By Trevor Aaronson

In 2011, a sex offender and onetime jihadi wannabe helped snare a suspected terrorist—and was promised $100,000 in return. In the sordid world of FBI informants, that’s the price of doing business.

On an otherwise ordinary night in May 2011, Robert Childs realized his friend, Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif, might be on the verge of becoming a terrorist. The two men, who attended a Seattle mosque together, ate fried chicken at Abdul-Latif’s small apartment with his wife and young son. Afterward, Abdul-Latif walked Childs to the dimly lit parking lot outside his building, where his guest’s orange 1979 Chevy Suburban was sitting. There, he posed a startling question: Could Childs help him get some guns?

Abdul-Latif said he wanted to carry out an attack inspired by the 2009 shooting at Fort Hood, in which Army Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan killed 13 people. But unlike Hasan, who acted alone, he was looking for associates. “I already have a guy that wants to do it, if you want to come in with it,” Childs recalls Abdul-Latif saying.

A skinny white man with close-cropped brown hair, Childs, then 35, had previously boasted to Abdul-Latif about his skill with guns. His father had been a Marine, and Childs had trained with pistols and rifles at a military boarding school. By contrast, 33-year-old Abdul-Latif, who kept his black scalp shaved and beard full, had limited experience with firearms. He’d once held up a 7-Eleven with two plastic toy guns and had served three years in prison for the robbery.

Hoping to drive away quickly, Childs told me, “I didn’t give him a yes or no that night.” He wasn’t going to help his friend, but he was worried about the startling request nonetheless. What if Abdul-Latif committed a crime with guns he got elsewhere? Could Childs be implicated for not informing police about their conversation? A convicted rapist and child molester, Childs had already served three stints behind bars—a total of nine years. Recently released, he was trying to turn over a new leaf.

Childs set up a meeting with Samuel DeJesus, a detective with the Seattle Police Department (SPD) and told him about the encounter. According to Childs, DeJesus asked him whether he would help authorities build a case against Abdul-Latif. “What do you want in return?” DeJesus added. “I wanted my whole record wiped off,” Childs recollects. The SPD, he claims, gave him the impression it could make that happen. (DeJesus declined to comment for this article.)

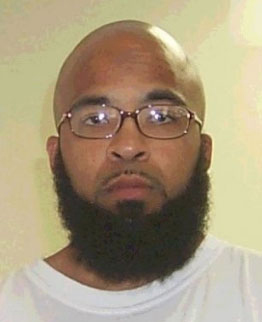

Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif (top) and Walli Mujahidh (bottom).

Within a matter of days, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) entered the picture. Abdul-Latif had popped up on the bureau’s radar after he posted several videos on YouTube that April and May, showing him criticizing Western society and insisting that peace could never be made with non-Muslims. When the FBI learned about Childs’s information, a result of the SPD’s involvement in a joint homeland security effort with the bureau, agents met with him and said they would be working on the case. Childs was happy to oblige the power move. “If you can’t trust the FBI,” he reasoned, “who can you trust?” And so he became part of the FBI’s post-9/11 counterterrorism apparatus; comprising more than 15,000 informants, it is the largest domestic spying network in U.S. history.

Childs began wearing recording equipment when he met with Abdul-Latif. On June 14, 2011, the FBI gave him a cache of weapons—a grenade, assault rifles, and handguns—that he showed to Abdul-Latif in the back of a car. Childs demonstrated how to switch out magazines and chamber a round. When Childs removed the grenade from a duffel bag, Abdul-Latif seemed amazed. “For real?” he asked, according to an FBI affidavit. “If you throw it, it will blow up?” Pull out the pin, Childs explained—then throw.

A week later, on the evening of June 22, Childs, Abdul-Latif, and a third man, Walli Mujahidh, met at a chop shop to discuss plans to storm the Seattle Military Entrance Processing Station, where fresh-faced Army enlistees report to duty for the first time. (“They are being sent to the front lines to kill our brothers and sisters,” Abdul-Latif had said a few days earlier in a conversation caught on Childs’s recording device.) As Childs was showing his companions how to use FBI-provided M16 assault rifles, the bureau pounced: Agents threw a stun grenade and stormed the room. Abdul-Latif and Mujahidh were arrested.

