In Britain, Bangladeshis have overtaken Pakistanis. Credit the poor job market when they arrived and the magical effect of London

MOST parts of Britain are doing better than Bradford, a smokestack town in West Yorkshire that has struggled since the collapse of the wool industry. But one comparison stings. Fatima Patel, the editor of Asian Sunday, a local newspaper, says Bradford’s leaders look ruefully at Tower Hamlets, a poor borough of London 200 miles to the south. And that comparison has an ethnic tinge, because Bradford is heavily Pakistani, whereas Tower Hamlets is the heart of Bangladeshi Britain (see maps).

In many people’s minds, and often in official statistics, the 447,201 people who called themselves Bangladeshi in the 2011 census and the 1,124,511 who identified themselves as Pakistani are lumped together. And the two groups have much in common. Mass immigration for both began in the 1950s. Both are largely working-class and Muslim. Both tend to vote Labour (see Bagehot). Both are concentrated in one business—restaurants in the case of Bangladeshis, taxi-driving among Pakistanis. But their fortunes are now diverging. And that says something about what it takes to succeed as an immigrant in Britain.

Even during the half-term holiday, the library in Morpeth School in Tower Hamlets is busy with mostly Bangladeshi children. Around three-quarters of the school’s pupils are so poor that they qualify for free school meals. A similar share do not speak English as their first language. And yet, last year, 70% got five good GCSEs, the exams taken at 16—much higher than the national average.

