By AZIZ ANSARI

“DON’T go anywhere near a mosque,” I told my mother. “Do all your prayer at home. O.K.?”

“We’re not going,” she replied.

I am the son of Muslim immigrants. As I sent that text, in the aftermath of the horrible attack in Orlando, Fla., I realized how awful it was to tell an American citizen to be careful about how she worshiped.

Being Muslim American already carries a decent amount of baggage. In our culture, when people think “Muslim,” the picture in their heads is not usually of the Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar or the kid who left the boy band One Direction. It’s of a scary terrorist character from “Homeland” or some monster from the news.

Today, with the presidential candidate Donald J. Trump and others like him spewing hate speech, prejudice is reaching new levels. It’s visceral, and scary, and it affects how people live, work and pray. It makes me afraid for my family. It also makes no sense.

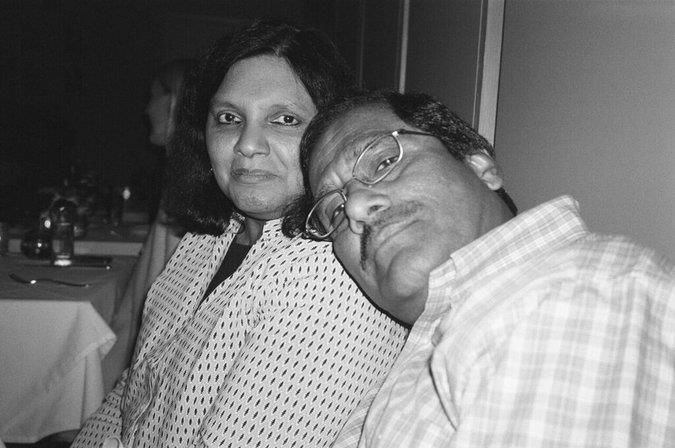

Aziz Ansari’s parents, Fatima and Shoukath Ansari Credit Photo courtesy Aziz Ansari

There are approximately 3.3 million Muslim Americans. After the attack in Orlando, The Times reported that the F.B.I. is investigating 1,000 potential “homegrown violent extremists,” a majority of whom are most likely connected in some way to the Islamic State. If everyone on that list is Muslim American, that is 0.03 percent of the Muslim American population. If you round that number, it is 0 percent. The overwhelming number of Muslim Americans have as much in common with that monster in Orlando as any white person has with any of the white terrorists who shoot up movie theaters or schools or abortion clinics.

I asked a young friend of mine, a woman in her 20s of Muslim heritage, how she had been feeling after the attack. “I just feel really bad, like people think I have more in common with that idiot psychopath than I do the innocent people being killed,” she said. “I’m really sick of having to explain that I’m not a terrorist every time the shooter is brown.”

I myself am not a religious person, but after these attacks, anyone that even looks like they might be Muslim understands the feelings my friend described. There is a strange feeling that you must almost prove yourself worthy of feeling sad and scared like everyone else.

I understand that as far as these problems go, I have it better than most because of my recognizability as an actor. When someone on the street gives me a strange look, it’s usually because they want to take a selfie with me, not that they think I’m a terrorist.

But I remember how those encounters can feel. A few months after the attacks of Sept. 11, I remember walking home from class near N.Y.U., where I was a student. I was crossing the street and a man swore at me from his car window and yelled: “Terrorist!” To be fair, I may have been too quick to cross the street as the light changed, but I’m not sure that warranted being compared to the perpetrators of one of the most awful incidents in human history.

The vitriolic and hate-filled rhetoric coming from Mr. Trump isn’t so far off from cursing at strangers from a car window. He has said that people in the American Muslim community “know who the bad ones are,” implying that millions of innocent people are somehow complicit in awful attacks. Not only is this wrongheaded; but it also does nothing to address the real problems posed by terrorist attacks. By Mr. Trump’s logic, after the huge financial crisis of 2007-08, the best way to protect the American economy would have been to ban white males.

According to reporting by Mother Jones, since 9/11, there have been 49 mass shootings in this country, and more than half of those were perpetrated by white males. I doubt we’ll hear Mr. Trump make a speech asking his fellow white males to tell authorities “who the bad ones are,” or call for restricting white males’ freedoms.

One way to decrease the risk of terrorism is clear: Keep military-grade weaponry out of the hands of mentally unstable people, those with a history of violence, and those on F.B.I. watch lists. But, despite sit-ins and filibusters, our lawmakers are failing us on this front and choose instead to side with the National Rifle Association. Suspected terrorists can buy assault rifles, but we’re still carrying tiny bottles of shampoo to the airport. If we’re going to use the “they’ll just find another way” argument, let’s use that to let us keep our shoes on.

Sign Up for the Opinion Today Newsletter

Every weekday, get thought-provoking commentary from Op-Ed columnists, The Times editorial board and contributing writers from around the world.

Xenophobic rhetoric was central to Mr. Trump’s campaign long before the attack in Orlando. This is a guy who kicked off his presidential run by calling Mexicans “rapists” who were “bringing drugs” to this country. Numerous times, he has said that Muslims in New Jersey were cheering in the streets on Sept. 11, 2001. This has been continually disproved, but he stands by it. I don’t know what every Muslim American was doing that day, but I can tell you what my family was doing. I was studying at N.Y.U., and I lived near the World Trade Center. When the second plane hit, I was on the phone with my mother, who called to tell me to leave my dorm building.

The haunting sound of the second plane hitting the towers is forever ingrained in my head. My building was close enough that it shook upon impact. I was scared for my life as my fellow students and I trekked the panicked streets of Manhattan. My family, unable to reach me on my cellphone, was terrified about my safety as they watched the towers collapse. There was absolutely no cheering. Only sadness, horror and fear.

Mr. Trump, in response to the attack in Orlando, began a tweet with these words: “Appreciate the congrats.” It appears that day he was the one who was celebrating after an attack.

Aziz Ansari, an actor, writer and director, is a creator of the Netflix series “Master of None.”

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTOpinion), and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter.