Rumi Ahmed

By any standard, the Republic of South Africa stands as the continent’s most enduring and resilient democracy.

Yet, this achievement was neither inevitable nor easily foreseen. The waning years of the apartheid regime were marked by unspeakable violence and bloodshed.

Between 1990 and 1994, as the government cracked down on the African National Congress (ANC) and other resistance movements, an estimated 14,000 lives were lost amid political strife and tribal conflict.

Amid this turmoil, a moment of extraordinary transformation arrived.

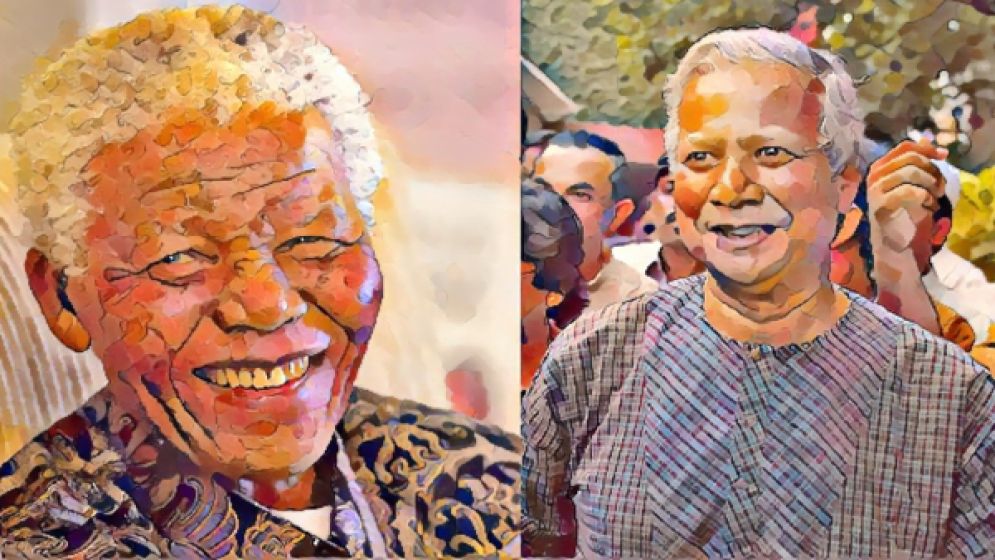

Nelson Mandela, long a symbol of resistance and largely unknown to many after 27 years of imprisonment, emerged to lead South Africa’s first democratic election.

For the first time in history, black South Africans were granted the right to vote, and under Mandela’s leadership, the country was ushered into a new era—a native black government was born.

The world watched, gripped with anxiety, bracing for the collapse of the new democracy. Pundits and analysts warned of a descent into violence and chaos.

But against all odds, South Africa not only survived; it reconciled, stabilized, and prospered.

The key to this remarkable turnaround was Mandela’s visionary leadership—his unwavering commitment to reconciliation.

Mandela’s approach defied expectations. In his first post-apartheid government, he appointed F.W. de Klerk, the last president of the apartheid regime, as Deputy President.

He retained Derek Keys as Finance Minister, appointed Roelf Meyer, a leading negotiator for the apartheid regime, as Minister of Constitutional Affairs, and brought back Pik Botha, the apartheid regime’s longest-serving Foreign Minister.

These choices were emblematic of Mandela’s commitment to inclusivity, forging a government that sought unity rather than division.

Perhaps Mandela’s most profound contribution was his establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a bold initiative to heal the wounds of a nation scarred by decades of injustice.

This act of statesmanship ensured that South Africa avoided the civil war that many feared and gave the new democracy the foundation it needed to thrive.

Three decades later, South Africa’s democratic project remains intact. The country’s political stability and commitment to human rights are remarkable in the face of its troubled history.

Mandela’s legacy is not merely symbolic—it is the bedrock on which South Africa’s enduring democracy was built.

Lessons from South Africa for Bangladesh

South Africa’s transition from apartheid offers a compelling lesson for Bangladesh. When Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman faced the monumental task of building a new state.

His response was to form a government exclusively composed of his party members. In retrospect, a more prudent approach may have been the formation of a government of national unity, one that incorporated individuals with experience from the previous Pakistani administration or even those opposed to Bangladesh’s independence.

A process of truth and reconciliation could have facilitated this, reserving justice for those accused of war crimes while offering rehabilitation to others, allowing them to contribute to the fledgling state.

Regrettably, this path was not taken, and the result was a nation plunged into political and economic turmoil, culminating in the bloody coups of 1975.

It was only with the leadership of President Ziaur Rahman in the mid-1970s that Bangladesh began to regain its footing.

Zia, adopting a reconciliatory approach, sought to reintegrate experienced but sidelined bureaucrats like S.M. Shafiul Azam.

Despite fierce criticism, he also rehabilitated former supporters of a unified Pakistan in order to stabilize the administration.

His statesmanship, much like Nelson Mandela’s, helped avert further chaos and steered Bangladesh toward recovery.

The disastrous outcome of post-Gulf War Iraq serves as another stark reminder of the dangers of exclusion.

The U.S.-led dismantling of Saddam Hussein’s regime created a power vacuum that fueled sectarian violence and destabilized the country for decades.

This, along with other global examples, underscores the importance of reconciliation and inclusivity in nation-building.

Whether rebuilding a fractured South Africa or attempting to stabilize a post-war Iraq, the lesson is clear: exclusionary policies inevitably lead to long-term instability.

Bangladesh at a Crossroads

Bangladesh now finds itself at a critical crossroads.

After 16 years of authoritarian rule, the country’s core institutions—its civil administration, military, education system, and financial structures—are in disarray.

Human development has stalled across multiple sectors. The interim government, under the leadership of Professor Muhammad Yunus, now faces a monumental task: to reform the state, oversee a peaceful transition to a democratically elected government, and, perhaps most urgently, heal a deeply fractured society.

Reconciliation will be at the heart of this challenge. The interim government must summon the courage to hold those responsible for state-sponsored crimes and corruption accountable, while also reintegrating individuals who were previously marginalized but were forced to collaborate with prior regimes.

This means rebuilding vital institutions and bridging the deep divides within society.

Such a strategy will undoubtedly provoke backlash, but history teaches us that true leadership often requires boldness and the willingness to risk personal reproach for the greater good.

Nelson Mandela’s leadership in South Africa demonstrated that inclusivity and reconciliation can heal even the most divided societies.

Similarly, Ziaur Rahman’s approach in Bangladesh showed that rehabilitating sidelined individuals can stabilize a fragile state.

Both leaders faced intense criticism for their decisions, but both ultimately succeeded in averting chaos and laying the groundwork for a more promising future.

The question today is whether Professor Muhammad Yunus can rise to meet this challenge.

Can the Nobel laureate transform from a renowned philanthropist into the reformer and statesman Bangladesh urgently needs?

History will judge him not by the obstacles he faces, but by the legacy he leaves behind. This moment demands not only courage and vision but also the audacity to unite a fractured nation.

Professor Yunus stands at a crossroads, much like Zia did in 1975 or Mandela in 1994.

The choices he makes in the coming months could shape the trajectory of Bangladesh for generations.

If he can draw from the lessons of Mandela and Zia—prioritizing reconciliation, inclusivity, and institutional reform—he has the potential to restore stability and redefine the nation’s future.

As history has shown, great leaders emerge in times of crisis, willing to take risks for the common good.

Whether Professor Yunus will seize this opportunity remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that the path forward demands boldness, vision, and the willingness to embrace all corners of society in order to forge a unified and prosperous future.

Bangla outlook