Although he wasn’t named publicly, Childs was immediately held up as an American hero. “But for the courage of the cooperating witness, and the efforts of multiple agencies working long and intense hours,” Laura Laughlin, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Seattle office, said in a news release the day after the operation, “the subjects might have been able to carry out their brutal plan.”

Today, Abdul-Latif and Mujahidh are serving 18 and 17 years, respectively, for conspiracy to murder officers and agents of the United States and conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction. But serious questions have emerged about whether, had it not been for the FBI’s efforts, the two ever would have gotten their hands on the means to commit serious crimes. According to local media and the men’s attorneys, Abdul-Latif had a history of mental problems and attempting suicide. Not long before the bust, he had filed for bankruptcy protection. Mujahidh was a penniless drifter diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and bipolar tendencies who had done 12 stays at psychiatric hospitals. In other words, they were arguably among the “fragile human beings” whom, according to Karen Greenberg of the Center on National Security at Fordham University’s School of Law, the FBI often targets in stings.

Meanwhile, Childs’s “courage” has been all but forgotten. He says he was paid handsomely for luring Abdul-Latif and Mujahidh, but his criminal record was never expunged. He now lives more than 3,000 miles from Seattle, in Key West, Florida; he is homeless, riding a bicycle around town and sleeping in a secluded spot of mangrove forest near U.S. Highway 1. “I feel just as much a victim of the FBI as Abdul-Latif,” Childs says, smoking a cigarette one afternoon in March 2015 at an outdoor table at a pizza restaurant. He wears a state-provided ankle monitor—a tangible reminder that he is a sex offender.

In the domestic war on terror, the front lines are often manned by unsettled—or unsettling—figures like Childs, criminals and hustlers commissioned by the FBI to pursue equally problematic or susceptible targets. And while the informants hope that their assignments will put money in their pockets, erase their troubled pasts, or both, in many cases the bureau cuts off contact when operations are over.

To protect the homeland, in other words, the FBI exploits bad guys to catch what it claims are worse ones. It’s a dirty 21st-century spy game aptly summarized by a popular saying at the bureau: “To catch the devil, you have to go to hell.”

After the intelligence failures of 9/11, the White House told the FBI that there should never be another attack on U.S. soil. The bureau’s mission was to find the terrorists before they struck. Al Qaeda, in turn, knew it wouldn’t be easy to again send actors into the United States to launch a coordinated attack. Instead, it moved to what FBI officials describe as a “franchise model”: using online avenues to encourage young Muslims in the West to commit violence. Law enforcement officials view the Fort Hood shooting as a realization of this model. Prior to the attack, Hasan had exchanged emails with Anwar al- Awlaki, the U.S.-born cleric known for posting videos on YouTube advocating violence against America and for masterminding al Qaeda’s slickly designed online magazine, Inspire. (Awlaki was killed in a 2011 drone strike in Yemen.)

Concerns about franchise operations have made American-bred “lone wolf” terrorists the FBI’s new focus. Agents want to catch them just as they make the leap from sympathizer to potential attacker, so the bureau has recruited informants to infiltrate Muslim communities nationwide. Their task: gather information on men who seem interested in violence. Critics, however, allege the intelligence net has been cast even wider. In 2011, the American Civil Liberties Union brought suit against the FBI for instructing an informant in Southern California “not to target any particular individuals they believed were involved in criminal activity, but to gather as much information as possible on members of the Muslim community, and to focus on people who were more devout in their religious practice.”

In many cases, the FBI has directed informants to pose as terrorists and to provide both the means—weapons, for instance—and opportunities for targets to participate in plots. Arrests often follow: According to Human Rights Watch, nearly half of the more than 500 terrorism-related cases brought in federal courts between Sept. 11, 2011, and July 2014 involved informants, and about 30 percent placed informants in roles where they actively helped foment terrorism schemes.

