By MANU JOSEPHFEB. 18, 2015

NEW DELHI — Prime Minister Narendra Modi is an admirer of persistence, but perhaps not in India’s human rights activists. What many of them are persistent about is pursuing him.

On Tuesday, Mr. Modi gave a speech condemning religious violence of any kind. Yet many Indian activists and others see the prime minister, whose political origins are in nationalist Hindu organizations, as the archvillain in the 2002 rioting that claimed hundreds of lives, mostly Muslim, in the state of Gujarat, where Mr. Modi was the chief minister. In the years since, as Mr. Modi’s popularity has soared, two activists, Teesta Setalvad and her husband, Javed Anand, have been dogged in their efforts to bring him to trial, particularly in one case.

In any case, no substantial help arrived, and more than 60 people were slaughtered, including Mr. Jafri, who was hacked to pieces and burned. Mr Modi, who was within a few miles of Mr. Jafri’s house that day, said he did not learn of the incident until many hours later.

For years, Ms. Setalvad and Mr. Anand have been using the resolve of Mr. Jafri’s widow to pursue charges against Mr. Modi. They accuse him of facilitating violence against Muslims, a grave accusation that Indian courts have dismissed as unsupported by evidence.

Now it is not Mr. Modi but the activists themselves who face the possibility of prison. They could be arrested as soon as this week on charges of misappropriating money donated to help survivors of the Gujarat riots.

The authorities in Gujarat allege that of $1.5 million in donations received over the past 10 years by two trusts that Ms. Setalvad and Mr. Anand operate to provide relief and legal aid to riot survivors, about 15 percent was appropriated by them for “personal use” from 2009 to 2011.

Those transfers, the state has alleged, include reimbursements for credit card transactions. The state is specific about a few of their purchases: shoes for Ms. Setalvad, for instance, which the prosecutors describe as “branded” — an adjective apparently meant to suggest extravagance. She also purchased wine and “beauty products,” the state noted, as though bemused that an activist should consume alcohol or groom herself.

These are not the first charges that the authorities in Gujarat have brought against Ms. Setalvad. She was once accused of coercing a witness into giving false evidence about the riots, a charge of which she was absolved by India’s Supreme Court. The state also accused her of illegally exhuming the corpses of riot victims, an accusation the Supreme Court found “100 percent spurious.”

In a detailed response to the current accusations, the couple say they used their personal credit cards for both official and unofficial purposes, claiming reimbursements only for official expenses, a small fraction of the funds in dispute. The rest, they say, represents their own salaries, as well as expenses incurred in running the trusts and reimbursements to a company they own, which shares office space with the trusts and has paid for staff, utilities and other expenses. Ms. Setalvad told me that none of the trusts’ donors have raised concerns since the police began their investigation in March 2013.

In a hearing last week, Gujarat’s High Court cleared the way for the couple’s arrest. The Supreme Court delayed their arrest until at least Thursday.

This week, about 200 academics, writers and activists issued a statement in the couple’s defense that contained an implicit rebuke for Mr. Modi: “We see this as a clear case of the politics of vendetta launched with explicit intent to whitewash and efface from public memory the misdeeds of those who today wield political power in the state and center.”

Manu Joseph is author of the novel “The Illicit Happiness of Other People.”

Timeline of the Riots in Modi’s Gujarat

For more than a decade, Indians have asked whether Narendra Modi, India’s new prime minister, could have slowed or stopped the bloody 2002 riots in Gujarat. Muslims make up about 14 percent of the Hindu-majority nation founded on a secular constitution. Religion has been used by many parties for political gain. Following is a reconstruction of key developments before, during and after the riots.

Dec. 6, 1992

Hindus shouted and waved banners from the top of the Babri Masjid mosque in Ayodhya on Dec. 7, 1992.Douglas E. Curran/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Hindus Destroy Mosque in Religious Tinderbox

Tens of thousands of Hindus storm the Babri Masjid mosque in the northern city of Ayodhya, demolishing it with sledgehammers and their bare hands. They assert that the site was the birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram and was taken from Hindus in the 16th century by India’s first Mughal ruler, who built a mosque on the site.

Riots claim more than 1,000 lives, most of them Muslims, in the worst religious clashes since the nation’s bloody partition of British India in 1947.

Despite an order from India’s Supreme Court that the site remain intact, L.K. Advani, a prominent leader of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, or B.J.P., and the nationalist World Hindu Council, mobilizes the mob.

The incident shakes India’s secular identity, which is enshrined in its constitution. It is pivotal in the B.J.P.’s rise to power in 1998, after which it abandons its campaign pledge to build the Ram temple in order to win the backing of secular parties it needed to gain a parliamentary majority.

But the Ayodhya temple will remain a flashpoint, as later events in Gujarat reveal.

