by Dave Jamieson

After American clothing brands scuttled a similar effort last year, Democrats and labor groups are trying to pressure the military into adopting more stringent labor standards for garments sourced overseas and sold in military base stores.

On Wednesday, the International Labor Rights Forum, a U.S.-based nonprofit watchdog, issued a scathing report that accused the military’s so-called exchange stores of “flying blind” in the sourcing of their private-label clothing, failing to “investigate or remedy safety hazards and illegal conditions” in the factories their clothes come from in countries such as Bangladesh.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) told HuffPost this week that he’s asked officials who run the exchange stores to develop a plan for tighter labor standards with regard to Bangladesh, where more than a thousand workers died last year in the Rana Plaza disaster. Under lobbying from U.S. retailers, a measure that would have forced the exchanges to do so was stripped out of this year’s military spending bill before it landed on President Obama’s desk in December.

“We’re reaching out directly to those that run the base exchanges and asking them to establish a standard for imports for Bangladesh,” Durbin said. “And I haven’t given up on the legislative approach.”

After the tragedies at Rana Plaza and Tazreen Fashions, where 112 died in a fire in 2012, U.S. lawmakers have called upon Western retailers and brands to make sure their clothes aren’t produced in sweatshops rife with labor and human rights violations. But as The New York Times reported in December, there’s a double standard at work here, as the U.S. government itself has been found to source clothes from dangerous facilities where workers’ rights are trampled.

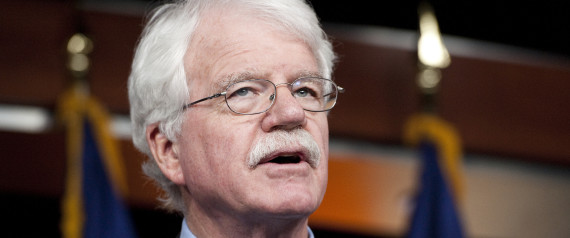

A handful of Democrats — Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.) in the Senate, and Reps. George Miller (D-Calif.) and Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) in the House — introduced an amendment to the military spending bill that would have required the exchanges to give preferential treatment to suppliers that sign the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a legally binding agreement hatched last year between clothing brands, labor groups and non-governmental organizations.

But major retailers who’d launched a separate, industry-led initiative, called the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, objected to the Democrats’ amendment, saying it would punish the alliance’s U.S. members who’d declined to join the accord. While the alliance has pledged more than $40 million in funding toward factory upgrades, its participants are not bound by the same legal commitments as those in the accord, and labor groups have criticized its lack of union involvement.

Although the Democrats’ measure died in the Senate, Durbin did manage to insert an amendment in the recently passed appropriations bill that requires the Defense Secretary to report to Congress whether the exchanges are sourcing clothes from factories that don’t comply with the accord. In a hearing this week, Durbin praised the Marine Corps for adopting a rule that manufacturers who produce clothing with Marine logos must abide by the accord’s rules. (Such clothes were found in the rubble of the Tazreen fire, prompting the new policy.) Durbin said he wants to see all government agencies adopt similar standards.

“It should be expanded across the board to all government agencies that we will continue to work with those companies that are providing a safe working environment for their workers, but we will not, with government funds, subsidize those that exploit workers,” he said.

In an interview with HuffPost, Miller was more forceful on the issue of clothing sold in the exchange stores. Miller said that although the stores provide an important service to military families, much of the clothing has “blood” on it and was produced through intimidation of the Bangladesh garment industry’s overwhelmingly female workforce.

The base stores, which are overseen by the Department of Defense, sell many of the same clothing brands found in typical U.S. department stores, as well as clothes made for their own labels. According to Miller, the government should hold itself to a higher standard on sourcing if it wants the retail industry to follow suit.

“If people would take the time to look at this, the purchase of these garments … they would see they’re purchasing garments that have blood all over their labels, and the abuse of women all over their labels,” Miller said. “This is not a new set of facts. It’s been the set of facts on the ground for many years. They [the exchanges] have been told about it in many audits that have been done. They’ve left that [responsibility] to the brands.”

Judd Anstey, a spokesman for the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, told HuffPost in an email that the service follows Department of Defense guidelines requiring that “military exchanges implement a program that ensures that private label merchandise is not produced by child or forced labor.” That includes complying with local safety and wage laws and allowing collective bargaining.

“Any violations of these standards by any manufacturer or subcontractor may be cause for immediate termination of any agreement,” Anstey wrote.

Spokespeople for the Navy Exchange Service did not immediately respond to requests for comment on Thursday.

In its report, the ILRF criticized the exchanges for relying on industry-led auditing for determining the safety of overseas factories. Labor groups are highly skeptical of such monitoring, since industry-sponsored audits have failed to prevent past disasters. According to the report, in some cases the exchanges have “no information” on the safety of the factories they source from, and at times rely merely on the “self-attestation” of the factories themselves.

“In other cases the military exchanges remain ignorant of flagrant violations in their supplier factories, because the industry audit reports failed to disclose them,” the report stated.

The ILRF recommended that the exchanges agree to abide by the accord’s principles, and that Congress hold the exchanges responsible for working conditions in their clothing supply chains.

“There needs to be much more rigorous oversight by the U.S. government — something that really creates a direct responsibility and ownership of the conditions,” Judy Gearhart, director of the ILRF, told HuffPost. “In our view, it’s not acceptable for U.S. government-owned companies to be not holding up the highest bar. It’s such a huge risk to the country’s reputation.”

Source: Huffingtonpost