HOURS after the massacre in San Bernardino, Calif., on Dec. 2, and minutes after the media first reported that at least one of the shooters had a Muslim-sounding name, a disturbing number of Californians had decided what they wanted to do with Muslims: kill them.

The top Google search in California with the word “Muslims” in it was “kill Muslims.” And the rest of America searched for the phrase “kill Muslims” with about the same frequency that they searched for “martini recipe,” “migraine symptoms” and “Cowboys roster.”

People often have vicious thoughts. Sometimes they share them on Google. Do these thoughts matter?

Yes. Using weekly data from 2004 to 2013, we found a direct correlation between anti-Muslim searches and anti-Muslim hate crimes.

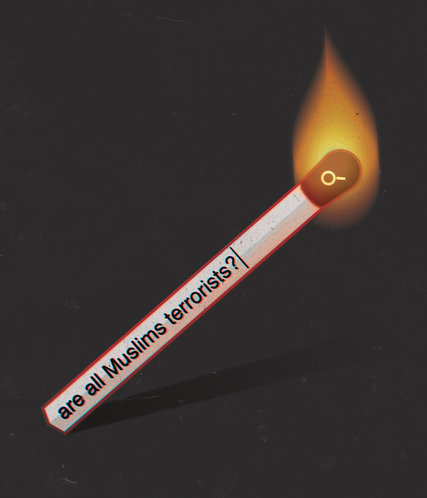

We measured Islamophobic sentiment by using common Google searches that imply hateful attitudes toward Muslims. A search for “are all Muslims terrorists?” for example leaves little to the imagination about what the searcher really thinks. Searches for “I hate Muslims” are even clearer.

When Islamophobic searches are at their highest levels, such as during the controversy over the “ground zero mosque” in 2010 or around the anniversary of 9/11, hate crimes tend to be at their highest levels, too.

In 2014, according to the F.B.I., anti-Muslim hate crimes represented 16.3 percent of the total of 1,092 reported offenses. Anti-Semitism still led the way as a motive for hate crimes, at 58.2 percent.

Hate crimes may seem chaotic and unpredictable, a consequence of random neurons that happen to fire in the brains of a few angry young men. But we can explain some of the rise and fall of anti-Muslim hate crimes just based on what people are Googling about Muslims.

The frightening thing is this: If our model is right, Islamophobia and thus anti-Muslim hate crimes are currently higher than at any time since the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks. Although it will take awhile for the F.B.I. to collect and analyze the data before we know whether anti-Muslim hate crimes are in fact rising spectacularly now, Islamophobic searches in the United States were 10 times higher the week after the Paris attacks than the week before. They have been elevated since then and rose again after the San Bernardino attack.

According to our model, when all the data is analyzed by the F.B.I., there will have been more than 200 anti-Muslim attacks in 2015, making it the worst year since 2001.

Continue reading the main story

Related in Opinion

How can these Google searches track Islamophobia so well? Who searches for “I hate Muslims” anyway?

We often think of Google as a source from which we seek information directly, on topics like the weather, who won last night’s game or how to make apple pie. But sometimes we type our uncensored thoughts into Google, without much hope that Google will be able to help us. The search window can serve as a kind of confessional.

There are thousands of searches every year, for example, for “I hate my boss,” “people are annoying” and “I am drunk.” Google searches expressing moods, rather than looking for information, represent a tiny sample of everyone who is actually thinking those thoughts.

There are about 1,600 searches for “I hate my boss” every month in the United States. In a survey of American workers, half of the respondents said that they had left a job because they hated their boss; there are about 150 million workers in America.

In November, there were about 3,600 searches in the United States for “I hate Muslims” and about 2,400 for “kill Muslims.” We suspect these Islamophobic searches represent a similarly tiny fraction of those who had the same thoughts but didn’t drop them into Google.

“If someone is willing to say ‘I hate them’ or ‘they disgust me,’ we know that those emotions are as good a predictor of behavior as actual intent,” said Susan Fiske, a social psychologist at Princeton, pointing to 50 years of psychology research on anti-black bias. “If people are making expressive searches about Muslims, it’s likely to be tied to anti-Muslim hate crime.”

