Criminalising dissent: What about muzzling opinions?

Holding or expressing opinions that do not go along the lines of the State is criminalised by law in many countries including ours. And the State often translates here as “people in power”. So, having differences of opinion with “people in power” can land anyone in serious trouble. Not surprisingly, this has been happening for years and under different governments in Bangladesh. Numerous dissenting voices had to pay—of course with the help of laws that have earned the labels “draconian” and “repressive” from rights activists.

When the State promotes suppression of dissenting voices in such a systematic way, what would be its implication in the greater society? Obviously, this sentiment trickles down to the public. People, especially those who feel connected with power circles, can take this as an opportunity to assert themselves and score some extra points for further political gain. This also serves the cause of the State to muzzle dissent. In this game of gains Abrar Fahad, a young Buet student, had to sacrifice his precious life on October 7. He had committed a “crime”, at least in the eyes of the killers, by posting his personal opinion on Facebook that was deemed not in line with the ruling party narrative. Certainly, Abrar is not the only one in the list of victims of this kind, but the latest and one of the most unfortunate.

In the aftermath of Abrar’s gruesome killing by members of the ruling party’s student wing, top government minister and Awami League general secretary Obaidul Quader said, “You can’t just beat someone to death for having a different opinion.” He did not say, “You can’t deem someone to be criminal for having a different opinion.” The minister’s statement was rightly and cautiously worded. The laws of the land do not permit anyone to “just beat someone to death for having a different opinion”. But it permits incriminating anyone “for having a different opinion”.

In 2018, Amnesty International made a statement regarding the Digital Security Act (DSA)—a draconian law massively criticised by international bodies—“The new Act is deeply problematic for three major reasons: ambiguous formulation of multiple sections that are vague that they may lead to criminalising of legitimate expression of opinions or thoughts; broad powers granted to authorities which are not clearly defined; and provisions which allow for removal or blocking of content and the seizure/ search of devices without sufficient safeguards.”

So, possible criminalising of legitimate expression of opinions or thoughts is at the core of a law and it wasn’t changed despite waves of criticism by rights activists and journalists in the country and abroad. Rather, DSA was used indiscriminately to stifle critical voices.

During last year’s road safety movement by the school students, Amnesty International observed about the draconian Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act, which has been replaced by DSA, “Section 57 has long been used as an instrument to criminalise people for freely expressing their views and opinions.”

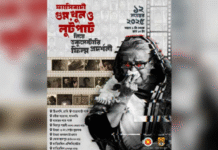

At that time prominent photographer Shahidul Alam also became a victim of this law. PEN International then wrote, “Shahidul was taken away because in a few posts on social media, he has been vocal and critical of the government’s human rights record. For exercising those legitimate rights, he is being punished.”

There were recurrent reports of arresting people for their Facebook posts. University teachers, government employees, among others, have been punished for expressing personal opinion on social media that hurt the feelings of ruling party men. In recent years, a number of cases were filed centring social media posts critical of the government. Mostly filed by government loyalists against dissenters, currently there are hundreds of cases to deal with in the Cyber Tribunal. After three persons getting arrested in such cases in May this year, Human Rights Watch said, “The Bangladesh government should stop locking up its critics and review the law to ensure it upholds international standards on the right to peaceful expression.”

Suing against dissenting voices, including journalists, has become a subject of competition among the government devotees; 84 cases were filed against the editor of the leading English daily of the country.

Another dimension has been added to stifling dissent in Bangladesh in the last few years as the country saw a wave of killing of bloggers for writings that were deemed inappropriate by the conservative section of the society. However, those incidents were claimed by religious extremists.

Taking all this into consideration along with the existing culture of impunity enjoyed by criminals connected to the ruling party, and the government’s hunting of dissenters, there may be a growing sense in pro-government party cadres that targeting people with opposing ideologies or opinions can be a good way for showing off loyalty. To them, being in the opposite side of a debate is a “crime”, writing one’s views on Facebook is an “offence”, and that’s why they called Abrar Fahad into the “torture cell” to interrogate him and find out who else shared his thoughts and opinions.

Most importantly, this was not an isolated incident in Buet; as media reports revealed the practice was going on for some time and the victims were not served justice after they reported these incidents to the university authorities. Why were they silent? Why were the university authorities afraid to act against Chhatra League’s activities that went on for years?

So, who is to blame for Abrar’s killing? Those who killed him? Or those who did not take any action to save him despite knowing what was going on? Or is it the state to blame that formulated laws criminalising dissent and encouraging the muzzling of critical voices?

Qadaruddin Shishir is a Dhaka based journalist and co-founder of BD FactCheck.