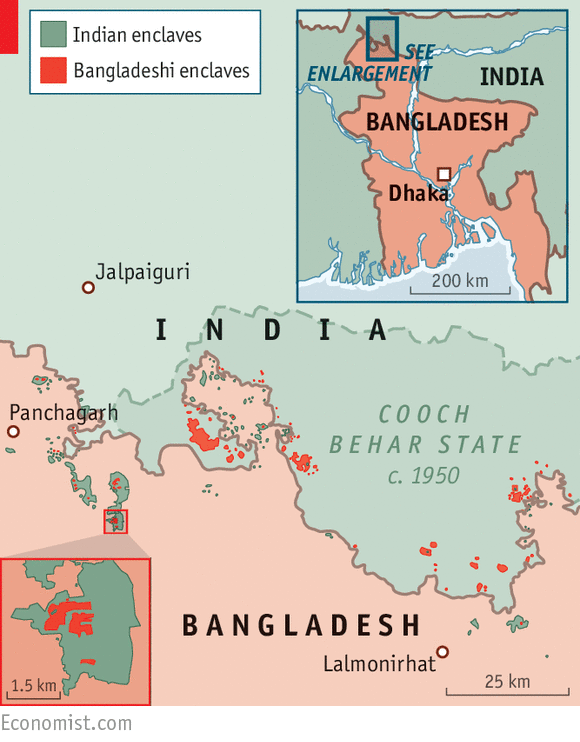

THIS year marks a watershed in the annals of bizarre geography. On July 31st India and Bangladesh will exchange 162 parcels of land, each of which happens to lie on the wrong side of the Indo-Bangladesh border. The end of these enclaves follows an agreement made between India and Bangladesh on June 6th. The territories along the world’s craziest border include the pièce de résistance of strange geography: the world’s only “counter-counter-enclave”: a patch of India surrounded by Bangladeshi territory, inside an Indian enclave within Bangladesh. How did the enclaves come into existence?

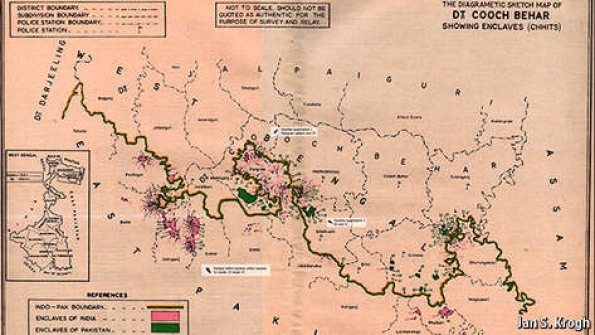

India and Bangladesh share a 4,100km (2,500-mile) border, hastily drawn around one of the most densely populated places on earth in 1947. Because of endless zigging and zagging it constitutes the world’s fifth-longest. The parcels to be exchanged are 111 Bangladeshi and 51 Indian enclaves clustered on either side of Bangladesh’s border with the district of Cooch Behar, in the Indian state of West Bengal. The enclaves are invisible on most maps; most are invisible on the ground too. But they became an evident problem for their 50,000-odd inhabitants with the emergence of passport and visa controls. Independent India and Bangladesh—part of Pakistan until 1971—each refused to let the other administer its exclaves, leaving their people effectively stateless.

Legend has it that the enclaves were formed as a result of a series of chess games played between two maharajas centuries ago (the chunks of land were used as wagers). They were later attributed to a drunken British officer who supposedly spilt drops of ink on the map when drawing the India-Pakistan border in 1947. According to Reece Jones, a political geographer, the plots were cut from larger territories by treaties signed in 1711 and 1713 between the maharaja of Cooch Behar and the Mughal emperor in Delhi, bringing to an end a series of minor wars. Armies kept the territory they controlled, inhabitants paid taxes to their respective feudal rulers and people moved freely across a quiltwork patterned by feudal warfare. Fifty years later, efforts by the British East India Company to clear up the messy map failed when their residents opted to stay put.

It was partition, the division of India and Pakistan, that turned the enclaves into a no-man’s-land. The Hindu maharaja of Cooch Behar chose to join India in 1949 and he brought with him the ex-Mughal, ex-British possessions he inherited. Enclaves on the other side of the new border were swallowed (but not digested) by East Pakistan, which later became Bangladesh. It was not until 1974 that the two countries first agreed to fix this zany borderland. India agreed to forgo compensation for a net loss of territory that is roughly half the size of Hong Kong Island (or 2,000 cricket stadiums). But weak governments and nationalism thwarted India’s progress. In May 2015, 41 years later, its parliament finally passed a constitutional amendment required to cede land to Bangladesh and resolve the anomaly.

Erasing the enclaves will have three main effects. The first will be felt primarily by residents, who can now choose which country to join, acquiring basic benefits of citizenship in the process. The process will allow India and Bangladesh to focus on weightier matters. Finally, in vanishing from the borderlands of Bengal, the world’s enclaves have taken a flying leap towards extinction. From this summer, there will be 49 extraterritorial patches left anywhere, mainly in western Europe and on the fringe of the former Soviet Union. Most of the world’s enclaves will have disappeared overnight.

Source: The Economist