this relatively low-stakes case might actually diminish larger powers’ willingness to submit to its judgment. ITLOS is no longer a blank slate onto which both parties can project their hoped-for outcomes. Its decisions on maritime boundary disputes, together with those of other bodies, are evolving into an established body of jurisprudence on the subject. Parties to disputes increasingly have at least a general idea of what the outcome of their case might be, and they are unlikely to enter into litigation if they might not like the result.

Sarah Watson is an Associate Fellow in the Wadhwani Chair for U.S.-India Policy Studies at CSIS. She holds a JD from Yale Law School and a Masters in Security Studies from Georgetown University.