Rights activists have accused the FBI of using informants to manufacture terrorists in order to demonstrate the bureau’s effectiveness and justify its $3.3 billion annual counterterrorism budget. Human Rights Watch has noted that investigations “have targeted individuals who do not appear to have been involved in terrorist plotting or financing at the time the government began to investigate them” and that some efforts have been aimed at “particularly vulnerable individuals (including people with intellectual and mental disabilities and the indigent).”

Among these individuals is James Cromitie, a broke Wal-Mart employee with a history of mental problems whom an FBI informant offered $250,000 to bomb synagogues and shoot down military supply planes in New York. Another informant convinced Rezwan Ferdaus, a young American of Bangladeshi background, to engage in a plot to bomb the Capitol. When he was arrested, Ferdaus was being treated for mental illness. FBI agents tracking Sami Osmakac—a Kosovo-born man with schizoaffective disorder now serving 40 years for planning attacks in Tampa, Florida—were caught on record describing him as a “retarded fool” whose aspirations to commit violence were “wishy-washy.”

The FBI isn’t just taking advantage of its targets’ vulnerabilities, however. It is also capitalizing on informants’ weaknesses and, in many cases, turning a blind eye to their own crimes. When he started working for the bureau, Shahed Hussain, the informant in the Cromitie case, had been convicted of fraud for providing driver’s licenses to illegal U.S. residents and was trying to avoid deportation to Pakistan, where he faced a murder charge. Hussain was paid $98,000 for spying and was also spared an indictment for bankruptcy fraud. The informant in the Ferdaus case, identified in court records only as “Khalil,” had a heroin habit and was caught shoplifting while wearing a wire. The man who spied on Osmakac, a Palestinian-American named Abdul Raouf Dabus, was facing foreclosure proceedings on his business and house in Florida when he worked for the FBI and was paid $20,000.

Other informants have included fraud artists, drug dealers, and a bodybuilder turned con man. A 2013 USA Today investigation found that the FBI allowed informants to break the law 5,658 times in a single calendar year. “It’s the irony of informants,” says James Wedick, a former FBI supervisory agent. “You can’t trust these guys.… But when we put these informants in front of judges and juries, we simply say, ‘You can trust him. He’s with us.’”

With his rocky criminal past, Childs fit right in among this inauspicious FBI crew.

Robert Childs was born in Indianapolis in 1976 to Jackie, a nurse, and Robert Sr., who had served in Vietnam. The two separated shortly after their son was born, and Childs lived with his father and stepmother, Mary Fleenor. According to both Fleenor and Childs, Robert Sr. was abusive. “He had beat me so bad, I could not sit down,” Childs recalls of one encounter with his father.

At 16, Childs set out on his own, winding up in California, where he says he earned his GED diploma. He later hitchhiked to the town of Issaquah, Washington. But he wasn’t there for long before getting into trouble: In October 1994, a woman contacted the police, alleging that Childs had raped her 14-year-old daughter. According to a statement made by the victim, Childs met the girl at a local arcade, went home with her, and forced himself on her while repeating the words, “It’ll be all right.” Childs was convicted and spent six months in jail, followed by a year on probation.

A second offense occurred not long after. In 1996, Childs, who by then was 20, met a 15-year-old girl at a mall in Seattle. According to police, the pair went to a park and fondled each other. The girl’s mother filed a report, and Childs later pleaded guilty to child molestation.

Back in prison, Childs befriended a white Muslim inmate and decided to convert. “[Islam] made sense to me at the time,” he says. He studied the Quran relentlessly: “When I do something, I go full blow.” He also admits to adopting a militant religious attitude. He avoided associating with anyone who wasn’t Muslim, and he and his new friends discussed atrocities committed against Muslims around the world, particularly in Chechnya, where Islamic fighters were resisting Russian control.

After he was released in 1998, Childs settled in Seattle and married a woman named Jo. He says he started a cleaning business and acquired clients that included a car dealership, dentist, and culinary school. Childs didn’t have employees, but he brought people on as independent contractors if he had more work than he could handle.

The FBI isn’t just taking advantage of its targets’ vulnerabilities, however. It is also capitalizing on informants’ weaknesses.

Sometimes, Childs gave jobs to Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif, whom he says he knew because the two men’s wives were friendly. Abdul-Latif didn’t have cleaning experience, but it didn’t matter: He was a Muslim. “It was about keeping business and money within the community,” Childs says.

