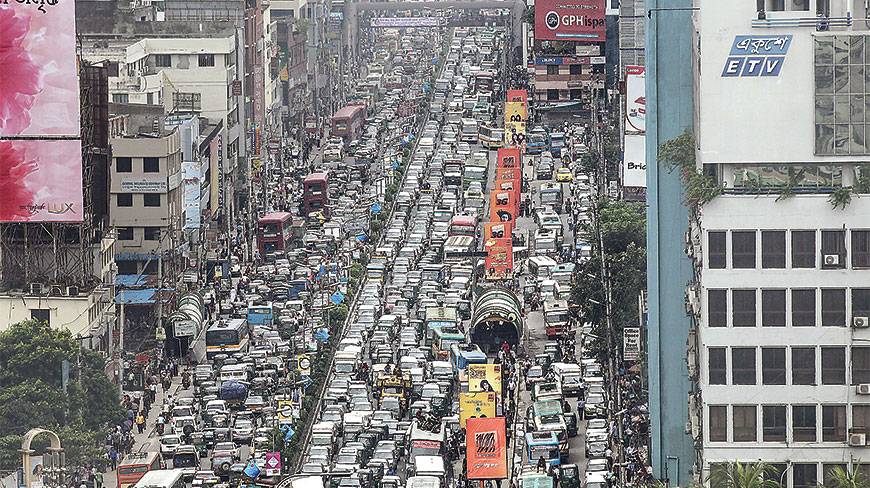

Traffic jams, fender benders, fatalities, emissions, expense of delay, and social marginalisation … these are all direct and indirect costs of a motorist-dependent city. And Dhaka is such an urban complexity that has exploded in population size and density, a socioeconomic intricacy, and is reliant on movement via cars. This can be seen by the astronomical number of single-passenger vehicles on the roads.

Car dependence has historically shaped the way that cities are planned, and Dhaka is not exempt. Car dependence means wider roads, more congested roads, and limited green space and walkways.

Cars make up a higher vehicle mix and move fewer people. Cars can stimulate economies, but can also impair them. Cars consume otherwise economically and socially profitable space. Here is a simple image for your consideration: The average length of a car is just over 4 metres.

The average length of a passenger bus is just over 12 metres (three times the length of a car). The total number of passengers allowable in an average sized car is four plus one driver, who may or may not be a passenger; for this visual we will assume not.

The number of passenger seats in an average sized bus is 28. Therefore, although buses take up three times more road space per unit, they can transport seven times (or more) passengers. So, for fully occupied cars to move 1,000 people, they would take up 1,000 metres of road space or one metre per person. For buses to transport the same number of seated people, it would take up less than half (42.86%) the road space of cars.

Before delving into this further, please understand that this is not an argument to make Dhaka exclusively car-free, nor is it a fully comprehensive review; this is a basic argument to encourage improved public transit facilities, particularly bussing, to give a glimpse at some benefits of public transit, eliminate the stigma of public transportation use, and to discourage sole dependence on single-passenger vehicles in Dhaka.

The environment … it is obvious that more vehicles contribute more emissions that result in higher particulate levels in the air. It is estimated that the number of vehicles have been increasing at a steady rate of 10% annually in Dhaka. This rate of increase has resulted in a 5-6% increase in each of various types of emissions, including carbon monoxide, particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and hydrocarbons.

Increased air pollution is hazardous to health and destructive to infrastructure due to decay induced from chemically altered air quality. Air pollution increases urban runoff which affects waterways, agriculture, landscapes, and increases erosion and deterioration of earth bankings and roads.

The society: In Dhaka, as with many other cities among developing and developed nations, public bussing has a socioeconomic stigma toward riders. Use of public buses is often associated with poverty or inability to purchase a vehicle or lack of ability to operate a vehicle. Here, where many vehicles are not self-driven and the buses are in poor repair, the stigma can be exacerbated. This stigma is validated globally, based on the racial and income data of riders; but there is slowly an emerging shift in paradigm that can be and should be embraced here as well.

Other social costs that cars impose relate to the overall restrictions to city design due to the need for more (or wider) road space. Car-dependent cities often do not support pedestrian requirements for safety and access. Furthermore, green space can be limited due to the need for more road space and lack of parking facilities. Recreation and exercise is therefore compromised.

The economy: It is true that cars can help the economy. Vehicle taxes and associated registration costs are extremely high, but the abuse of roadways due to the high traffic flows in Dhaka creates a development challenge for improving and even maintaining infrastructure within limited financial resources.

Car subsidies exist here, even in an informal and unintentional context; parking and road use is more or less free. Cars that park on street shoulders and in traffic lanes incur costs to movement and design. The congestion from the abundance of cars on the roads creates economic burdens and the planning that is directly attributed to facilitating car dependency, limits other income sources. A past study showed that the vehicular congestion of Dhaka city resulted in an annual cost of over $18.1bn due to the delay (UNDP).

A solution: Following global trend of promoting improved public transport, Dhaka city can identify major causeways that are limited for car use; this can be implemented by days, hours, or without specification. Car related fees can eliminate unintended subsidies for car users.

Public bus infrastructure can become a key focal point for government expenditure; better buses, the existence of bus lanes, and more attention to improving ridership and rider safety and comfort. The government of Bangladesh and associated organisations such as John McAslan + Partners, JICA, and consultants who have been tasked with the development of the Dhaka Metro must consider the impact on the overall transportation dynamic.

This means that to motivate metro users, considerations must be made to improve bussing within the stop locales. Car parking at major stations may be incorporated, but land space is valuable; so bussing to and from stations for metro riders must be a complementary strategy in the metro project.

As Dhaka, and Bangladesh, continue positive growth and development, understanding the challenges of urban realities is critical. Recently, seven international cities have been identified due to their diminishing dependence on cars (fastcoexist.com; Adele Peters).

Internationally, governments and the public are gaining understanding that car dependency in cities is becoming more of a downfall for sustainable and social development and a hindrance to urban planning and design.

Source: Dhaka Tribune