Cheques and imbalancesThe government initiates a coup at Bangladesh’s biggest bank

Board members receive a visit from military intelligence

IT WAS an odd job for a spy agency. On the morning of January 5th military intelligence operatives phoned the chairman, a vice-chairman and the managing director of Islami Bank Bangladesh, picked them up from their homes and brought them to the agency’s headquarters, in Dhaka’s military cantonment. Polite officers presented the bankers with letters of resignation and asked them to sign. They did so. A few hours later the bank’s board, meeting under the noses of intelligence officers at a hotel owned by the army, selected their replacements.

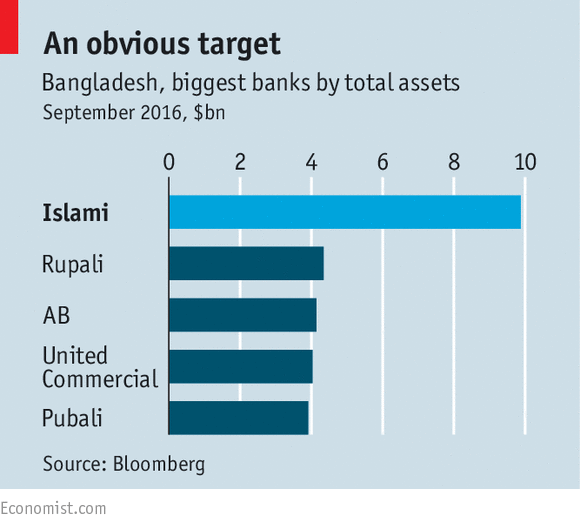

Islami Bank has been of interest to the government chiefly for its association with the Jamaat-e-Islami, Bangladesh’s biggest Islamist party. The bank is the country’s biggest (see chart), and operates in accordance with Islamic principles. Although the party only holds a minority stake in the bank, quiescent shareholders from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait had allowed it to appoint the top management.

The Jamaat advocates an austere, Arabian form of Islam, which has never had much of a following in relatively liberal Bangladesh. It has never won more than 12% in a national election. It does not help that the party opposed Bangladesh’s separation from Pakistan in 1971. Its student wing was the main source of recruits for a notorious pro-Pakistani paramilitary body. A special court set up by the ruling Awami League party in 2010 convicted most of the Jamaat’s senior leadership of war crimes. Those found guilty were jailed or hanged.

The trials destroyed the Jamaat as a political force, but its economic clout endured. Islami Bank accounts for a third of the assets of the Islamic banking industry. It has 12m depositors, 12,000 staff and a balance-sheet of $10bn. It handled more than a quarter of the $14bn Bangladeshi workers abroad sent home last year. Much lending in Bangladesh goes to those who know bankers or bribe them; Islami Bank appears to use more prudent criteria.

The Awami League seems to have worried that the resources of the bank might be used to help revive the Jamaat. A charity tied to the Jamaat, Ibn Sina Trust, which is also a shareholder in the bank, has a staff of 6,000. It runs 19 hospitals, and many schools and professional colleges. The bank also has a charitable arm of its own; its bosses were also replaced in January.

In recent months companies with ties to S Alam Group, a conglomerate based in Chittagong, Bangladesh’s second city, have built stakes in the bank, although the group denies any role in the shake-up. Senior staff from other banks in which the group holds stakes have been appointed to Islami Bank. The new chairman, Arastoo Khan, is seen as one of the country’s most effective bureaucrats, but has only recently turned his hand to banking. He declined to comment on the changes at the bank. But Ahsanul Alam, the new vice-chairman, says there is a risk that the management may open the “sluice gate” to political lending. Another board member says there have been changes in who is getting loans and how these loans are approved, with many of them going to borrowers from Chittagong. The central bank has chided the new management for violating proper procedures for loan disbursement.

The shareholders from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were kept in the dark about the boardroom coup, and complained bitterly about it. One of them, the Islamic Development Bank, based in Saudi Arabia, pointed out that it was only given three days’ notice of the board meeting in January, and therefore was not able to send anyone to attend it. It has questioned the rationale behind the changes, and pointed out that there was no proper recruitment process for the new managing director. It has also upbraided the government for suggesting that the foreign shareholders had endorsed the change of management, when in fact important decisions were being taken without their “knowledge or consent”. The government has assured foreign shareholders that it will not let politicians loot the bank.

The nominally secular Awami League has built a formidable one-party state since it came to power in 2009. Western diplomats are jittery after recent suicide attacks. They fear that the repression of competitive politics is undermining the country’s long history of secularism and tolerance. No one expects the government to permit a meaningful electoral contest in 2019. The sense in the capital is that Sheikh Hasina, the prime minister, will do whatever it takes to remain in office. Like the former bosses of Islami Bank, Bangladeshis are being presented with a fait accompli.