In February 2007, Childs’s marriage was falling apart, and he decided to fulfill a long-held desire to fight for Islam. Being a mujahid, he believed, was the “highest plane” he could reach. Childs says he sold his business to Abdul-Latif and headed toward Chechnya, by way of Turkey. He wound up in the Turkish city of Malatya, where (to his surprise) he became friends with a German Christian missionary named Tilman Geske. But in April 2007, he says, tragedy struck: Geske and two other missionaries were tortured and killed by five Muslim men. According to media that covered the incident, a note left at the scene of the crime read, “This should serve as a lesson to the enemies of our religion. We did it for our country.”

Childs was distraught. He was no longer interested in fighting in Chechnya or anywhere else. “Do I want to be this person?” Childs considered. “Do I want to be known as a killer?”

When he returned to the United States, Jo was living in California, so Childs followed her there in hopes of repairing their marriage. But he was arrested for failing to register as a sex offender and spent three more years behind bars. Afterward, he made his way back to Seattle, where he started working at a dive shop. Although his religious fervor had waned, Childs attended a local mosque—and it was there, one day in early 2011, that he ran into his old friend Abdul-Latif.

Childs says his first meeting with the FBI took place in an industrial area of south Seattle, where police kept and maintained fleet cars. “The FBI interviewed me, questioned me about Abdul-Latif and his motives,” Childs says. When a deal to have his criminal record expunged came up, he claims “nothing was made out to be any different” from what it had been in his earlier conversation with the SPD’s DeJesus.

According to Childs, however, DeJesus approached him privately and urged him not to trust the bureau. The detective said the agents were interested in what the case could do for them, not in holding up their end of any bargain. “This case is what they call a career-maker,” Childs remembers DeJesus saying.

Childs dismissed the warning and recorded many hours of conversations with Abdul-Latif from June 6 to June 22, 2011. “If we gonna die, we gotta die taking some kafirs with us,” Abdul- Latif said at one point, referring to non-Muslims. Once Mujahidh, a friend of Abdul-Latif, was in the mix, Childs recorded him too. At dinner on June 21, Mujahidh asked about the plot to attack the military processing center: “So we are going in and killing everybody?” Childs said they would only kill anyone “in green” or with a military haircut. “This is my way of getting rid of sins, man,” Mujahidh said, according to government documents. “I got so many of ’em.”

Before the FBI raid, Childs told Abdul-Latif and Mujahidh that the site—the chop shop—was owned by a Muslim. He says that officials placed a Quran on a table inside the facility to make the story a little more believable.

After the arrests, Childs says he was congratulated on a job well done and was told to wait in an interrogation room at a Seattle law enforcement office. He recollects FBI agents coming in to give him updates—for instance, “Mujahidh is singing like a bird.” Childs was excited but also scared: “I do remember asking very specifically, ‘Nobody’s gonna know it was me, right?’”

Less than a week later, Childs says the FBI called him to set up a meeting. Agents picked him up at home and, inside a sedan with tinted windows, told him there was nothing they could do about his record. “You should be happy you did this as a citizen,” he recalls them saying. “That should be reward enough.” Childs claims DeJesus pressured the bureau to do better. At a subsequent meeting, agents told him they could offer money. Childs says they agreed on $100,000; a sentencing memorandum compiled by Abdul-Latif’s defense counsel describes Childs’s payoff as being approximately this amount. (The FBI declined to comment, citing a “longstanding policy of not commenting on sources, methods and techniques.”)

Childs says he wound up receiving $90,000 in installments over several months. But it quickly disappeared. A friend stole about $30,000 of the money, Childs claims, and he dropped another $20,000 on a boat and even more on a new Ford Excursion in which he installed expensive stereo equipment. “I got carried away,” he admits.

At the same time, Childs says he kept working as an informant with the SPD. He was gathering information on local anti-war protesters until one day his name and mug shot appeared in the Seattle Times, associated with the Abdul-Latif case. He suspects FBI agents leaked it because the money issue had made his relationship with the bureau tense.

