Myanmar goes to the polls on Sunday, taking its biggest stride yet in a journey to democracy from dictatorship, but the legacy of military rule means opposition icon Aung San Suu Kyi cannot become president even if her party wins a landslide.

The sense of excitement in the Southeast Asian nation was palpable on the eve of the election as around 30 million people prepared to vote in the first free nationwide poll in a quarter of a century.

“I really want change,” said Zobai, a Muslim jade trader in the second-largest city of Mandalay who goes by one name. “I’ve been alive for 53 years and all I’ve seen is dictatorship.”

Religious tensions marred the run-up to the election, fanned by Buddhist nationalists whose actions have intimidated Myanmar’s Muslim minority.

Nobel peace laureate Suu Kyi won the last free vote in 1990, but the military ignored the result. She spent most of the next 20 years under house arrest before her release in 2010.

Her National League for Democracy (NLD) is expected to win again, but she is barred from taking the presidency herself under a constitution written by the junta to preserve its power.

If she wins a majority and is able to form Myanmar’s first democratically elected government since the 1960s, Suu Kyi says she will be the power behind the new president regardless of a constitution she has derided as “very silly”.

Muslim men leave a mosque after prayers ahead of tomorrow’s general election in Mandalay, Myanmar, November 7, 2015. Reuters

Women look at names on a list outside a polling station ahead of tomorrow’s general election in Mandalay, Myanmar, November 7, 2015. Reuters

Suu Kyi starts the contest with a sizeable handicap in parliament: even if the vote is deemed free and fair, one-quarter of parliament’s seats will still be held by unelected military officers.

To form a government and choose its own president, the NLD on its own or with allies must win more than two-thirds of all seats up for grabs.

By contrast, the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) would need far fewer seats if it secured the backing of the military bloc in parliament.

However, voters are expected to spurn the USDP, created by the former junta and led by former military officers, because it is associated with the brutal dictatorship that installed President Thein Sein’s nominally civilian government in 2011.

An inconclusive result could thrust parties representing Myanmar’s myriad ethnic minorities into a king-maker role, bringing them closer to the centre of power after years on the fringes.

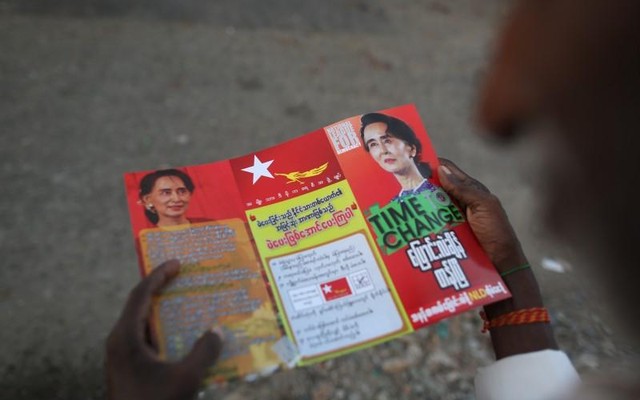

‘Time for change’

In Mandalay, a hotbed of Buddhist nationalism, men streaming out of the Joon Mosque on Saturdayexpressed admiration for Suu Kyi – but also apprehension about post-election politics.

“I feel like a student waiting for his exam results. I’m afraid we might lose,” said Alaslam, 60, in the mosque’s tiled courtyard.

Zobai, the jade trader, blamed the government and military for stoking anti-Muslim hatred in the majority Buddhist country, most recently via anonymous flyers and banners that said an NLD win would pave the way to a Muslim takeover of the country.

Volunteers work in a polling station for Rohingya Muslims minority who have citizen cards near a refugee camp outside Sitttwe, Rakhine state November 7, 2015. Reuters

Women label ballots at a polling station ahead of tomorrow’s general election in Mandalay, Myanmar, November 7, 2015. Reuters

Until just a few years ago a pariah state, Myanmar has little experience organising elections.

Underlining the infancy of its democracy, a survey released on Saturday by the Mizzima media group showed that just 29 percent of voters were familiar with the candidates in their areas.

More worrying is the prospect of an unfair vote after it emerged that around 4 million people will be unable to cast a vote.

Thousands are missing from voter lists, millions abroad failed to register in time, and most of the 1.1 million persecuted Muslim Rohingya minority are barred from voting.

In a pre-election speech on Friday, President Thein Sein acknowledged that organising the vote was a challenge and stressed the government’s commitment to ensuring a credible vote, with more than 10,000 observers scrutinising the process.

“People are really interested in the election and eager to vote,” said Hla Myo, a poll volunteer in the country’s largest city, Yangon.

A polling station is ready for voting inside a school before Myanmar’s general election in Yangon November 7, 2015. Myanmar heads to the polls on Nov. 8. Reuters

He said more “advance voting” forms had to be ordered at the last minute for people who would be unable to cast their ballots on the day.

Security has been tightened around the country, with 40,000 specially trained police dispatched to polling stations, and some Yangon restaurants and markets have been closed.

The president sought to dispel concern that the military or the government would reject the vote.

“I’d like to say again that the government and the military will respect and accept the results,” he said. “I will accept the new government formed, based on the election result.”

Source: bdnews24