Kamal Ahmed | Sep 15,2022 New Age

FRUSTRATIONS over the role played by the media in Bangladesh can be felt profoundly in every corner of the country. Trust in media, to be more precise, so called mainstream media or traditional media is in free fall for quite some time. Many of us, people behind the media, journalists, editors and publishers often seek solace in blaming the emergence of new media phenomenon, internet and social media. No one can deny the fact that people have almost given up reading newspapers over morning tea, looking at flagship news programmes at their scheduled hours, may it be in the morning or in the evening. Instead, their eyes are on handheld devices, mostly smartphones for breaking news spread through Facebook status or Tweets. If anyone wants little more about any specific story, they will look for catch-up big stories or a video clip. But, what about our failures? What about our professional leaders, the editors? Haven’t they failed their audiences by not being able to keep engaged?

FRUSTRATIONS over the role played by the media in Bangladesh can be felt profoundly in every corner of the country. Trust in media, to be more precise, so called mainstream media or traditional media is in free fall for quite some time. Many of us, people behind the media, journalists, editors and publishers often seek solace in blaming the emergence of new media phenomenon, internet and social media. No one can deny the fact that people have almost given up reading newspapers over morning tea, looking at flagship news programmes at their scheduled hours, may it be in the morning or in the evening. Instead, their eyes are on handheld devices, mostly smartphones for breaking news spread through Facebook status or Tweets. If anyone wants little more about any specific story, they will look for catch-up big stories or a video clip. But, what about our failures? What about our professional leaders, the editors? Haven’t they failed their audiences by not being able to keep engaged?

Let’s examine two recent examples where our media failed to fulfil their duty and obligations. There were plenty of evidences including video footage aired by almost all TV channels in which foreign minister Abdul Momen was heard saying that he sought India’s assistance in keeping Awami League in power. There was no ambiguity, rather elaboration to explain why he thought India should be reminded of his government’s ability to best serve stability in the region. His party and some cabinet colleagues were more furious than others as his comment implied the party in power values India more than own people. Facing the fury, he issued a denial and blamed the media for misreporting, what he does frequently. There was no reason to carry his denial without pointing out the untruth. But, what we heard on our channels and read in the press was his untruth. No one flagged the denial as false. This kind of failure makes independent media a public relation (PR) platform of the government like Bangladesh Television and pushes away the audience who pay to learn facts, not propaganda.

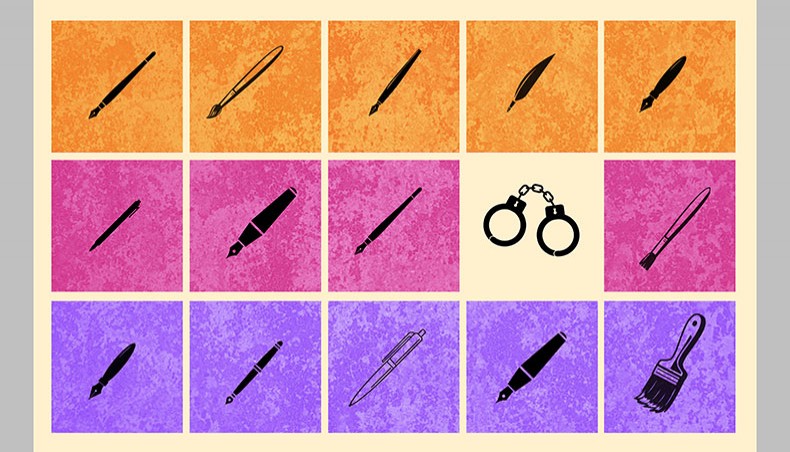

The mainstream media were unable to overcome the barrier of shadowy restraints including self-censorship, due to the intimidating environment created by arbitrary application of the Digital Security Act, random imprisonment, harassment and physical harm. The embarrassing silence on the issue in the mainstream media continued even after the opposition BNP and some other parties demanded an investigation into the alleged secret detention centre run by a state security agency. International rights organisations too made similar demands. Unless our editors find a way out of such conundrum where social media and foreign news organisations enjoy full freedom in exploring so called sensitive stories, but national media faces restrictive barriers, regaining lost trust would remain a distant dream. Besides the fear of annoying the government and its powerful supporters, a new trend of armchair journalism has emerged, which doesn’t require much legwork and field survey, essential elements of any investigative story. For television channels, studio-centric talk shows of selective and favoured experts have replaced expensive and painstakingly made documentaries.

