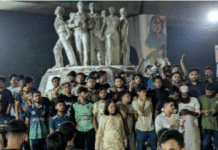

Students’ protests against discrimination, law enforcers on university campuses, brutal crackdown by law enforcement personnel, shocking violence and rage against the citizens, complete internet blackout, and finally a nationwide curfew—this series of events have been overwhelming, to say the least, for the whole nation. The young generation of today is fighting and struggling, in countless ways and forms, in a free country. So, as we stand in 2024, after 53 years of independence, tagging those who hold a different opinion as “anti-state” and “anti-independence” has become an outdated and overused tactic. This tagging has caused widespread violence against students, leading to deaths and injuries.

Over the last decade, we have seen several student uprisings demanding some of the basic rights. Each time, a similar formula has been applied, starting with alleging their affiliation with other political entities and ending with a combined Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL) and police brutality. However, the senseless brutality, mass arrests of students and social media blackouts that the nation has witnessed this time is unprecedented. This time, it is creating a prolonged state of fear. Law enforcement personnel are still roaming the streets. One of the most powerful slogans heard during the protests was “proshason jobab chai,” which is basically asking to hold the authorities accountable for their inaction and hoping for proactive steps. But the very authorities that are accountable for protecting us have failed to do so—be it the university authorities, the police, or the government itself.

This brings forth a series of questions. Who is fighting against whom? Why did the vice-chancellors of most of the public universities essentially disown their students? Why did law enforcement personnel open fire against unarmed students? Why did the authorities use such force against the students who want but the bare minimum of equity?

The answers to all these questions go beyond the current movement. The students know the system is becoming increasingly rotten. Still, they want reforms to ensure a just system, even after knowing that it may not make much difference because many a job is now for sale. As the movement got momentum and the students felt they were being insulted, they understood it was time to continue fighting, not only for the reformation of the system but also to find their voices because, apparently, no one else has the courage to do so.

Bangladesh has a long history of student movements. The public universities, especially Dhaka University, have their pride in leading the successful and justified movements that have always shifted the course of history. So, why did a student movement that started with a demand to reform a discriminatory and unconstitutional system get so violent?

Many are now attempting to satisfy their own agendas. But in this age of technology, countless video footage showed BCL and law enforcement agencies’ brutality against the protesters clearly. It should not be difficult for them to find out the people who killed so many people and were involved in the looting and destruction of public properties.

This leads to another question: can the students and the nation expect transparency and justice from these very agencies responsible for this violent crackdown?

Even before the nationwide complete shutdown on July 18, the whole country was shocked to see the degree of police brutality when Abu Sayed, a fourth-year university student in Rangpur, was shot dead. Some ministers’ comments during this crisis were neither responsible nor sensitive; rather they were provocative against students who were practising their democratic rights. During a crisis, the true face of both the people and the system comes out. This nationwide movement is not an exception, of course; it is rather doing an excellent job of revealing the failure of our institutions. The damage is bigger than it appears on the surface. Will the students who saw the police beat up their friends, or who got stuck in a place and saw armed people, along with law enforcement members, waiting to attack them, or simply witnessed their friends getting shot and die, get over this trauma that their very own government agencies brought upon them? The mistrust created among general students and mass people will have a long-term implication.

Now, the final question: was the situation unavoidable? The authorities eventually admitted that the students’ demands were logical, and reformed the quota system. But why did logic require these deaths to be considered and applied? The cruelty that some agencies showed against the country’s future generation is upsetting and terrifying. Will they ever be able to recover from that? More importantly, do they want to at all?

Daily Star