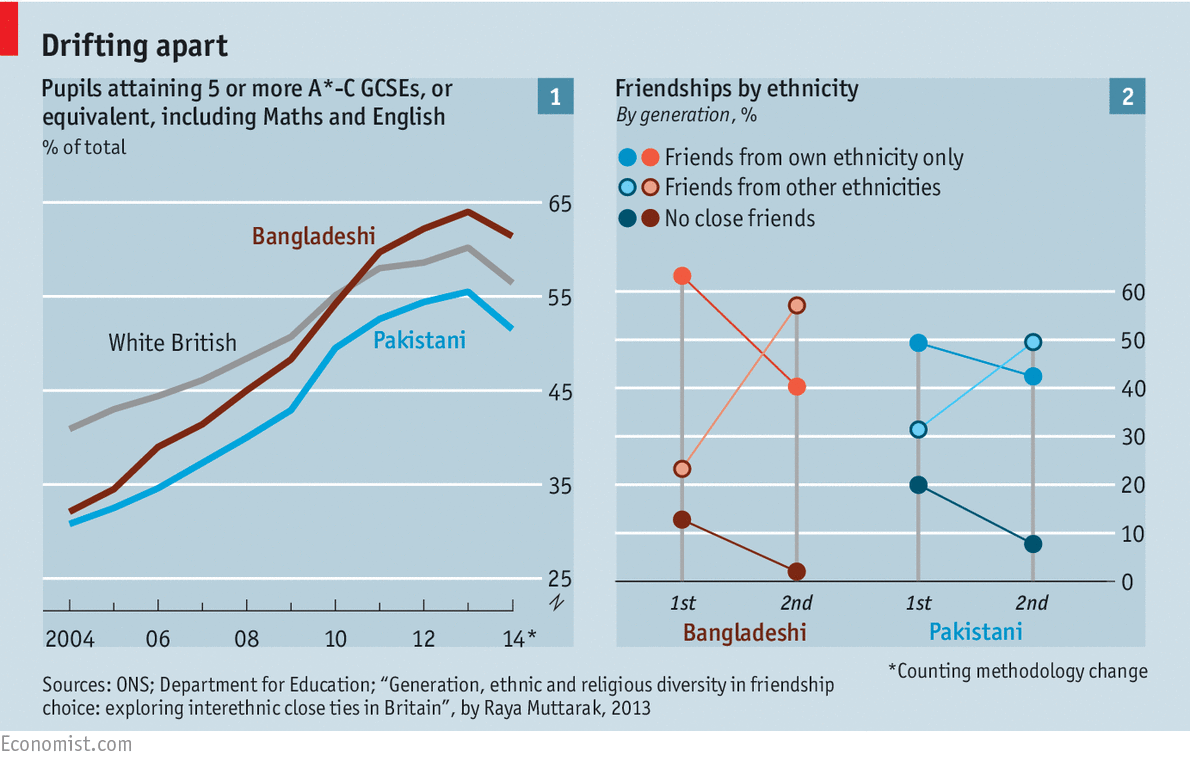

Pakistani pupils do not fare too badly in school either, considering how poorly educated and badly off their parents tend to be. But Bangladeshis overtook them more than a decade ago and have pulled farther ahead since then (see chart 1). Some 61% of Bangladeshis got five good GCSEs in 2014 compared with 51% of Pakistanis and 56% of British whites.

That will help their job prospects. Both Bangladeshis and Pakistanis have low employment rates because so many women do not work. But among the young, Bangladeshis are more likely to be studying or in work. And Yaojun Li, a sociologist at the University of Manchester, calculates that Bangladeshis’ average monthly household income, though still low, is now slightly higher than that of Pakistanis.

Bangladeshis born in Britain are also more likely than their Pakistani counterparts to socialise with people of a different ethnicity, according to another study (see chart 2). Both still overwhelmingly wed within their own ethnic group. But among young men, for whom marrying out is easier, 26% of Bangladeshis now do so compared with 17% of Pakistani youths.

The explanations lie partly in the past. Pakistanis—many of them from the rural Mirpur Valley in Kashmir—began to settle thickly in Britain in the 1960s. They often took jobs in the textile mills of the north and the foundries of the West Midlands.

Most Bangladeshis came later. Many men arrived in the 1970s as refugees, but the peak of migration was in the early 1980s, when the women and children turned up. They thus arrived when British industry was on the ropes—which was oddly lucky, suggests Shamit Saggar of Essex University. Though many were working in the rag trade, they had not committed themselves to one doomed industry. Pakistanis had: they suffered greatly from the collapse of British textile-making.

Those early jobs also drew the two groups to different bits of England. Today half of all Britain’s Bangladeshis live in London, compared to one-fifth of Pakistanis. Bangladeshis do not just tend to live in Britain’s most successful city, they also live in a particularly vibrant bit of it: Tower Hamlets surrounds the booming office district of Canary Wharf. Schools in London have improved much more than schools elsewhere, partly because they get more government money but also because the best teachers want to work there.

Pakistanis in London also benefit from the city’s improved schools; they do better there than in the rest of England. But research by Simon Burgess of the University of Bristol shows that geography does not explain the whole difference. Bangladeshis did better than Pakistanis both in London and outside the city in 2013.

East End advantage

The growing success of Bangladeshis appears odd because their living conditions are often so dismal. More than one-third live in social housing, compared with a national average of 18%. Near Morpeth School, a fence outside grotty flats is topped with upturned nails to deter intruders. Pakistanis are more likely to own houses. But, since those houses are often in the wrong place, that has not helped them much. Those living in decayed northern towns are tied to properties whose value is hardly rising, stopping them moving to more dynamic spots. “It is a stake that only allows you to move around the corner to equally bleak economies,” says Mr Saggar.

Cultural conservatism, which has deepened among many British Pakistanis, makes things worse. Cousin marriage is more common among Pakistanis than among Bangladeshis, as is the bringing over of partners from the subcontinent, argues Parveen Akhtar, a sociologist at the University of Bradford. Nuzhat Ali, a campaigner in the city, reckons such marriages are actually more common among recent Pakistani migrants than among their grandparents. The practice means that more Pakistanis in a city like Bradford are first-generation migrants than might be expected by now. It might also mean that young men are less driven to succeed—the desire to find a marriage partner being an unstated reason for going to university among people of all races.

The experience of Bangladeshis suggests that it is foolish to judge the success of immigrants after just a few years in Britain. It also bodes well for Somalis. Today they are among Britain’s most desperate migrants. But they, too, have the fortune to be concentrated in London. In parts of the city their school results are already improving sharply. They are struggling now—but their future could be much brighter. And their ambition is surging. Amina Ali, a Somali councillor from Tower Hamlets, is even hoping to be elected as a Labour Party MP in Bradford.

Source: The Economist