Life in limbo

Life in limboThe half-million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh will not leave soon

In fact, more keep arriving

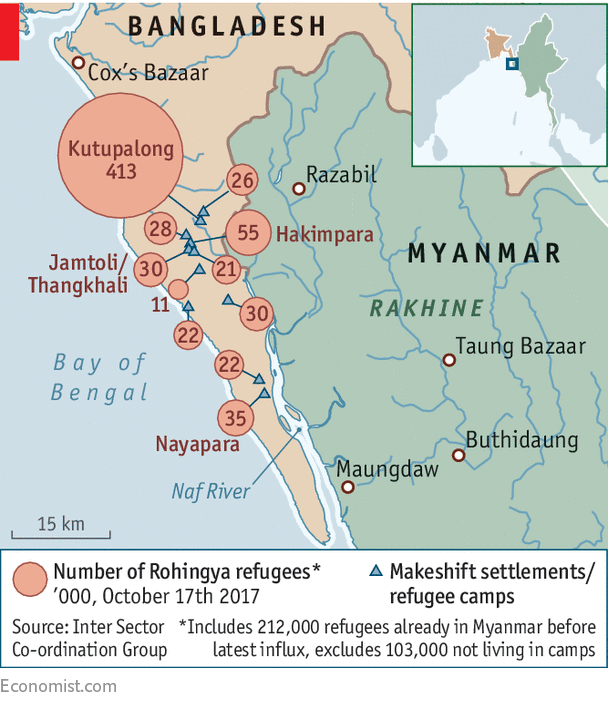

THE Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh does not seem temporary. It consists of thousands of tents made of plastic and bamboo spread across undulating terrain. Groups of male refugees carry long poles on their shoulders to erect even more. Fish, vegetables and fruit are for sale in a market. Half-naked children squat outside stalls selling sweets and biscuits; others splash in a muddy lake to escape the sweltering heat. Long wooden bridges connect parts of the camps divided by water; steps have been carefully carved into the hillsides to ease access to the shelters perched on them. In late August the camp housed around 100,000 Rohingyas, a Muslim minority group from Rakhine state in nearby Myanmar. Now four times as many live there.

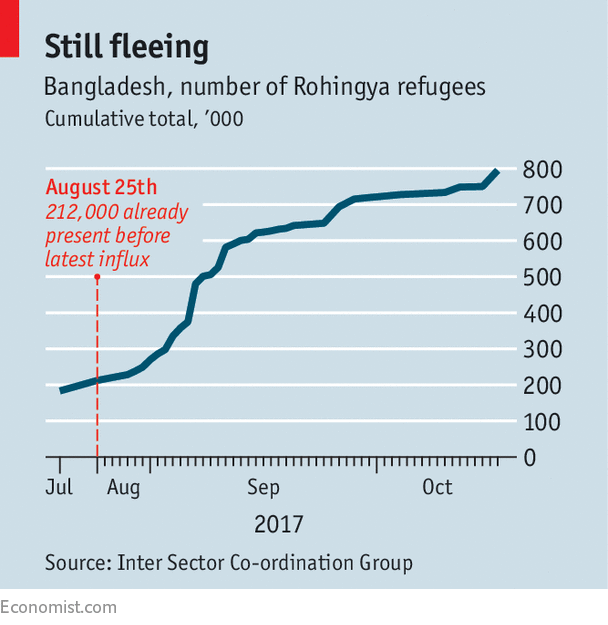

More than half a million Rohingyas have crossed the border to Bangladesh since August, joining hundreds of thousands who had already fled there from earlier pogroms (see chart). The exodus started after attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, a Rohingya extremist group, prompted the army to go on the rampage. The army’s violent campaign of retribution has been described by the UN’s top human-rights official as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

Those who have made it to Bangladesh are still in precarious circumstances. Ibrahim, a slight 10-year-old in the Nayapara camp, describes how his father was killed by the army; when he went to look for the body, he says, he saw Buddhist extremists decapitating corpses. Now he, his mother and his younger brother live in a camp where the walkways are lined with rubbish. They are hungry. “It would have been better if we had died there,” he says, with a blank expression on his face.

