The United States has a reputation for driving the course of world affairs — but it doesn’t necessarily deserve it.

By

Does U.S. foreign policy matter? Of course it does, but how much?

These days, both proponents and critics of America’s omnipresent role in the world tend to portray U.S. foreign policy as the single most important factor driving world affairs. For defenders of global activism, active U.S. engagement (including a willingness to use military force in a wide variety of situations) is the source of most of the positive developments that have occurred over the past 50 years and remains critical to preserving a “liberal” world order. By contrast, critics of U.S. foreign policy both at home and abroad tend to blame “U.S. imperialism,” the “Great Satan,” or mendacious Beltway bungling for a host of evil actions or adverse global trends and believe the world will continue to deteriorate unless the United States mends its evil ways.

Both sides of this debate are wrong. To be sure, the United States is still the single most influential actor on the world stage. Although its population is only about 5 percent of humankind, the United States produces roughly 20 to 25 percent of gross world product and remains the only country with global military capabilities. It has security partnerships all over the world, considerable influence in many international organizations, and it casts a large cultural shadow.

![]()

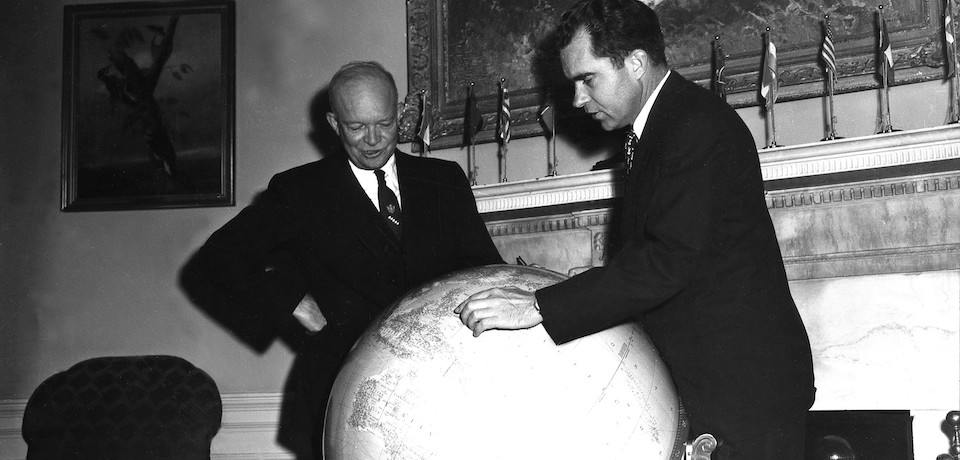

The United States, in short, is hardly the “pitiful, helpless giant” that Richard Nixon once feared it would become. At the same time, it deserves neither all of the credit nor all of the blame for the current state of world politics. Let’s unpack these competing claims and see where each one goes astray.

For defenders of the U.S.-led “liberal world order,” America’s global role is the source of (almost) All Good Things. As Samuel P. Huntington put it more than 20 years ago, U.S. primacy is “central to the future of freedom, democracy, open economies, and international order in the world.” Or as Politico’s Michael Hirsh once wrote (possibly after one too many espressos), “the role played by the United States is the greatest gift the world has received in many, many centuries, possibly all of recorded history.”

Hyperbole aside, that self-congratulatory worldview is almost a truism within the U.S. foreign-policy establishment. In this version of recent world events, America’s “Greatest Generation” defeated fascism in World War II and then went on to found the United Nations, lead the global campaign for human rights, spread democracy far and wide, and create and guide the key economic institutions (World Bank, IMF, WTO, etc.) that have produced six decades of (mostly) steady economic growth. By leading alliances in Europe and Asia and deploying its military force far and wide, the United States has also ensured six decades of great power peace. Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright captured this narrative perfectly when she famously said the United States was the “indispensable nation” that sees further than others do, and all three post-Cold War presidents embraced and endorsed that view as well.

There’s more than a grain of truth in some of these claims, but defenders of American “leadership” badly overstate their case. Yes, we’ve seen 60-plus years without a direct clash between major powers, but the nuclear revolution probably has as much to do with the reluctance of great powers to fight each other as with the global military presence of the United States. Moreover, as John Mueller has argued, the past few decades of peace may also be due to cultural and attitudinal changes occasioned by the destruction and brutality of the two world wars. Nor should we forget Europe’s own efforts to build a supranational organization — beginning with the original European Coal and Steel Community and culminating in the European Union — that was explicitly intended to prevent a return to the bloodlettings of the past.

The point is that we do not really know why the past 60 years have been more peaceful than the decades that preceded them, but U.S. leadership was probably only one factor among several.