Feb. 27, 2002 at 7:43 a.m.

Coach S-6 carrying Hindu pilgrims is engulfed in flames at Godhra, a Muslim-dominated area in the western state of Gujarat.

Train Fire Kills Hindu Pilgrims

A train filled with Hindu pilgrims returning to Gujarat from Ayodhya stops in the town of Godhra, which is 40 percent Muslim and prone to religious violence. The Hindu activists had reportedly been chanting religious slogans. A scuffle begins with Muslim residents.

Within 15 minutes, Coach S-6 ignites, followed by cities, towns and villages across the western state of Gujarat.

The charred bodies of the 59 victims are displayed for the public in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city. Close aides of the state’s chief minister, Narendra Modi, who has only been in power a few months, endorse a widespread strike. These two decisions will be widely criticized as stoking anti-Muslim sentiment.

In 2005, an Indian government investigation finds that the fire was an accident and not caused by Muslims. The report is one of a number of politically competing inquiries.

Ninety-four people were put on trial ; 31 were convicted, 20 given life sentences, and 11 sentenced to death.

Feb. 28, 2002

A man walked past rubble in Ahmedabad a week into the worst episodes of Hindu-Muslim violence in India.Aman Sharma/Associated Press

Hindu Mobs Turn on Muslims For Weeks

Blaming Muslims for the deaths of the pilgrims, mobs of Hindus rampage, rape, loot and kill in a spasm of violence that rages for more than two months. Mothers are skewered, children set afire and fathers hacked to pieces.

About 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, are killed. Some 20,000 Muslim homes and businesses and 360 places of worship are destroyed, and roughly 150,000 people are displaced.

The two biggest massacres are in Naroda Patiya, where more than 90 people are killed, and at the Gulbarg Society, a Muslim housing complex where a rumor encouraged by a World Hindu Council leader incites a mob. Muslims take refuge in the home of Ehsan Jafri, a former member of Parliament from the Indian National Congress party. While the attacks continue for more than six hours, Mr. Jafri calls a number of influential people for help, but none arrive. Sixty-nine people are killed, including Mr. Jafri, who is hacked to pieces and burned.

There are widespread allegations that the B.J.P., which leads the state of Uttar Pradesh and the national governing party, and the World Hindu Council — both part of the same Hindu nationalist family — were complicit and in some cases instigated the mobs. The party and the council both deny the charges.

The day after the train attack, for example, police officers in Ahmedabad do not arrest a single person among the tens of thousands of angry Hindus.

A top state official tells one investigation panel that Mr. Modi ordered officials to take no action against rioters. That official was murdered. Thousands of cases against rioters are dismissed by the police for lack of evidence despite eyewitness accounts.

June 2002

Video: Mr. Modi walked out of a CNN-IBN program, “Devil’s Advocate” with Karan Thapar, in 2007 when questioned about the riots. Image: Shareefa Bibi with a portrait of her 18-year-old son who she said was killed by a mob. Kuni Takahashi for The New York Times

Modi Is Unapologetic

Mr. Modi is widely criticized for failing to console the state’s Muslims. In the last New York Times interview he gave, in 2002, Mr. Modi expresses satisfaction with his handling of the Gujarat riots and says his only regret is that he did not manage the news media better.

In 2012, he apologizes for any mistakes he may have made as the state’s chief. “There may have been a time when I hurt someone or when I made a mistake,” he says, adding, “I ask my 60 million Gujaratis to forgive me.”

His remarks to Reuters in 2013 spark controversy:

If “someone else is driving a car and we’re sitting behind, even then if a puppy comes under the wheel, will it be painful or not? Of course it is. If I’m a chief minister or not, I’m a human being. If something bad happens anywhere, it is natural to be sad.”

Mr. Modi tweeted his response and linked to the article saying, “In our culture every form of life is valued…People are best judge.”

Dec. 15, 2002

Video clip from the film “Final Solution” by the director Rakesh Sharma. J. Adam Huggins for The New York Times

Modi Is Re-elected

Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee of India chooses not to dismiss Mr. Modi for his handling of the riots. Instead, the B.J.P. calls for early elections. Mr. Modi begins a campaign based on Hindutva, or Hindu-ness, that aims to unite Hindus, and consolidate their votes, largely around a fear of Muslims. He frequently mentions the pilgrims who died in the train fire at Godhra, but never speaks of the Muslim victims of the subsequent riots.

Mr. Modi wins a landslide re-election victory in a referendum on his brand of politics and, some say, India’s character. By recasting his image as a business-friendly politician, Mr. Modi is now serving his fourth consecutive term as chief minister.