Google searches seem to suffer from selection bias: Instead of asking a random sample of Americans how they feel, you just get information from those who are motivated to search. But this restriction may actually help search data predict hate crimes.

“Public polls, properly done, describe what a representative sample of Americans believe and feel about an issue,” Paul Sniderman, a political scientist at Stanford, explained in an email. “Google searches answer a different question: What do people excited enough by an issue to comment on it think and believe about it? The answer to this question, just because it is unrepresentative of the public as a whole, may be a better bet to predict hate crimes.”

It doesn’t take a representative sample to commit a hate crime. It takes one person. And many Muslim Americans have already experienced the havoc that one Islamophobe can create.

Asma Mohammed Nizami is a 23-year-old Muslim woman from Minnesota who directs services for students at a nonprofit and wears a head scarf, or hijab. Last Saturday, driving home from an event, she stopped at a traffic light, where she saw a man in the next car over glaring at her. He rolled down his window and called her a “Muslim bitch.” When Ms. Nizami started to drive away, he trailed her and then tried to run her off the road with his red Chevy Impala.

“It was terrifying,” said Ms. Nizami. “Ever since San Bernardino, I was scared someone would blame me, would react this way.” After the incident, she said, she ordered Mace spray and a dashboard camera from Amazon and wants to get her car windows tinted.

“It’s cold out here in Minnesota, so when I drive, I’ve started putting my hood up over my hijab,” Ms. Nizami said. “If I know someone can walk me to my car, I ask. It feels childish, but I ask.”

While the vast majority of Muslim Americans won’t be victims of hate crimes, few escape the “constant sense of fear and paranoia” that they or their loved ones might be next, said Rana Ibrahem, a Muslim woman from Long Island who works as a paralegal.

“When I see the hate crimes against mosques, I worry about my brother, who is bearded, and I worry about my mother, who wears the hijab,” said Ms. Ibrahem. “My mother tells me, ‘When I go to the supermarket now, I feel like everyone is staring at me, like I might be the object of their concern and fear.’ ”

What about the other side of the coin — compassion and understanding? Do they stand a chance against hate?

Searches for information about Islam and Muslims did rise after the attacks in Paris and San Bernardino. Yet they rose far less than searches for hate did. “Who is Muhammad?” “what do Muslims believe?” and “what does the Quran say?” for instance, were no match for intolerance. In the days following the San Bernardino attacks, for every American concerned with “Islamophobia,” another was searching for “kill Muslims.” While hate searches were about 20 percent of all top searches about Muslims before the attack, more than half of all search volume about Muslims became hateful in the hours that followed it.

It is not just that hatred against Muslims is extremely high today. It’s that it’s exceptional compared with prejudice against every other group in the United States.

We examined prejudicial searches against black people, white people, gay people, Asians, Jews, Mexicans and Christians. We estimate that negative attitudes against Muslims today are higher than prejudice against any group in any month since 2004, when Google began preserving detailed data on search volumes.

The search data also tells us that changes in Americans’ policy concerns have been dramatic. They happened, quite literally, within minutes of the terror attacks.

Before the Paris attacks, 60 percent of Americans’ searches that took an obvious view of Syrian refugees saw them positively, asking how they could “help,” “volunteer” or “aid.” The other 40 percent were negative and mostly expressed skepticism about security. After Paris, however, the share of people opposed to refugees rose to 80 percent.

Or consider searches related to mosques. For most of the past decade, the top searches for mosques expressed cultural curiosity — “what are mosques?” “what does mosque mean?” and “when do Muslims go to mosque?” But right after the San Bernardino shooting, searches about closing mosques, a once-unthinkable policy, surged to a sixth of Americans’ search volume about mosques.

I can understand how you purposely missed the Hate speech and Hate actions against Jews, Christians, Buddhists Hindus… Islamophobia my……

Love Teacher 2 minutes ago

As Decatur Winnipeg asks, “When’s the NY Times (or other prominent western news agencies) going to publish articles on how we combat this…

uofcenglish 2 minutes ago

I think it is really time for all Americans to look in the mirror. We are killing people treating our citizens like garbage, but, hey, let’s…

Unfortunately, there is not much evidence that some of the most obvious-sounding solutions might work. One idea might be to increase cultural integration. This is based on the “contact hypothesis”: If more Americans have Muslim neighbors, they will learn not to harbor irrational hate.