Furthermore, this peaceful “world order” was actually quite limited in scope and hardly covered the entire globe. As American historian Andrew Bacevich makes clear, the pacifying effects of U.S. leadership did not prevent costly wars in Korea or Indochina, did not prevent India and Pakistan from fighting in 1965 or 1971, and did not stop millions of Africans from dying in recurring civil and international wars. The United States did help end the brief Middle East wars in 1956, 1967, and 1973, but it did little to prevent them from breaking out and didn’t get serious about genuine peace efforts until it helped broker the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty in the 1970s. Washington did nothing to stop the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), and U.S. leaders actively fueled conflicts in Central America and Southern Africa when they seemed to serve broader strategic purposes. U.S. aid to the Afghan mujahideen may have helped bring the Soviet Union down, but it also helped wreck Afghanistan and gave birth to the Taliban and al Qaeda. More recently, American “leadership” has produced failed states or worse in Iraq, Libya, Yemen, and Somalia. As an agent for peace, in short, the United States has a decidedly mixed record.

We should be equally cautious in crediting America with the past six decades of economic growth. To be sure, the original Bretton Woods institutions performed reasonably well in their day, and U.S. support for trade liberalization helped reduce global tariffs and fueled the post-World War II recoveries. But U.S. “leadership” of the world economy was hardly an unbroken string of successes: U.S. Middle East policy helped cause the punishing oil crises of the 1970s, and the 2008 financial crisis from which the world economy is still recovering began right here in the United States.

My point is not that the U.S. role in the world has been consistently negative; the point is that those who believe U.S. leadership is the primary barrier to a return to anarchy and barbarism are overstating America’s positive contributions. It is far from obvious, for example, that the United States needs to garrison the world in order to maintain a healthy U.S. economy, because it is free to trade and invest wherever profitable opportunities arise. Or as Dan Drezner has noted: “The economic benefits from military predominance alone seem, at a minimum, to have been exaggerated in policy and scholarly circles.”

But if defenders of American hegemony give U.S. leadership too much credit, some critics of U.S. foreign policy make the opposite error. I’m often critical of U.S. foreign policy — and especially its overreliance on military force, indifference to the deaths it causes, self-righteous hypocrisy, and refusal to hold officials accountable — but my criticisms pale in comparison to those offered up by the extreme left and extreme right and by many foreign opponents. Blaming all the world’s ills on the United States is not merely factually wrong; it lets the real perpetrators off the hook.

For example, though it is clear that unthinking U.S. support has sometimes enabled allies to misbehave in various ways, these states acted as they did for their own reasons and not because they were following Washington’s orders. The United States did not want Pakistan to develop nuclear weapons or back the Taliban, for example, and it does not want Israel to keep expanding settlements or pummeling Gaza for no good reason. Nor did Washington want Saudi Arabia to spend millions of dollars spreading Wahhabi ideology or want other key allies to sign up for China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. U.S. leaders did not do all they could to stop these (and other) activities, but even a global superpower cannot control everything its allies do.

Similarly, the United States did not launch the uprisings against Muammar al-Qaddafi or Bashar al-Assad, did not start the long civil conflict in Yemen, and cannot be blamed for the Sunni-Shiite divide that is now polarizing the Middle East. The financial meltdown on Wall Street may have triggered the euro crisis, but the United States is not responsible for the foolish decision to create the euro in the first place, and Washington didn’t tell the Greek government to cook its books or tell German banks to make foolish loans. The Turkish, Polish, and Hungarian governments aren’t drifting toward authoritarianism today because Washington encouraged them, and they will almost certainly chart their own course no matter what U.S. leaders advise.

Instead of seeing the United States as all-powerful and either uniquely good or evil, therefore, it makes more sense to see it as pretty much like most past great powers. It has done some good things, mostly out of self-interest but occasionally for the benefit of others as well. It has made some pretty horrific blunders, and these actions had significant repercussions. It has done bad things for the usual reasons — overconfidence, ignorance, excessive idealism, etc. — and, to paraphrase Bill Clinton, “just because it could.”

As I’ve noted in the past, U.S. foreign policy works best when it puts diplomacy first and views the use of force as a last resort. Its military power is often very effective at deterring large-scale aggression and especially when vital U.S. interests are obviously engaged. As the 1991 Gulf War showed, the United States can also be effective at reversing aggression, especially when it combines force and diplomacy and has clear and feasible political goals. The United States can sometimes promote human rights and other liberal values, but success is more likely when the United States is patient and works in tandem with local forces (as it did in South Korea, the Philippines, or Myanmar). When Washington tries to do social engineering at the point of a gun — as in Iraq, Afghanistan, and a few other places — the results are not pretty.

And what worries me — and should worry you, too — is that neither Hillary Clinton nor Donald Trump appears to get this. Clinton remains an unapologetic liberal interventionist, whose judgment has frequently led her astray but who appears to have learned little from the experience. Trump, on the other hand, is a modern-day descendant of the 19th-century “Know-Nothings,” a man who seems unconcerned by his own ignorance and who probably thinks Triumph the Insult Comic Dog would make a good U.N. ambassador. Given that there are more than 150 million native-born Americans over the age of 35 (and thus eligible to be president), it’s depressing to think our choices — realistically speaking — are coming down to this.

Source: Foreign Policy