Last update on: Wed Sep 24, 2025 08:05 AM

For years, Bangladesh’s economic narrative has been one of remarkable ascent, a story punctuated by the steady hum of sewing machines and the quiet revolution of women entering the workforce in unprecedented numbers. The nation’s climb up the economic ladder was, in many ways, built on the shoulders of its women, particularly in the garment industry that became the engine of its growth. Which is why the latest figures from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) feel so disquieting, like a sudden, unexpected silence in a once-booming factory. In just one year, the country’s labour force shrank by 17 lakh people, and the overwhelming majority of those who left were women. This isn’t just a statistical blip; it’s the first contraction since 2010, and it signals a potential unravelling of hard-won social and economic gains.

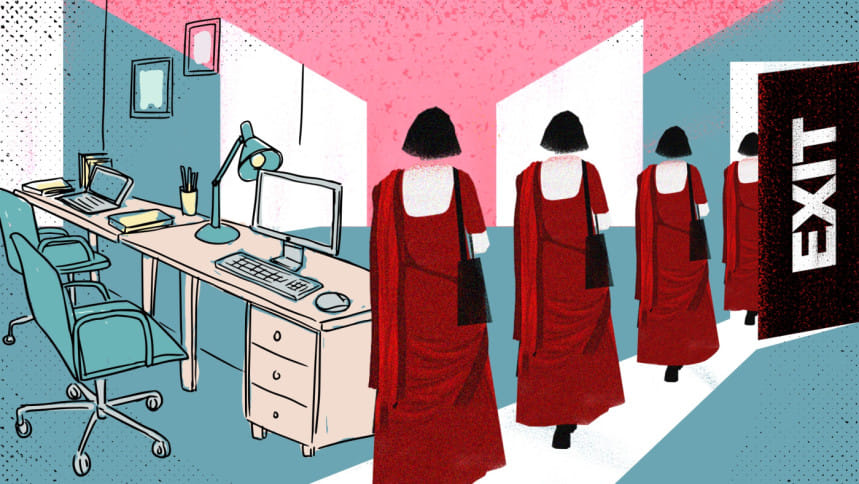

To understand what’s happening, we have to look beyond the single, stark number. The data reveals a tale of two realities. Male participation in the labour force held essentially steady, while female participation plummeted from 2.53 crore to 2.37 crore. This means that nearly all the losses are concentrated among women, effectively erasing a significant portion of the gains made over the last decade and a half. From this perspective, the decline feels less like an economic adjustment and more like a quiet exodus. The question, of course, is why. Why are women, who have been so integral to the nation’s progress, now stepping back?

The answers are complex, woven from global economic shifts and our own entrenched local realities, but they are made more urgent by a particularly troubling detail: this decline is happening prematurely. Bangladesh is experiencing this dip in female labour force participation at a relatively low level of per capita income, a deviation from the typical development pathway that is concerning. There’s a known, almost paradoxical, economic phenomenon at play here. As a country develops, women’s participation in the labour force often follows a U-shaped curve. It is high in a poor, agrarian economy, dips in the middle stages of development as education enrolments rise, and then climbs again once the economy matures and creates the right kind of jobs. In other words, we may be hitting that difficult middle curve, but we are hitting it too early and from a position of greater economic fragility. Put simply, more of our daughters are in school and university—a tremendous success—but our economy isn’t yet creating the types of jobs they expect and deserve once they graduate, leaving a generation of educated women in a precarious limbo between aspiration and reality.

This gap between aspiration and opportunity is critical. For women with little formal education, the traditional gateway into the formal economy—the garment sector—is itself transforming. Automation and advanced technology are reducing the reliance on vast numbers of low-skilled workers. The share of women in this industry has fallen significantly, meaning the very door that powered their entry is now narrowing. These women now require more skills to remain competitive, and without large-scale, targeted training programmes, many are being left behind.

For the growing number of educated women, the barriers are different but equally formidable. What this implies is a landscape of frustration. The modern service sector jobs in education, healthcare, finance, or hospitality that should naturally absorb them are not being created fast enough. Even when such jobs exist, the absence of supportive infrastructure—reliable public transport, safe workplaces, and most crucially, affordable childcare—pushes them out. The burden of unpaid care work at home remains overwhelmingly on their shoulders, a social factor that no economic policy can afford to ignore. So, a young woman might graduate with a degree but find no job that matches her qualifications, or she might find one but be forced to choose between her career and her family because the support system simply isn’t there.

Furthermore, we must be careful not to romanticise the previous growth in numbers, as a significant portion of that reported participation was based in rural areas and often consisted of unstable, unpaid, or low-quality work. Much of this labour is temporary; for example, when a male family member migrates to the city or abroad for work, a woman may take on his agricultural duties. However, land ownership and earnings typically remain under the control of male relatives, meaning women often work without formal payment or financial autonomy. This kind of precarious, invisible labour does not equate to genuine economic empowerment. The real concern, therefore, is not just the recent decline, but the persistent failure to create high-quality, stable, and formal jobs for women, particularly in urban areas and modern sectors. Ultimately, the pattern of structural transformation in Bangladesh has failed to ensure that women are successfully integrated into the new economic landscape.

The consequences of this reversal are profound and far-reaching. On a macroeconomic level, it represents a massive waste of talent and potential, a drag on national productivity and GDP growth that the country can ill afford as it aims for higher development goals. But the true cost is human. Declining female labour force participation threatens to reverse decades of social progress. Economic independence is a key driver of better health outcomes, educational attainment for children, and greater autonomy for women within their households and communities. When that independence is curtailed, all these other gains become vulnerable.

Addressing this challenge requires a move beyond simplistic solutions. It demands a multipronged strategy that acknowledges the different needs of different women. For the urban educated, it means aggressively creating opportunities in the service sector and building the infrastructure—childcare centres, flexible work arrangements, and safe transport—that allows them to thrive. For those displaced by automation in manufacturing, it means investing in large-scale, targeted skills development and reskilling programmes. And for rural women, it means breaking down the barriers to entrepreneurship—access to capital, markets, and information—so they can build sustainable businesses in the non-farm sector.

The declining curve on the chart is more than a data point—it is a warning. It tells us that the path of progress is not linear or guaranteed. The momentum that lifted so many women into the economy is faltering, and without deliberate, thoughtful intervention, we risk not just stalling but sliding backwards. The strength of Bangladesh’s economy has always been its people. To continue rising, it cannot afford to leave half of them behind.

Dr Selim Raihan is professor in the Department of Economics at Dhaka University, and executive director at the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM). He can be reached at selim.raihan@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Source: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/views/news/why-women-bangladesh-are-leaving-the-workforce-3992736