Rarely have 250 words been so important – five short, obscure paragraphs in a European treaty that have suddenly become valuable political currency in the aftermath of Britain’s decision to leave the EU, the Guardian reports.

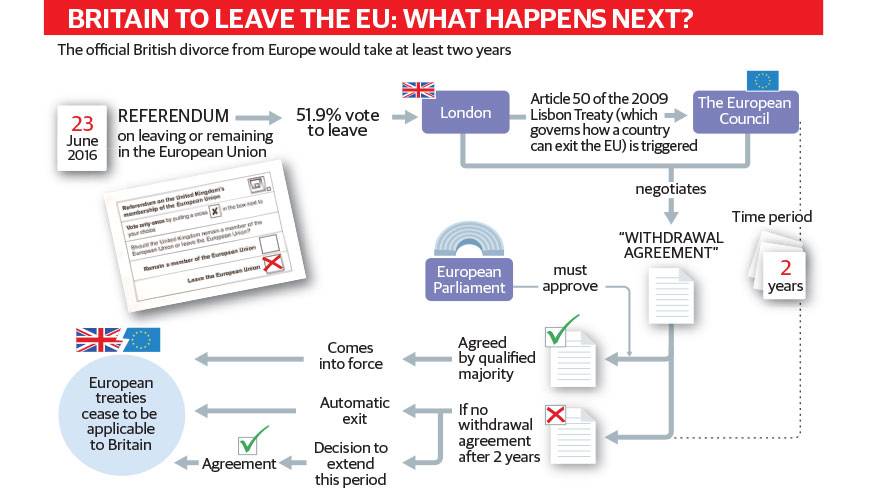

Article 50 of the Lisbon treaty sets out how an EU country might voluntarily leave the union. The wording is vague, almost as if the drafters thought it unlikely it would ever come into play. Now, it is the subject of a dispute between EU leaders desperate for certainty in the wake of the Brexit vote, and Brexiters in the UK playing for time.

Article 50 says: “Any member state may decide to withdraw from the union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.”

It specifies that a leaver should notify the European council of its intention, negotiate a deal on its withdrawal and establish legal grounds for a future relationship with the EU. On the European side, the agreement needs a qualified majority of member states and consent of the European parliament.

The only real quantifiable detail in the article is a provision that gives negotiators two years from the date of article 50 notification to conclude new arrangements. Failure to do so results in the exiting state falling out of the EU with no new provisions in place, unless every one of the remaining EU states agrees to extend the negotiations.

No country has ever invoked article 50 – yet.

When could it happen?

Britain’s Brexit vote does not require the government to pull the trigger immediately because the referendum is not legally binding. Indeed, how and when to notify has become the main tactical dispute in the hours that have followed Thursday’s vote.

In his resignation speech, David Cameron made it clear he was in no hurry to push the button. “A negotiation with the European Union will need to begin under a new prime minister and I think it is right that this new prime minister take the decision about when to trigger article 50 and start the formal and legal process of leaving the EU,” he said.

As such, he has done a favour for the people who did most to unseat him – Boris Johnson and Michael Gove. Both have argued there should be no hurry to pull the trigger: doing so would set the clock ticking, putting Britain at a negotiation disadvantage at a time when its political class is in disarray.

But there is strong pressure from two quarters to get the ball rolling. Ukip sees no reason for delay, with party leader Nigel Farage calling for action “as soon as humanly possible”. Perhaps more importantly, European leaders, frustrated, angry and hugely disappointed in Britain’s self-imposed exodus, want matters resolved smartly to keep uncertainty to a minimum and prevent exit contagion from spreading.

The German foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, said on Saturday after meeting counterparts from the five other EU founding states: “We say here together that this process must start as soon as possible.” Earlier, Jean-Claude Juncker, the EU commission president, said: “It doesn’t make any sense to wait until October to try and negotiate the terms of their departure. I would like to get started immediately,” he said.

What can the EU do?

But however much Europeans want to accelerate the process, there are scant legal means to jump-start it.

Kenneth Armstrong, professor of European Law at Cambridge University said: “There is no mechanism to compel a state to withdraw from the European Union. Article 50 is there to allow withdrawal, but no other party has the right to invoke article 50, no other state or institution. While delay is highly undesirable politically, legally there is nothing that can compel a state to withdraw.”

The only card the EU does hold is another article of the Lisbon Treaty – but it’s a big card, an ace. Under Article 7, the EU could suspend a member if it deems it to be in breach of basic principles of freedom, democracy, equality and rule of law.

But Nikos Skoutaris, lecturer in European Union law at the University of East Anglia said: “To trigger article 7, there must be a reason to do with the foundational values of the EU, democracy and the rule of the law on so on. It has never been used. There have been occasions when there have been threats to use it, in the 1990’s when there was a possibility of neo-Nazis being in an Austrian coalition.

“There has been some discussion of it relation to Poland and Hungary recently, but it is very difficult to see this applied to the UK. I don’t think the European Union would use what is considered a nuclear weapon.”

What would happen next?

Once the article 50 trigger is pulled, the EU council of ministers will by qualified majority voting agree a negotiation mandate, in the form of directives to the commission.

They will have to agree on the terms for divorce, essentially a set of instructions and red lines for the European commission, which would be in charge of managing talks. The process is designed to give the EU the upper hand over the departing state, according to Andrew Duff, a former Liberal Democrat MEP, who helped devise article 50. “We could not allow a seceding state to spin things out for too long. The clause puts most of the cards in the hands of those that stay in.”

The full scale of the task facing Whitehall will become clear. The UK will have to renegotiate 80,000 pages of EU agreements, deciding those to be kept in UK law and those to jettison. British officials have said privately that nobody knows how long this would take, but some ministers say it would clog up parliament for years.

As has been wryly noted already, there is only one precedent to refer to here. Greenland left the EU in 1985 after two years of negotiation. It has a population of 55,000, and only one product: fish.

Source: Dhaka Tribune