Last update on: Sat Jun 14, 2025 02:46 PM

Almost a year on from the Monsoon Revolution, the euphoria of victory against the monstrous Hasina regime has faded, and the prospects for a peaceful democratic transition hang in the balance. The interim government has found itself getting entangled in various policy controversies. The National Citizen Party, formed by the youth leaders who spearheaded the uprising last July, is finding it difficult to gain political traction. Radicals within and outside the government try to seize every opportunity to push their anarchic agenda. Meanwhile, the largest democratic party, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, appears unsure of its own reform agenda and vision.

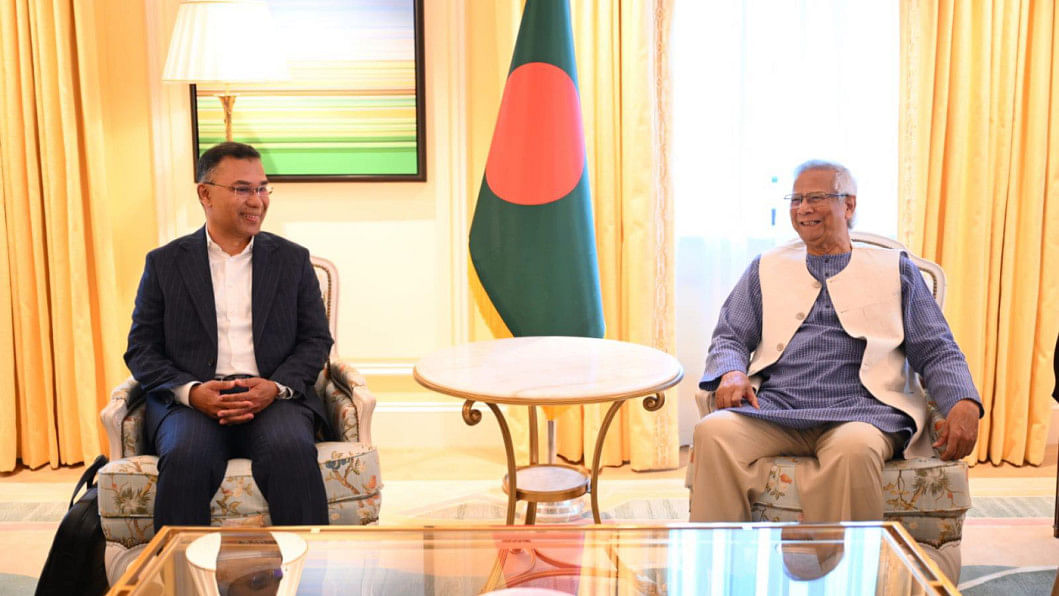

It is against this backdrop that the Chief Adviser of the Interim Government Prof Muhammad Yunus and the BNP’s Acting Chairperson Tarique Rahman met in London on June 13. The nation waited with bated breath for the outcome of the meeting. Our history is full of such meetings where the principals fail to find common ground. The early signs are that this time might be an exception. It seems that the two leaders have agreed to work towards a smooth democratic transition, with agreements on reforms paving the way towards a pre-Ramadan election. The Nagorik Coalition—a civil society platform advocating reforms related to citizen’s rights and building democratic institutions—has proposed a clear, feasible pathway that can lead to a peaceful, durable democratic transition by next Ramadan.

A durable democratic transition requires two things: a high-turnout election and consensus on some critical reforms. Let us take these elements in turn.

Election timing is not just a matter of polling day. A set of activities required for the election must begin immediately. An ordinance needs to be issued by the end of July allowing those who have turned 18 in 2025 to be enrolled in the voter roll. The voter list could be finalised by the end of October. This could pave the way for the announcement of the election schedule in late November, with the election taking place before Ramadan.

And it is critical for a democratic transition that the election takes place before Ramadan, not afterwards. Bangladesh has not had a large-scale national election since 2008. It is well understood that the functioning of government machinery, and indeed of society as a whole, changes during the month of fasting. Eid is arguably the biggest celebration for most Bangladeshi families. Furthermore, April is the exam season, and educational institutions play a vital logistical role in the conduct of elections.

That the chief adviser even floated a post-Ramadan April election, defying these basic social realities, is difficult to fathom. Back in August, he had said the timing of elections would be determined by politicians. Well, most politicians who would actually campaign for election on the ground—as opposed to shouting on social media—would welcome a pre-Ramadan election.

It is therefore welcome news that the chief adviser has indicated that, if sufficient progress is made on the reform front, a pre-Ramadan election is very much possible.

The democratic political parties are not as far apart on critical reforms as one might believe from the daily din of disinformation on social media. For example, there is general agreement on a hundred-member upper house, one hundred female MPs, an election-time non-partisan government, and the strengthening of parliamentary committees and institutions such as the Election Commission. The disagreement is about the mechanisms.

An upper house of parliament with members chosen in proportion to the votes won by the parties in the general election could, in fact, go a long way towards avoiding the difficulties we have had in the past with caretaker governments or weakening institutions. On the other hand, if the upper house simply reflects the seats won in the lower house—as preferred by the BNP—then the risk is that, over time, its members will resemble the party hacks that made up Hasina’s parliament.

Tarique Rahman was the first major politician to propose the upper house. Surely, he would want to see an upper house that actually works, and not the kind of circus one associates with Hasina’s parliaments.

A similar point can be made about the one hundred female MPs.

Politically, there is nothing for the BNP to lose from agreeing to a proportionally represented upper house with a role to play in the formation of the election-time non-partisan government, and in ensuring better parliamentary oversight and the strengthening of institutions. Indeed, as the largest democratic party, the BNP is likely to maintain the largest number of upper house members in the foreseeable future under proportional representation. And as a party that is expected to govern, it has everything to gain from better institutions. Similarly, the party stands to benefit most from directly elected female MPs, simply because it is the largest democratic party with a nationwide presence.

That is, there is both national interest and narrower partisan logic for the BNP acting chairperson to agree in principle to these key reform ideas.

The chief adviser had expressed his desire to see the Rohingyas celebrate Eid-ul-Fitr 2026 in their homeland. There is little chance that he would see that wish fulfilled. Perhaps he would be better off spending the next few months solely focusing on whatever needs to be done to give the nation a democratically elected government by Ramadan 2026.

Fahim Mashroor and Jyoti Rahman are members of Nagorik Coalition.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.