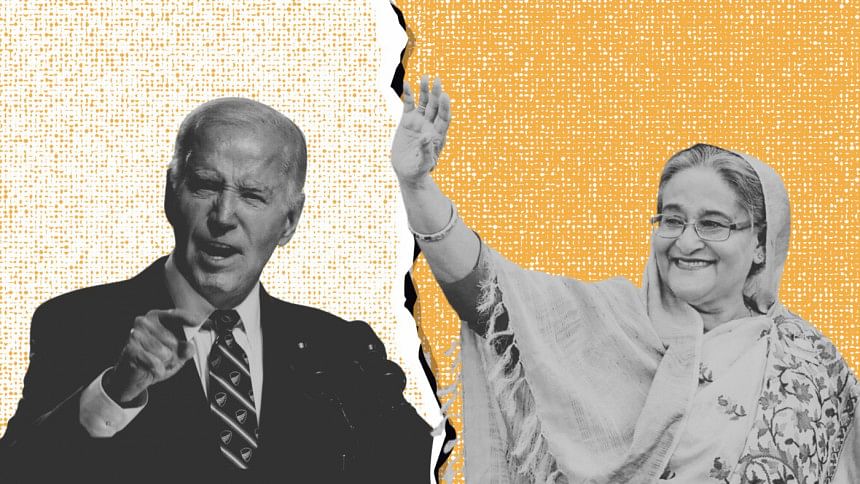

When the US State Department declared, on January 8, that Bangladesh’s elections the day before “were not free or fair,” it was indirectly acknowledging a major policy setback.

For many months, the Biden administration used Bangladesh as a test case for its values-based foreign policy. It advocated tirelessly for greater respect for human rights, for democratic principles, and especially for free and fair elections. It deployed various tactics—relentless public messaging, meetings with political party leaders, written appeals for different political parties to work out differences, and sanctions and visa restrictions.

It’s unclear why the administration chose to pursue its democracy agenda so robustly in Bangladesh (and it should be noted that this agenda was also pursued, albeit less emphatically, during the Trump administration). One reason may have been a strong expectation of success: unlike some other countries where the US has sought to promote democracy, Bangladesh does have a legacy of democratic institutions and achievements—meaning it shouldn’t be as heavy a lift to advocate for something with a precedent. US officials have also been heartened by the reductions in RAB abuses since Washington sanctioned it in 2021.

But the State Department’s assessment concedes its policy fell short. So why, despite all its efforts, was the election—in Washington’s own view—marred by violence, crackdowns on the opposition, and irregularities?

The question now is what next for US policy? Will Washington deploy harsher tactics that it believes may better incentivise Bangladesh’s government and broader political class to slam the brakes on a slide toward authoritarianism? Or will the US dial it down, and take a softer approach to democracy promotion? Alternately, will it jettison its values-based approach altogether and replace it with an interests-based lens? Or will it try for a middle ground that balances both approaches?

Washington’s next moves will be shaped by two key considerations: Its assessment of the degree to which the AL hindered free and fair elections, and its future goals for its relationship with Bangladesh.

The administration will examine the extent of AL-perpetrated irregularities and election-related violence. How it evaluates the BNP boycott will also be critical. Will Washington put more weight on the boycott itself (which would emphasise the BNP’s stubborn refusal to participate in an election not overseen by a neutral government), or on the broader factors that drove the boycott (especially the non-level playing field generated by the AL’s relentless crackdowns on the BNP)? If more weight is given to the latter, there are higher chances of muscular US policy responses. The State Department has laid out additional signposts, calling on Dhaka “to credibly investigate reports of violence and hold perpetrators accountable. We also urge all political parties to reject violence.” Washington will be watching on these fronts, too.

However, even if the administration renders the harshest possible judgement on AL complicity in an unfree and unfair election, that doesn’t guarantee harsh US responses. And this gets to the matter of Washington’s objectives for the broader US-Bangladesh relationship.

Amid all the attention on bilateral tensions over democracy and elections, it’s easy to forget that US-Bangladesh relations have actually strengthened considerably in recent years. The US is the top destination for Bangladesh exports, and the biggest source of FDI in Bangladesh. In 2020, the two sides announced a new vision for boosting economic cooperation in areas ranging from tech collaborations and air travel to blue economy initiatives and energy security. Commercial cooperation has been further energised by the launching of the US-Bangladesh Business Council, part of the US Chamber of Commerce, in 2021.

Additionally, over the last decade or so, US officials have started to invest in Bangladesh with more strategic significance. The origins of this shift may lie in the scholarship of influential American foreign policy analysts, most prominent among them Robert Kaplan, which highlights the importance of the Indian Ocean Region for US interests. In recent years, going back to the Trump era, Bangladesh has been emphasised in multiple Indo-Pacific strategy documents published by the Pentagon and State Department, with emphasis on potential for cooperation on counterterrorism, counter piracy, counternarcotics, and maritime issues.

Intensifying great power competition has made Bangladesh’s strategic significance come into even sharper relief in Washington. Consider China’s deepening influence in the Indian Ocean Region: Its military base in Djibouti, its ships’ presence from the Bay of Bengal to the Andaman Sea, and of course its deepening ties with Dhaka and backing for Bangladesh’s first submarine base. Meanwhile, witness Russia’s intensifying engagement with Dhaka. Unsurprisingly, US officials now call Bangladesh a strategic partner.

Consequently, US-Bangladesh relations have been busy in recent years: High-level diplomatic engagements, military exercises, business leader delegation visits, and extensive US humanitarian assistance—from support for Rohingya refugees to pandemic assistance. Washington is the top supplier of humanitarian aid for the Rohingya crisis, and it has provided more COVID-19 vaccines to Bangladesh than to any other country.

Given this expanding partnership, Washington will want to avoid leaning too heavily on the tensions-prone values-based aspect of bilateral ties—because that risks damaging the relationship. It will likely look to balance the values- and interests-based dimensions of its relations with Dhaka.

But that will be a delicate balance.

Washington needs diplomatic space with Dhaka to try to push back against Chinese and Russian influence in Bangladesh. But that space shrinks if Bangladesh is pushed into a corner with tough trade sanctions. Previous punitive US tactics—visa restrictions, RAB sanctions, suspensions of GSP benefits—weren’t as harmful to bilateral ties because those measures weren’t as damaging for Bangladesh on the whole.

On the other hand, Bangladesh’s democratic backsliding constrains efforts to expand cooperation. Dhaka’s crackdowns on Internet freedom may deter prospective US tech investors. Bangladesh’s poor labour rights record precludes the International Development Finance Corporation—Washington’s main investment arm in the Indo-Pacific—from sponsoring infrastructure projects. And if Bangladesh’s security forces ramp up abuses, America’s Leahy law—which bans US assistance to foreign militaries implicated in serious human rights violations—could kick in, jeopardising deeper military cooperation.

In the coming weeks, expect a reoriented US focus away from elections and more toward promoting rights and democracy in Bangladesh more broadly—though more visa restrictions are possible for those that hindered free and fair polls. Meanwhile, the administration, impelled by commercial and strategic interests, will continue to push for deeper partnership.

Bangladesh will remain a test case for Washington’s values-based foreign policy. But so long as it keeps bumping up against the relationship’s strategic imperatives, the experiment could grow increasingly untenable in a world order where realpolitik so often prevails.

Daily Star