by R Chowdhury 22 October 2023

Which nation? Has anyone ever heard Sheikh Mujibur Rahman ever uttering the term “Independent East Pakistan/Bangladesh” before 1971? Not that I know of. The closest he came to independence was on March 7, 1971 when he said, “এবারের সংগ্রাম, স্বাধীনতার সংগ্রাম …the struggle this time is for independence…” It was not a call for independence.

The only person who repeatedly spoke about independence since 1957 was Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani. Even Sher-e-Bangla A K Fazlul Haq lost his job as Chief Minister in 1954 when he notified the center that his ultimate goal was an independent East Pakistan.

There was no evidence that Sheikh Mujib ever wanted an independent Bangladesh. His lifelong political struggle was East Pakistan’s provincial autonomy, which was shaped into Six Points in 1966. He fought the election in 1970 under President General Yahya Khan’s Legal Framework Orders (LFO) that categorically emphasized the unity of Pakistan. Even after his March 7 call, Mujib kept negotiating with the central leaders (March 15-25) to craft the future of Pakistan, not Bangladesh.

Surrender

When the Pakistan military commenced its genocide on the unarmed Bengalis on the night of March 25, he declined the repeated requests of his deputy Tajuddin Ahmad and others to declare independence and join the war of liberation (Ref: Tajuddin Ahmad Neta O Pita by Sharmin Ahmad). To the contrary, he quietly negotiated with president Yahya to surrender in exchange of befitting hospitality for himself and his family (Ref: Witness to Surrender by Siddiq Saleq). He had no consideration for the 70 million Bengalis who called him “Bangabandhu” and reposed their full trust in him. They were left to be massacred by the Pakistan military. Zoglul Husain, winner of the Freedom Award and a prominent political analyst, calls Mujib and his family as the betrayers of the nation and the first collaborators with Pakistan.

Viewers Reaction

I haven’t had the opportunity to see the biopic titled Mujib: The Making of a Nation (মুজিব: একটি জাতির রূপকার), which has been released on October 13 under official sponsorship and with much fanfare in Bangladesh. I could only watch a trailer that was released to the public. However, I read a few viewer fractions, both positive and negative. Positive by those who either belonged to a self-serving clan that saw Mujib as a “god,” and those consumed or indoctrinated by the Awami script strictly following the dictates of Sheikh Hasina, daughter of Mujib. Negative by those who either knew the real Mujib or found plenty of missing links, and irrelevant and untrue facts.

One young man questioned, after observing tears in a few watchers in the movie hall, “Where were all these tears on August 15? Why did nobody protest the killing of Mujib that day? Why was no person available for his Janaza, final rites? Instead, sweets were distributed to celebrate happiness.

Valid observations. It was Mujib’s own cabinet members and partymen who formed the next government under veteran Awami League leader Khandakar Mushtaq Ahmed. At Mujib’s death, Abdul Malek Ukil, the Awami Speaker, heaved a sigh saying that the country was “relieved of a Zalem Firaun.” Humayun Rasheed Choudhury, another Awami Speaker, said when he was President Ershad’s Foreign Minister, that Mujib’s sins would not be cleansed even if he was hanged a hundred times (Ref: Weekly Suganda). Popular writer and filmmaker Humayun Ahmed described the post-August 15 scenario in his book Deyal: There were processions after processions in the streets. The truth was, they were the processions of happiness.

“His strolls around the corridor of power at times drew pity; he frowned at straight talk; he tried to destroy a dissident with his wrath. He loved the nation, yet he betrayed it. He had to pay with his life. August 15 was the accumulated wrath of the people,” wrote Enayetullha Khan (journalist-ambassador- minister) in the Weekly Bichitra.

After watching the movie, a school girl disgustingly commented, “He (Mujib) said, ‘my people cannot eat rice, so how can I eat?’, and then he went on smoking (his pipe).

Former Ambassador and Secretary to the Government Syed Muhammad Hussain wrote about Mujib, “The smoke from his most expensive brand Erin pipe tobacco created a veil across his eyes and his senses, and he could not see for himself, nor were his ‘honorable’ bandoleers honest enough to keep him informed about the people and about their ever-growing problems and the rising tide of disenchantment through deprivation, neglect and unkept promises.”

