AS NEWS spread that security forces had killed Burhan Wani and two other guerrillas, admirers from across the Kashmir Valley headed to his village. Over 20,000 gathered for Mr Wani’s funeral on July 9th. The crowd was too dense to hold prayers; armed militants in its midst fired their guns in salute with no fear of arrest. Over the next days angry protests spread throughout the valley. At least 36 people were killed and 2,000 wounded, nearly all by police gunfire. At least 117 civilians, injured by blasts of buckshot, were likely to lose their eyesight, doctors said.

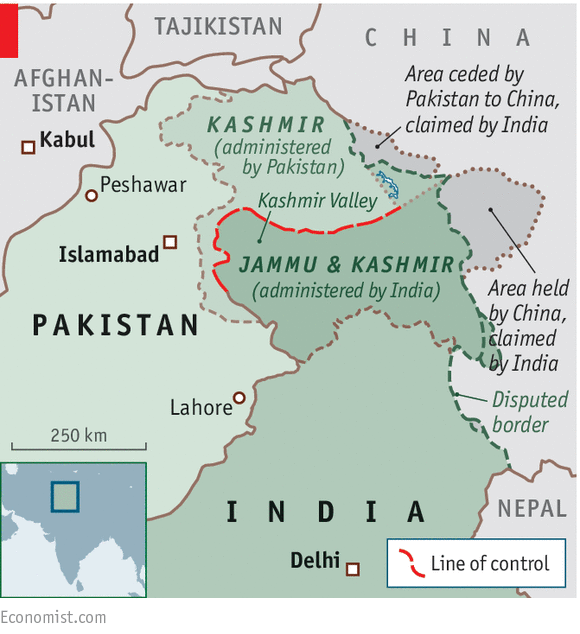

This was the worst outbreak of violence in Kashmir for six years, and yet it was dismally predictable. For months police, local leaders and residents had warned of imminent trouble in India’s northernmost state. True, the level of violence has dropped sharply from its peak in 2001 (see chart). The conflict has for decades squeezed the unhappy valley’s 7m inhabitants, nearly all Kashmiri-speaking Muslims, between the rival ambitions of India and Pakistan. Lately Pakistan has sharply curbed the export of guns and militants to a territory it long claimed as its rightful property, while India’s estimated 600,000 troops have underpinned a semblance of normality, allowing a return of tourism and the holding of regular elections.

The problem, say Kashmiri activists, is that relative calm has bred complacency in New Delhi, the Indian capital, while frustrations among Kashmiris, and especially young people, have grown. Some troubles, such as a lack of good jobs, are shared with other Indians. But in Kashmir these are compounded by a long, cyclical history of political manipulation and repression, where local politicians willing to “play India’s game” are discredited in Kashmiri eyes. Most of India’s mainstream press blithely disregards Kashmiri opinion, preferring to view the region simply as a playground for Pakistani-sponsored terrorism.

The current state government of Jammu & Kashmir, a polity that ties the Muslim-majority valley to adjacent regions of starkly different complexion, is an ungainly coalition between a traditional Kashmiri party and the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of the prime minister, Narendra Modi. The BJP has little understanding of and no patience for the Kashmiris’ disgruntlement. Its local partner, despite efforts to spread patronage and to exploit fears of Islamic radicalism, faces charges of acting as a stooge for New Delhi.

In recent years the number of armed militants has plummeted, while their romantic appeal has risen. Police reckon that fewer than 200 fighters now roam Kashmir’s mountains and forests. The difference is that many, perhaps most, of the renegades are no longer jihad-minded infiltrators from Pakistan, but local boys, often from the south of the valley far from the frontier. Worryingly, these militants now tend to be of higher social class, and adept at using social media.

Mr Wani exemplified this trend. Born in 1994 to a middle-class family, he went underground in 2010, during a previous round of violence, reportedly after his brother had been beaten and humiliated by policemen. Although local activists as well as at least one security official say there is little evidence that Mr Wani was directly involved in attacks on police, images of him in guerrilla clothes and armed with a rifle, against a backdrop of forests and mountains, spread via mobile-phone messages and Facebook. In a video posted in June he pledged that fighters would allow safe passage to Hindu pilgrims engaged in an annual trek to a mountain temple, and would accept the return of Hindu refugees from previous rounds of violence, but would resist attempts to establish colonies of Hindu returnees in Kashmir.

While Mr Wani’s example is not thought to have inspired more than a few dozen new recruits to armed insurgency, it held strong symbolic appeal. His death, in a safe-house besieged by an overpowering Indian force, followed a familiar pattern. Every few weeks guerrillas ambush Indian patrols, and every few weeks a suspected infiltrator or militant is killed in return. Since they are more often, now, local men, their funerals have swollen in size, and these in turn have fomented street clashes.

Many, even Mr Wani’s family, thought his death was inevitable, and would prove a catalyst for further violence. The surprise is that the anger seems to have caught out the Indian authorities. “The Indian government has got used to a firefighting approach,” says Basharat Peer, a Kashmiri writer who has chronicled repeated bouts of violence. “They don’t even see that by making no attempt at a political process to address Kashmiris’ real demands, they simply perpetuate the cycle.”

Source: The Economist