2004

A convicted man consoles his son before being taken to prison for his role in the 2002 riots. Associated Press

Supreme Court Intervenes

Investigations and prosecutions of those involved in the riots stall. In response, India’s Supreme Court reopens 2,000 cases, creates a special police team and transfers some trials out of Gujarat, resulting in hundreds of convictions.

Another crucial turning point comes when a top police official gives a lawyer representing the victims recordings of every cellphone call made during the worst of the rioting. The B.J.P. tries to suppress the investigation. The records are still being examined.

In late 2011, an Indian court finds 31 people guilty in the killing of 33 Muslims in Gujarat. They are sentenced to life in prison.

In 2012, a top lieutenant of Mr. Modi, Mayaben Kodnani, is given a 28-year prison term after being convicted of murder, arson and conspiracy. The judge says she is one of the key conspirators in the Naroda Patiya massacre.

2005

British High Commissioner James Bevan meeting Mr. Modi in 2012. Gujarat Information Bureau/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

U.S. Imposes Visa Ban on Modi

In an unusual step, the United States imposes a visa ban to rebuke Mr. Modi for his role in the Gujarat riots. Senior American officials will not reach out to him until February 2014, when he becomes a candidate for prime minister of India.

Britain ends a 10-year diplomatic boycott of Mr. Modi in October 2012.

October 2007

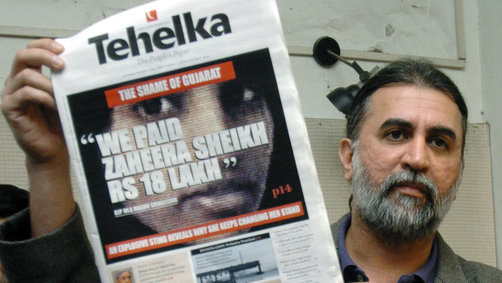

An NDTV news report on Tehelka’s investigation. Prakash Singh/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Leaders Are Taped Boasting About Roles in Violence

Tehelka, a weekly magazine, secretly videotapes senior police officers and politicians boasting about their roles in the 2002 killings — how they burned Muslim men, raped their wives and destroyed their homes.

The investigation renews focus on what role Mr. Modi might have played.

A B.J.P. politician says Mr. Modi had told him they had three days “to do whatever we could,” according to a transcript the magazine published the following month.

Mr. Modi dismisses the claims as politically motivated.

Sept. 30, 2010

Hindu devotees celebrating in Ayodhya after the decision was announced.

Kuni Takahashi for The New York Times

Site of Mosque Is Divided

An Indian court divides the disputed holy site in Ayodhya, concluding a case that has languished in the legal system since 1950 and that set off riots that killed a total of 2,000 people, most of them Muslims.

Nearly 200,000 officers are deployed across Uttar Pradesh as a precaution, but the public remains calm.

Dec. 26, 2013

Supporters of Mr. Modi after a court rejected a petition seeking his prosecution in December. Sanjeev Gupta/European Pressphoto Agency

Court Won’t Prosecute Modi

A court rejects a petition to prosecute Mr. Modi — filed by the widow of Mr. Jafri, who was killed during the 2002 rioting — saying there was insufficient evidence to prosecute him. This is the third time — in 2011, 2012 and 2013 — that Supreme Court panels have chosen not to prosecute Mr. Modi.

The manner in which the investigation was conducted has been contentious.

Mr. Modi welcomed the news on Twitter saying, “Truth alone triumphs.”

March 2014

Review Petition Filed Against Modi in Gujarat

Zakia Jafri, the widow of the former member of Parliament who was killed in a Gujarat massacre, filed a review petition in Gujarat High Court challenging last year’s judgment by the court in Ahmedabad. The next hearing in the case is on October 15.

Sept. 25, 2014

Lawyers of the American Justice Center, a nonprofit human rights organization acting on behalf of the two Indian plaintiffs, spoke at a press conference in New York on Friday. Jewel Samad/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

U.S. Court Issues Summons to Modi in Lawsuit Over 2002 Riots

A day before Mr. Modi is due to arrive for a much-touted five-day visit to the United States, a federal court in New York issues summons for Mr. Modi to respond to a lawsuit that over the 2002 riots. The summons are not likely to have any concrete effect on Mr. Modi’s visit because he enjoys immunity from lawsuits as a head of state. An attorney acting on behalf of him and the Indian government can seek to have the case dismissed, leaving a judge to decide the matter in several months. The complaint names two Indians as plaintiffs, one identified only as Asif and the other as Jane Doe, who, the complaint says, would not give her name out of “well-founded fear of retaliation from the state and nonstate actors.”

Human Rights Watch notes that regardless of whether Mr. Modi’s direct complicity can be established or not, he should be held accountable at the least for failing to stop or control the riots, according to John Sifton, the Asia advocacy director of the organization.