We did not find support for this in the data — in fact, we found evidence for the opposite. We looked at searches in the 10 counties with the highest Muslim populations in the United States. On average, these counties are about 11 percent Muslim, compared with 0.9 percent of the United States as a whole. We estimate, in these 10 counties, that anti-Muslim search rates are about eight times higher than they are in the rest of the country.

That’s evidence for the dominance of the “racial threat” hypothesis, which predicts that proximity breeds tension, not trust. John Sides, a political scientist at George Washington University, said, “This is one of the better chances for contact to work, and it doesn’t.”

Another solution might be for leaders to talk about the importance of tolerance and the irrationality of hatred, as President Obama did in his Oval Office speech last Sunday night. He asked Americans to reject discrimination and religious tests for immigration. The reactions to his speech offer an excellent opportunity to see what works and what doesn’t work.

Mostly, we found that Mr. Obama’s well-meaning words fell on deaf ears. Overall, in fact, his speech provoked intolerance. The president said, “It is the responsibility of all Americans — of every faith — to reject discrimination.” But searches calling Muslims “terrorists,” “bad,” “violent” and “evil” doubled during and shortly after his speech.

Mr. Obama also said, “It is our responsibility to reject religious tests on who we admit into this country.” But negative searches about Syrian refugees rose 60 percent. Searches asking how to help Syrian refugees dropped 35 percent. The president asked us to “not forget that freedom is more powerful than fear.” But searches for “kill Muslims” tripled during his speech.

There was one line, however, that did trigger the type of response Mr. Obama might have wanted. He said, “Muslim Americans are our friends and our neighbors, our co-workers, our sports heroes and yes, they are our men and women in uniform, who are willing to die in defense of our country.”

After this line, for the first time in more than a year, the top Googled noun after “Muslim” was not “terrorists,” “extremists” or “refugees.” It was “athletes,” followed by “soldiers.” And, in fact, “athletes” kept the top spot for a full day afterward.

Jon Favreau, the president’s former chief speechwriter, was not surprised that this line was so effective. He singled it out as the best in an early draft he read, and noticed the many shocked tweets from those who had learned that Shaquille O’Neal is Muslim.

“Finding out that someone who’s been a hero of yours, that you’ve looked up to your whole life, happens to be a Muslim,” Mr. Favreau said. “That’s a pretty powerful reminder, this is a religion that is a part of America and has always been a part of America.”

On the whole, though, the response to the president’s speech shows that appealing to the better angels of an angry mob will most likely just backfire. Subtly provoking their curiosity, giving them new information, and offering them new images of the group that is stoking their rage: That may direct their thoughts in different, more positive directions.

After sifting through the search data, we think there are three things the rest of us not giving speeches in the Oval Office can do.

First, parents should be talking to their kids about how the overwhelming majority of Muslim Americans pose no threat to them.

Second, police departments would be wise to use search data to allocate resources through predictive policing. The data, for example, could tell police chiefs when sending a cop to do an extra drive through a Muslim neighborhood, or making sure that the town mosque was safe overnight, would be a good idea.

Third, Muslim Americans are right to take some precautions. Like most grave threats, hate crimes are rare. Our model suggests that, if Islamophobic sentiment stays at its current level, about one in every 10,000 Muslims will be the victim of a reported hate crime over the next year, similar to the rate of automobile fatalities and orders of magnitude higher than the chance of being a victim of terrorism.

The human capacity for rage and anger will never disappear. But there is a huge difference between this flare-up of hatred and those from decades past. We now have rich, digital data that can help us figure out what causes hate and what may work to contain it. That might offer some hope to Muslim Americans who see a country that right now appears more prone to fury than understanding.

Evan Soltas is a senior at Princeton; Seth Stephens-Davidowitz is an economist and a contributing opinion writer.

Source: NYTimes