Existing camps, such as Nayapara and Kutupalong, the largest, have swelled to accommodate the new arrivals. Half a dozen new ones have also sprung up at the edges of paddy fields or on the outskirts of existing settlements (see map). They are often miserable places, with little access to clean water, health care or food. Refugees queue for hours to get rations. When it rains, the camps become mud-baths. Malnourished children stagger between tents; health workers talk of scabies and diarrhoea and warn of potential outbreaks of cholera. “Every third woman is pregnant,” says Harmeet Singh, a doctor with United Sikhs, an NGO.

Part of the problem is geography, explains Rob Onus, the head emergency coordinator for Médecins Sans Frontières, a medical charity which now has around 1,000 people working in southern Bangladesh. Unlike in Iraq or Syria, flat desert countries, it is hard to build a warehouse in southern Bangladesh: the best land has already been built on, and what little there is left is likely to be uneven, flood-prone or full of trees. Once a warehouse is built, medical supplies or food from it have somehow to be transported to the camps themselves, which are mostly inaccessible by car. Aid workers must navigate muddy paths, wooden bridges and steep slopes. The sheer size of the camps presents problems too. Refugees who live near the road may be able to get treatment; those farther in may not only not get it, but not even know that it is there.

Bangladeshi bureaucracy, which restricts what NGOs can and cannot do in the camps, does not help. Although it has been remarkably generous in allowing half a million people to cross its border, the government is sending “mixed signals” about how it intends to treat the refugees in the long run, says Chowdhury Abrar, a specialist in migration at Dhaka University. It appears committed to ensuring the Rohingyas go back to Myanmar. In early October the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar ostensibly agreed to draw up a plan for repatriation, although they are unlikely to agree on the terms of it any time soon. But it has also talked of creating a “mega camp” in Kutupalong, where aid workers fear that disease would spread even more readily, or of shipping the Rohingyas off to a flood-prone island.

Past precedent is worrying. Previous influxes of Rohingyas, in 1978 and then 1991, involved repatriation which some NGOs feared was forced rather than voluntary. Bangladesh abetted this by allowing conditions in the camps to deteriorate. According to a paper published in 1979 by Alan Lindquist, then head of the UN’s refugee arm in southern Bangladesh, “the objective of the Bangladesh Government from the beginning was that the refugees should go back to Burma [Myanmar] as quickly as possible, whatever they might feel about it.” In that instance, some 11,900 died in camps after the Rohingyas’ movement was restricted and food rations failed to arrive. Camps to house the internally displaced in Myanmar, which were meant to be temporary, have become permanent and squalid human sinkholes.

In Bangladesh, at least, things have improved. Refugees who have lived in the Nayapara camp since the 1990s say that in 2006, when the government allowed international NGOs to operate more freely, their lives improved dramatically. Many left the camps too: some to become Bangladeshi citizens or to travel to Saudi Arabia, Malaysia or Nepal with false documents. Some luckier ones were resettled as refugees in Britain, America and elsewhere.

As well as catching the attention of the international media, the current crisis has also become an issue of domestic Bangladesh politics. Posters along the roadsides proclaim Sheikh Hasina, the prime minister, to be the “mother of humanity”, while others declare her to be the “hope” of the Rohingyas. Yet despite this the government still refuses to use the term “refugees”, points out Mr Abrar, preferring to call them “forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals”. Rohingyas in the camps complain that they cannot take formal work or attend local schools and universities. One teacher in Nayapara complains that the certificate refugee children get is useless outside the camp. Local Bangladeshis, meanwhile, complain about rising food prices and the spread of methamphetamines manufactured in Myanmar.

Most Rohingyas want to go back to their homeland. They talk of the houses they lived in, the acres of land they owned, the shrimp farms they tended. Yet with that prospect seeming as elusive as ever, says Kim Jolliffe, a Myanmar-watcher in neighbouring Thailand, the parallel to their situation that most readily springs to mind is that of the Palestinians. That is not an encouraging analogy.