“All of a sudden, my name goes everywhere,” Childs recalls. With information about his sex offenses in the news, he felt that the “hero” part of his identity went “completely out the window.”

Childs isn’t the first informant to feel abandoned by the FBI. Mohamed Alanssi, a Yemeni national, helped agents investigate Brooklyn’s hawaladars—underground Muslim money brokers—and Sheikh Mohammed Ali Hassan al-Moayad, who the bureau believed was raising funds for al Qaeda in New York. On Nov. 15, 2004, Alanssi faxed letters to the FBI in New York and to the Washington Post. He said his handler would not let him travel to Yemen to see his sick wife, and that he feared testifying as an informant would endanger his family. “Why you don’t care about my life and my family’s life?” Alanssi wrote in one of the letters. That afternoon, dressed in a suit soaked with gasoline, Alanssi set himself on fire outside the gates of the White House. Secret Service agents put out the flames, but not before 30 percent of his body had been burned.

In another case, Craig Monteilh—the bodybuilder turned con man, and the informant in the American Civil Liberties Union’s 2011 case—spent months spying on mosques while pretending to be a convert to Islam named Farouk al-Aziz. In December 2007, police in Irvine, California, charged him with stealing $157,000 from two women as part of a scam to buy and sell human growth hormone. Monteilh later claimed FBI agents instructed him to plead guilty in order to protect his cover; in exchange, the charges would eventually be removed from his record. In a 2010 lawsuit against the FBI, however, Monteilh alleged that the bureau reneged on its promises. He later dropped the suit after agreeing to what he terms a “confidential settlement.”

The FBI often seems quick to wash its hands of trouble that informants cause or allegations they raise. But no matter how murky or embarrassing an informant’s involvement in a case is, it rarely hampers an agent’s or handler’s career. Steve Tidwell, who supervised Monteilh’s operation, retired from the bureau and is now a managing director for former FBI Director Louis Freeh’s private security firm. There’s also former agent Ali Soufan, whose book about 9/11 and al Qaeda, The Black Banners, was a New York Times best-seller. Today, he runs a multinational private security company. One of the informants Soufan supervised was Saeed Torres, the subject of a new documentary, (T)ERROR, which won a Special Jury Award at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival. The movie depicts Torres, a former Black Panther and convict, as destitute and angry after being involved in sting operations that some critics have described as entrapment.

In one scene, Torres tells the filmmakers, “The government will use you, and they will drop your ass like a hot motherfuckin’ stone.”

After being exposed in the newspaper, Childs decided he couldn’t stay in the Pacific Northwest. He headed east, stopping briefly in Indianapolis to visit his stepmother, and then kept going until he reached Key West in October 2013. He rented a room and landed bartending gigs. In July 2014, however, the manager of a local Johnny Rockets restaurant told police that Childs, a former employee, had rung up five transactions totaling $863.11 on a stolen American Express card. Officers quickly realized Childs was a sex offender who hadn’t registered since arriving in Florida. When they arrested him, according to a police report, Childs claimed “he was hiding from a previous case he worked with detectives in Seattle, Wash.”

After learning of Childs’s arrest, DeJesus petitioned authorities to offer leniency. “For all intents and purposes, Robert Childs was a hero,” DeJesus wrote in an email to prosecutors, obtained from Florida authorities through an information request. Ultimately, Childs pleaded guilty to credit card fraud and no contest to failing to register as a sex offender. He agreed to be designated a “sexual predator,” was given time served, and got out of jail this January.

By then, his name had gotten around Key West—a small, gossipy town—and the room he’d been renting was no longer available. He says none of the bars on Duval Street, Key West’s main drag, would hire him. He claimed his address as under a highway overpass and started going to a Burger King almost daily to charge his ankle monitor.

When he began working for the FBI, Childs thought he was saddling up with white knights. That is no longer the case. “They get people who are vulnerable and desperate,” Childs says of the bureau’s informant program. “We are led to believe we can trust the FBI. I have no trust for them.… The public shouldn’t either.”

Trevor Aaronson (@trevoraaronson) is executive director of the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and is author of The Terror Factory: Inside the FBI’s Manufactured War on Terrorism.

Source: Foreign Policy