The pass-through of a sharp depreciation of the local currency accounted for half of the inflation surge seen in Bangladesh in the last financial year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The worsening current account and significant tightening of the global monetary conditions have put significant pressure on the taka. To stem foreign exchange reserves losses and help restore external balance, the central bank allowed the taka to weaken by close to 20 percent over 2022-23.

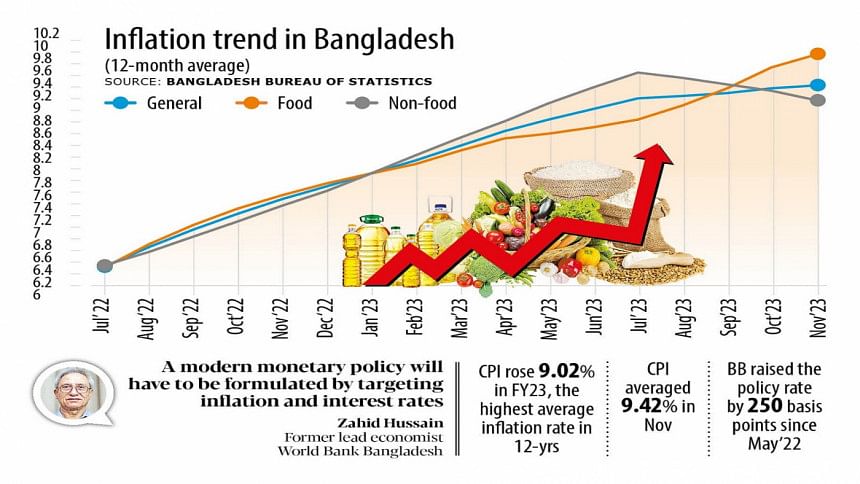

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 9.02 percent in FY23, the highest average inflation rate in 12 years. The price trend has continued in the current financial year of 2023-24, averaging 9.42 percent in November, figures from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics showed.

To estimate the pass-through of the exchange rate depreciation to inflation, an IMF paper uses the QPM (Quarterly Projection Model) model to decompose inflation into the contribution of individual shocks. The exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) is then estimated as a relative contribution of uncovered interest rate parity (UIP) premia shocks to overall inflation over the course of FY23.

The short-run ERPT ratio is estimated at 0.25, implying that the 20 percent taka depreciation in FY23 contributed to an increase in the overall price level by about 5 percent.

“In other words, of the total CPI increase of close to 10 percent in FY23, about half of it can be attributed (directly and indirectly) to exchange rate depreciation,” said the IMF in a report on inflation and the exchange rate policy.

Although initially triggered by temporary cost-push factors, higher inflation has over time gotten more entrenched as second-round effects emanating from multiple sources, including rising global commodity prices, bouts of the taka depreciation, and hikes in domestic fuel and energy prices took hold.

Responding preemptively to the adverse shocks, the Bangladesh Bank (BB) has been raising the interest rates since the middle of last year.

On October 4, the central bank raised the policy rate by 75 basis points, the highest one-time increase in a decade, marking a cumulative increase of 250 basis points since the start of the tightening cycle in May 2022.

However, the gradual pace of the monetary tightening appears to not be enough to stem the second-round inflationary pressures.

“A further tightening of the monetary policy stance is needed to bring inflation to the authorities’ target range over the medium term,” the IMF said.

Speaking to The Daily Star, Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka office, says there is no disagreement that depreciation has driven up inflation. However, other factors that were responsible for the elevated level of consumer prices were not cited by the IMF.

He said one of the factors was the higher credit growth, caused especially by the printing of new money to finance the budget deficit. Another factor is the US dollar shortage, which has forced the government to limit imports and caused a sharp depreciation.

Hussain said historically, the BB drew up monetary policies by targeting the broad money and the reserve money. “However, a modern monetary policy will have to be formulated by targeting inflation and interest rates.”

He said inflation had surged in many countries owing to global shocks brought on by the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war.

“Inflation has fallen in most countries. But Bangladesh has not been able to bring prices down as it did not act in the areas of domestic credit growth.”

In order to assess the extent of the required monetary tightening and evaluate the associated policy trade-offs, three QPM-based policy scenarios have been considered by the IMF.

The first scenario — the active policy — assumes that the BB actively determines its policy rate in every quarter of the forecast horizon to minimise expected inflation deviation from BB’s target over the monetary policy horizon up to two years, and keep the demand pressures checked, while ensuring that call money rate remains closely aligned with the policy rate.

The second scenario — the hawkish policy — assumes that the BB decides to bring inflation down to the target range by the end of FY24, before pursuing an active policy in adjusting the policy rate as in the first scenario.

The third scenario — the dovish policy — characterises BB’s current monetary policy stance, keeping the stance unchanged until the end of FY24, before pursuing an active policy in adjusting the policy rate as in the first scenario.

The simulation results suggest that inflation would remain elevated throughout FY24 under the “dovish” scenario and start decelerating gradually towards the target range only after monetary policy begins raising the rates.

The real output gains from this policy, compared to the “active policy” scenario, are short-lived and start dissipating quickly as the monetary policy tightens in FY25 and are largely undone by the end of the forecast horizon. The nominal exchange rate ends up about 3 percent weaker, compared to the “active policy” scenario.

On the contrary, the rapid disinflation under the “hawkish” scenario is costly, as the cumulative output loss reaches around 3 percent compared to the “active policy” scenario, but the exchange rate is stronger by about 1 percent, on the back of the tighter monetary policy.

“The optimal policy response is, therefore, believed to be between these two extremes—dovish versus hawkish, and would have to carefully weigh the benefits of disinflation against the associated output costs,” the IMF said.

“Given the lags in monetary transmission, the orderly disinflation process should take several quarters to two years to bring inflation to the target range, unless aided by favourable unexpected shocks.”

The IMF said a concerted but carefully calibrated monetary tightening will help restore price stability.

According to the paper, the more market participants believe that the central bank is determined to “do what it takes” to achieve price stability, the less it actually needs to “do it”. However, a central bank’s credibility is built over time through consistent policy actions and communication.

“Therefore, periods of economic challenges and uncertainty present opportune moment to build credibility for active and forward-looking monetary policy.”

Daily Star