Bottomless Basket

True, Mujib’s time was termed as a Bottomless Basket due to heightened corruption. The poor had nothing to eat, not because there was no food but because of corruption in the ruling party and the administration. Mujib himself lamented that while others got “goldmines, I got a bunch of thieves.” Relief foodgrains from abroad were plenty but they did not reach the needy. They were dispensed on political considerations, or sold in black markets, while some finding way across the border to India. Men and animals fighting for a grub in the city garbage was a common sight. According to most estimates, 1.5 million people perished directly and indirectly in the “man-made famine” (per Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen) in 1974-75.

Street Scene in Mujib’s Bangladesh in 1974

Royal Wedding

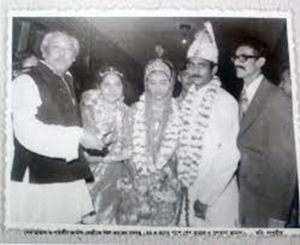

During the same period, Mujib’s two sons were married with lavish entertainment while people were dying of hunger just outside the Gonobhaban, the venue of the royal style wedding.

The contras: Royal-style Wedding of Mujib-sons in 1975

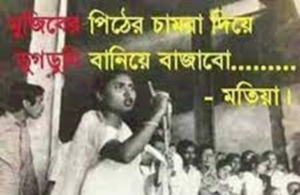

The Awami Students bestowed Mujib the title of Bangabandhu, the friend of Bengal. But Khuswant Singh, the well-known Indian journalist-writer-parliamentarian wrote in the Illustrated Weekly of India in 1975 that Mujib suffered from a folio de grandeur, and was unaware that people behind his back called him “Banga Satru,” enemy of Bengal. Motia Chowdhury, today’s top Awami leader, and Awami sycophant Shahriar Kabir called Mujib names (Bangasatru) on January 2, 1973 at a Paltan rally in Dhaka. (Ref: The Dainik Songbad January 3, 1973).

Why? Reasons are not far to seek. A few snapshots

Rakkhi Bahini: The Killer Machine

Mujib’s personal force of Rakkhi Bahini killed more than 30,000 political opponents, in other words, patriots. Mujib himself bragged on the parliament floor the killing of Siraj Sikdar, a top leftist leader.

Can one imagine how many additional lives would have been lost had there not been August 15?

Emergency

At the end of 1974, Emergency was clamped in the country. Fundamental Rights were suspended. Publication of all but four government-controlled newspapers was canceled. Political activities were banned. Anyone not toeing the official line was either in jail or not seen again. 62,000 dissidents landed in the already crowded jails.

Fourth Amendment

On January 25, 1975, Mujib orchestrated a constitutional coup in which he named himself the omni-powerful President, and declared himself the “Father of the Nation,” a nation that he never wanted. The New York Times of January 26, 1975 termed it a “death knell on the nascent democracy in Bangladesh.” Reportedly, there was a plan, through the Awami Chatra League route, to make Mujib a Lifelong President.

BAKSAL

The last nail on the dying nation was hammered in the form of Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), Mujib’s supposed Magnum Opus. BAKSAL was a socialist inspired one-party government. All other political parties were banned. The country was divided into 61 political districts, each to be administered jointly by a BAKSAL governor and a BAKSAL Secretary, chosen personally by the leader. The system was to take effect on September 1, 1975.

Noted historian and author K Ali wrote in the New Nation regarding Sheikh Mujib, “He was out and out a despotic ruler and snatched away fundamental rights of the people by introducing absolute dictatorship under a one-party system–there was hardly any doubt that the measure (one-party rule) was taken only to establish his permanent rule in the country without any opposition.”

Is it not, therefore, strange that Sheikh Mujib be called the Father and Architect of a Nation that he never wanted? More so, given the record of his 44-month autocratic and destructive rule?

————————————————————————————————

Chowdhury is a freedom fighter of Bangladesh in 1971, an accomplished author and a prolific writer.