Happiness and growth Economic growth does not guarantee rising happiness

An old paradox lives on

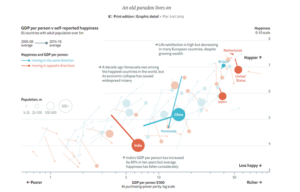

GDP per person v self-reported happiness

85 countries with adult population over 5m

average

average

Happiness and GDP per person:moving in the same direction moving in opposite directions

Philosophers from Aristotle to the Beatles have argued that money does not buy happiness. But it seems to help. Since 2005 Gallup, a pollster, has asked a representative sample of adults from countries across the world to rate their life satisfaction on a scale from zero to ten. The headline result is clear: the richer the country, on average, the higher the level of self-reported happiness. The simple correlation suggests that doubling GDP per person lifts life satisfaction by about 0.7 points.

Yet the prediction that as a country gets richer its mood will improve has a dubious record. In 1974 Richard Easterlin, an economist, discovered that average life satisfaction in America had stagnated between 1946 and 1970 even as GDP per person had grown by 65% over the same period. He went on to find a similar disconnect in other places, too. Although income is correlated with happiness when looking across countries—and although economic downturns are reliable sources of temporary misery—long-term GDP growth does not seem to be enough to turn the average frown upside-down.

The “Easterlin paradox” has been hotly disputed since, with some economists claiming to find a link between growth and rising happiness by using better quality data. On March 20th the latest Gallup data were presented in the World Happiness Report, an annual UN-backed study. The new data provide some ammunition for both sides of the debate but, on the whole, suggest that the paradox is alive and well.

There are important examples of national income and happiness rising and falling together. The most significant—in terms of population—is China, where GDP per person has doubled over a decade, while average happiness has risen by 0.43 points. Among rich countries Germany enjoys higher incomes and greater cheer than ten years ago. Venezuela, once the fifth-happiest country in the world, has become miserable as its economy has collapsed. Looking across countries, growth is correlated with rising happiness.

Yet that correlation is very weak. Of the 125 countries for which good data exist, 43 have seen GDP per person and happiness move in opposite directions. Like China, India is a populous developing economy that is growing quickly. But happiness is down by about 1.2 points in the past decade. America, the subject of Easterlin’s initial study, has again seen happiness fall as the economy has grown. In total the world’s population looks roughly equally divided between places where happiness and incomes have moved in the same direction over the past ten years, and places where they have diverged.

Sources: World Happiness Report, by John Helliwell, Richard Layard & Jeffrey Sachs (eds), UN, 2019; World Bank