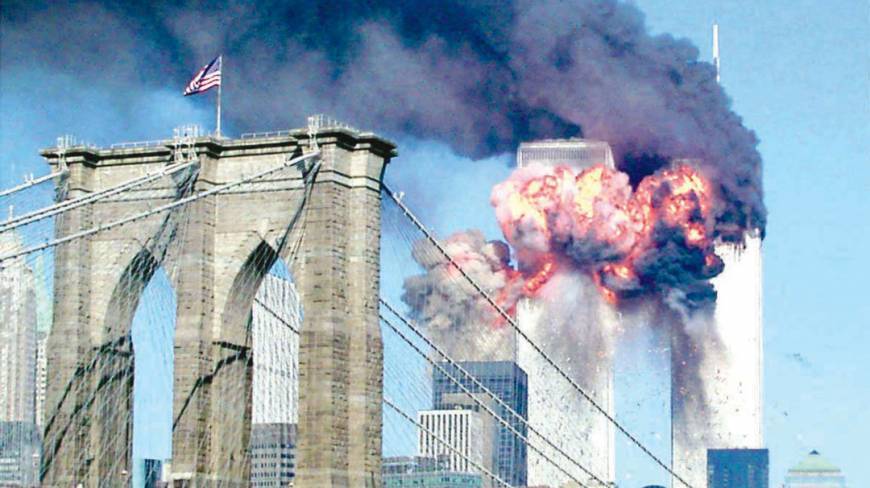

The US government is considering declassifying a controversial 28-page section of a congressional report on 9/11. Here’s everything you need to know:

Why is it controversial?

Those pages concern whether or not Saudi Arabian officials were involved in funding or supporting the hijackers. In 2002, the bipartisan Joint Congressional Inquiry conducted an extensive investigation into the intelligence failures in the lead-up to 9/11. President George W Bush sealed the section covering Saudi Arabia’s possible involvement, presumably to avoid damaging relations with one of America’s closest Middle Eastern allies. Since then, the 28 pages have been locked in a basement room at the US Capitol; lawmakers can read them, but are forbidden from revealing their exact contents. Spearheading the campaign to have them declassified is former Senator Bob Graham, who co-chaired the inquiry. “The 28 pages primarily relate to who financed 9/11,” he said last year, “and they point a very strong finger at Saudi Arabia.”

Why are the pages still sealed?

The official rationale is that they identify people whose alleged complicity was never proved. The 9/11 Commission followed up on the original inquiry, and concluded in 2004 that there was “no evidence” the Saudi government or senior Saudi officials aided al Qaeda in the run-up to the attacks, even though 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudis. Last year, an internal CIA investigation came to the same conclusion. Yet neither report ruled out the possibility that lower-level government officials were involved. John Lehman, a former Navy secretary under President Reagan who served on the 9/11 Commission, said the report found evidence that at least five Saudi officials helped the hijackers. “There was an awful lot of participation by Saudi individuals in supporting the hijackers, and some of those people worked in the Saudi government,” he said. “Our report should never have been read as an exoneration of Saudi Arabia.”

So what do we know?

It is well established that Saudi Arabia’s royal family, the House of Saud, had very close ties to President Bush and his father, President George H W Bush. Saudi investment firms poured money into Bush Sr’s oil business, and the country provided the US with invaluable support in the first Gulf War. Two days after 9/11, Saudi Arabia’s influential ambassador to Washington, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, met with President Bush at the White House, and the two men smoked cigars on the Truman Balcony. Over the next few days, the Saudis were allowed to collect more than 160 Saudi officials — including relatives of Osama bin Laden — from around the US and fly them on chartered jets to Saudi Arabia. Some even received an FBI escort to the airport.

What about before the attacks?

Much of the focus has been on Omar al-Bayoumi, who the FBI suspected was a Saudi intelligence officer. When two of the hijackers arrived in Los Angeles in January 2000, al-Bayoumi met them in a restaurant, took them to San Diego, and set them up in an apartment, co-signing the lease and advancing them $1,500 for rent. He later helped the pair — who spoke almost no English — find a flight school. Al-Bayoumi insisted the restaurant meeting was a chance encounter, and that he was just helping out fellow Muslims. But he was also in regular contact with Fahad al-Thumairy, a Saudi consulate official who was deported in 2003 for suspected terrorist links, and with Anwar al-Awlaki, the radical, American-born Islamic preacher who helped inspire several terrorist attacks. Al-Bayoumi was questioned by the FBI, but released without charge.

Is there any other evidence of complicity?

During 2000 and 2001, al-Bayoumi received about $3,000 a month — through several intermediaries — from Prince Bandar’s wife. Many suspect some of this cash was passed on to the hijackers. Bandar has also been accused by Zacarias Moussaoui, the so-called 20th hijacker, of being one of al Qaeda’s donors in the run-up to the attacks. The Saudi government says Moussaoui is mentally ill and unreliable, vehemently denies that it had any involvement in 9/11, and has even called on the US government to release the notorious 28 pages. “Saudi Arabia has nothing to hide,” Bandar said in 2003. “We can deal with questions in public, but we cannot respond to blank pages.”

Why is this coming up now?

Congress is considering a bill that would allow US citizens to sue Saudi Arabia for its alleged support of the hijackers. Foreign governments currently receive immunity from prosecution in the US, but the new legislation — which was passed unanimously by the Senate — would grant exceptions when countries are found culpable of involvement in terrorist attacks. Saudi Arabia has threatened to sell $750bn of US-based assets if the bill is enacted. Many members of Congress argue that releasing the 2002 Joint Congressional Inquiry’s findings in full would shed light on whether the Saudis have some specific allegations to answer. “[There] are a lot of coincidences,” says former Rep. Tim Roemer. “Is that enough to make you squirm and [feel] uncomfortable, and dig harder, and declassify these 28 pages? Absolutely.”

How Bandar Bush helped the home team

At the heart of the close relationship between the US and Saudi Arabia on 9/11 was one man: Prince Bandar. A grandson of the Gulf state’s founding king, Bandar was the Saudi ambassador to the US from 1983 to 2005, and went on to run his country’s intelligence agency. He was so close to the Bushes he was often called “Bandar Bush,” and he was instrumental in persuading his government to assist the US in the first Gulf War. In 2003, he was briefed by Bush Junior on the plan to invade Iraq — two days before Vice President Dick Cheney or Secretary of State Colin Powell. In Washington, Bandar was a master of diplomacy. His opulent parties were legendary — his other nickname was “the Arab Gatsby” — and he cultivated relationships with the administration’s most powerful figures. Shortly after Powell resigned in 2005, for example, Bandar presented him with a 1995 Jaguar — a car Powell’s wife had once mentioned in passing that she liked. But there was never any doubt over whose side Bandar was on. “Don’t expect the man not to play the game for his home team,” says William Simpson, Bandar’s biographer. “The home team is Saudi Arabia.”

Source: Dhaka Tribune