It is true some of our editors have additional challenges, which often come from owners who either have their own business interests and are unwilling to annoy the government and some others either belong to the ruling party or have their own political ambitions. In the absence of any transparent policy for suitability of owning a public service media, be it a newspaper or a broadcasting outlet, the government’s discretionary power in granting licences has resulted in mushrooming of pop-up publications. Many of these publications are irregular, aimed at extracting non-media business favours or getting elevated in political parties and social organisations including trade bodies. Some of these media start their journey with fun-fare and extravagant investment, but without any long-term plan and necessary skilled journalists. As a result, these outlets become sick enterprises and increasingly inclined to government and corporate patronisation, sacrificing the core values of journalism and public interest. I know a few editors who have the credit of launching at least half-a-dozen newspapers, which ended up becoming sick or closed, but they are still luring journalists for another new venture.

Clearly, this unchecked discretionary power of the government in granting permissions for newspapers, magazines and TV channels has been used indiscriminately which has created an overcrowded and distorted media market. Even a business house owned by a fugitive has got so called declaration and since been publishing an English newspaper. A recent study on media ownership in Bangladesh by Professor Ali Riaz and Mohammad Sajjadur Rahman for the Centre of Governance Studies found three key overlapping features dominating the media ownership landscape of Bangladesh. First, many outlets are controlled by family members. Second, most owners of media outlets are directly or indirectly affiliated with political parties. And finally, almost all the media outlets are owned by big business groups with diverse financial interests. The study noted involvement and influence of party politics in the media’s ownership and noted that ‘four forms of association are conspicuous in this regard. First, whether a media outlet will get a licence largely depends on the government’s relationship with the entrepreneur. Second, politicians themselves become involved in media ownership. Third, influential ruling party politicians lobby for different business groups to help attain licences for media outlets. Fourth, ownership of the media changes hands to those who are connected to the incumbent political parties.’

Of course, the coming of moneyed people into the media landscape, as such, is not wrong. But, if one’s primary motive is to advance one’s own business interest, and not to serve the wider society, then such a publication should not be counted as a newspaper, but a corporate newsletter. Media outlets should be run professionally by professional editors with full independence and maintaining distance from the owner’s other interests. In many western democracies, owning a broadcast media requires a ‘proper and fit person’ test. And the objective of such a test is not to find allegiance to the ruling party or proving nationality, rather the person’s commitment to make the broadcast unit a public service entity. When a media owned by a real estate developer runs a story and commentary about Rajuk or Dhaka’s Detailed Area Plan, why shouldn’t it carry a disclaimer that it has some interest in it? Don’t the public have a legitimate expectation that the paper they are reading or the channel they are watching would be honest and truthful?

The complexities and conflicting interests in the present media landscape in Bangladesh have significantly increased job insecurity, reduced opportunity for professional training and skills development and journalistic freedom. Salary and other lawful entitlements have become so irregular in many media houses that a huge number of professional journalists have been enduring years of financial hardship and some of them have left the profession. Financial hardship and job insecurity, in the end, eroded journalistic integrity among many in the profession which led to formation of various interest groups and sub-groups. Both the government and non-government entities, particularly big businesses have been exerting undue influence on them through sponsorships and so called complimentary gifts. Reporters frequently accompany ministers and government delegations paid by the government, but editors overlook the potential conflict of interests. This trend is also emerging in corporate events abroad. We need to ask ourselves how long our audience will overlook such compromises with vested interests.

In the digital era, people seek more openness and transparency, so that any action can be accounted for. Disunity among journalists and editors, largely owed to the national political divide, has dealt a serious blow to the profession in Bangladesh, which is almost unheard of in any other country in our region and beyond. We are now at the crossroads where survival of the mainstream media will depend on the resurrection of journalism’s basics: telling the truth, holding power to account and empowering the powerless.

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist.