By Asanga Abeyagoonasekera 19 July 2023

A report titled Mass Graves and Failed Exhumations in Sri Lanka authored by the Centre for Human Rights Development (CHRD), Families of the Disappeared (FOD), International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP) and Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka (JDS) was released in June 2023[i]. During the report’s release, Human Rights Activist Brito Fernando said, “We are standing on a ground filled with skeletal remains and a country the UN rated second in the world for unsolved enforced disappearances”[ii]. Hundreds of remains were unearthed in some 20 exhumations of mass graves in the past three decades. Former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, ousted by public protest in 2022, was accused of tampering with police records in order to hamper investigations into mass graves[iii]. It is as if Sri Lanka is a case study of the abuse of state power and suppression of human rights throughout its dark history. Presently, the Sri Lankan state is closing its political space through draconian regulations.

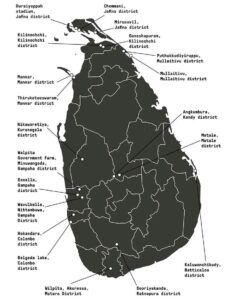

A map of mass gravesites in Sri Lanka from the report.

What is a Panopticon?

The Panopticon was introduced by English Philosopher Jeremy Bentham around 1787. The Panopticon is a large courtyard, with a tower in the centre, surrounded by a series of buildings divided into levels and cells where each cell has two windows: one brings in light, and the other faces the tower where large observatory windows allow for surveillance of the cells. French philosopher Michel Foucault selected Bentham’s Panopticon to examine as a paradigm of a government disciplinary technology. According to Foucault, the cells become “small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible”[iv]. The inmate is not simply visible to the supervisor; he is visible to the supervisor alone– cut off from any contact. The surveillant could as easily be observing a criminal, a schoolboy, a wife, or an individual protestor, such as in the Sri Lankan case. Today, the Panopticon is not a building but a political technology or a ‘surveillance rule’ that suppresses liberty, self-determination, and autonomy.

From Bangladesh to Sri Lanka

The architectural perfection of a ‘panopticon’ is such that even if no guardian is present, the power apparatus still operates effectively. The guardian of Sri Lankan ‘panopticon’ was a project of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the autocrat who the ordinary people of Sri Lanka removed for his illiberal, undemocratic rule, with numerous human rights abuses. With the military at the forefront, unfortunately, this has been carried forward and operated with a fresh outlook, further strengthening the walls of the ‘panopticon’ by the appointed current President Ranil Wickremasinghe.

South Asia has become a victim of many panopticon projects where individuals are disciplined, and institutions are regulated, such as the Electronic Broadcasting Regulatory Commission Act (EBRCA) in Sri Lanka[v] and Bangladesh, the Digital Security Act (DSA)[vi]. Many journalists and activists detained under DSA in Bangladesh have not seen life beyond the walls of the ‘panopticon’; writer Mushtaq Ahmed was one such victim. According to Amnesty International, ‘Bangladesh has at least 433 people imprisoned under the DSA as of July 2021, held on allegations of publishing false and offensive information online’[vii]. (See Table). Sri Lanka is engaged in the same exercise with the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), which will soon follow by another, the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) and EBRCA. According to Dr Harsha DeSilva, the opposition Member of Parliament, “right to free expression is a fundamental tenet of any democratic society. The proposed Broadcasting Authority Act aims to stifle the media, and we will not stand for it”[viii].

Table: Bangladeshis arrested under the DSA by Profession

Autocratic and some illiberal leaders build the modern Panopticon under the guise of national security to discipline the polity. Algorithms and artificial intelligence are used to screen/regulate, and model individual life. Ian Bremmer explained this as a ‘techno-polar world’ order dominated by techno companies making citizens pawns in their digital space[ix].

UNHRC on Prevention of Terrorism Act

The Sri Lankan polity has witnessed several disciplinary projects of the government. These included first the pandemic and its irrational rules, such as forced burial, which impacted the Islamic community. In addition, was the overhyped ‘national security threat’ from extremist groups after the Easter Sunday terror attack and theories about a return of the LTTE (Tamil Tigers) pushed by so-called terrorist experts. The overhyped ‘national security threat’ projected by the State justified the need for more reforms to tighten the draconian Act, the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). The PTA will be replaced by the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA)[x], which many Human Rights activists have already warned against. Sri Lankan authorities cracked down on thousands of protestors under the Wickremasinghe rule using the PTA. As a new leader required more strength to crush future protests, the ATA was designed to provide this. Rita French, the UK Human Rights Ambassador, delivering the statement on behalf of Sri Lanka Core Group comprising Canada, Malawi, Montenegro, North Macedonia, the UK, and the United States at UNHRC, highlighted the grave concerns of abuse of terrorism act, “We remain concerned by the continued use of the Prevention of Terrorism Act.”, and the “government to protect freedoms of expression and association”[xi]. The reason there has not been any progress from the previous regime to the present is the security machinery is handled by the same old guard of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s advisors and officials.

Media Regulations Act

Further, to strengthen the “panopticon”, President is to introduce the new Electronic Broadcasting Regulatory Commission Act (EBRCA). President Wickremesinghe accused the media of an arson attack on his residence, saying, “Why fear about the issuing of (broadcasting) license? Electronic media set fire to my house, in which about 3,000 books were destroyed. It is not just a loss to me, but the country. What are we to do then? Am I to grant licenses for arson? Are you asking for the right to set houses on fire?”[xii]. In the Sri Lankan case, the “supervisor” of the Panopticon is the direct victim of losing his private property due to the absence of people’s discipline followed by the uprising. The supervisor blames the free media and lack of proper regulatory measures for the failure of the disciplinary project as the cause for his property loss and the country’s instability created by protestors.

While justifying the necessity of media regulation, the new Act will be pushed forward.

The Sri Lankan Electronic Broadcasting Regulatory Commission Act[xiii], will establish a separate Broadcasting Regulatory Commission comprising five members. If reports detrimental to national security, national economy, and public order are published by broadcasters, the Broadcasting Regulatory Commission can revoke and temporarily suspend the broadcaster’s license. Further, the Investigating Committee of the Broadcasting Regulatory Commission will have the power to obtain a court order and raid media institutions in the country.

The protestors who are the real victims have a different take, and the protests ended the autocratic rule of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The transition of authoritarian rule to a liberal such as Wickremasinghe ended up as another nightmare where he continued with the same lot of people from the past regime, tightening the rules and surveillance and blaming the protestors as fascists.

Apart from the multiple acts to tighten the regulations and strengthen internal national security, the local elections were continuously delayed blaming the prevailing economic condition. The democratic and political space is closing in Sri Lanka, while the economic space has been opening for reforms.

Towards Economic Stability

There has been progress in economic reforms introduced by Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremasinghe during the last several months. The pragmatic reforms were introduced by IMF and accepted by the President. The IMF has managed to bring some stability to the island nation that was seen as one of the worse economies after default a year ago led to political unrest. The double-digit inflation was similar to that in Zimbabwe, and people were dying waiting at the extended fuel lines and with poverty at 52 percent of the population in estate areas, exacerbating spatial disparities and increasing overall inequality[xiv].

In less than a year, Sri Lanka’s reserves grew by an impressive 26 per cent to touch USD 722 million in May 2023, while the currency rose by 24 per cent this year. The IMF lifeline and other international assistance, such as from neighbouring India, the first country to assist with a direct credit line of USD 4 billion, have helped Sri Lankan economy avoid a Zimbabwean, Venezuelan-styled runaway inflation and return to some stability. Import restrictions of 286 items were lifted from the 1500 items that were restricted last year. Vehicles and many other essential imports remain under restriction. The overall picture depicts the country as slowly but surely emerging from its worst economic crisis. One of the critical ingredients for the modest success was that perhaps economic policy was detached from heavy-handed politics for the first time in its history.

Recently in Japan, President Wickremasinghe apologized for the incorrect policy prescription carried out by his predecessor Gotabaya Rajapaksa, referring to Japan’s LRT project[xv]. Wickremasinghe assured that Japan’s LRT, U.S. investment and Indian projects would move forward during his presidency. He will give the same assurance in Paris to the Paris Club members and in U.K[xvi]. Wickremasinghe was quick to learn the danger of steering too close to China and rejecting the Western projects, a data point captured in my earlier writings from ‘Teardrop Diplomacy’. The political maturity of being six times prime minister earlier has undoubtedly benefited Wickremasinghe, setting him apart from his political contemporaries and winning the West as the most trustworthy political figure committed to liberal reforms.

Opening the economy and closing political space

However, his administration has a grave concern, just like that of his relative J.R Jayawardena, who became the first executive President in 1977 with a two-thirds majority from his political party, the United National Party (UNP). Wickremasinghe has no majority in Parliament and must rely on his predecessor’s political party, the SLPP. Second, Wickremasinghe was not elected by a democratic election; he was appointed by the previous autocratic leader Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Wickremasinghe quickly borrowed the present political reforms from J.R. Jayawardena’s playbook. Jayawardena is the principal reformer who introduced the ‘open economy’ in 1977 to Sri Lanka. His market-oriented liberal open economic policies departing the socialist reforms introduced by Sirimavo Bandaranayake (1971-1977) were praised as a solution to faster development. Sri Lanka was one of the first South Asian countries to liberalize its economy back in the day and align closer to the U.S. during the cold war, despite being non-aligned. There was a darker side to this operation where Jayawardena closed the political space as a pretext for economic development. Prof Jayadeva Uyangoda, a senior political scientist, explains this as ‘Opening the economy and closing the political space’.

Political space was closed in the Jayawardena era, where elections were postponed, and a referendum was used to extend political power. Jayawardena’s autocratic rule interfering with multiple institutions, including the judiciary and free elections, was evident during his tenure. People who revolted against the authoritarian regime were incarcerated. One such person jailed was this author’s father, Ossie Abeyagoonasekera, who opposed holding a referendum to extend the term limit of the autocratic rule in 1982. Many were prisoned during this time as ‘Naxalites’. The democratic space was reduced in the country. The minority communities revolted against the State for abusing their rights. It was a beginning of a three-decade civil war in Sri Lanka.

The closing of the political space on behalf of economic reforms is also visible in today’s context. The closing of political freedom under the guise of the economy or national security will pave the way to include every Sri Lankan in a ‘panopticon’, a disciplinary project which the new leadership thinks is a pre-requisite to carrying out the economic reforms will fail and propel multiple social distresses in the coming months. Sri Lankan president Wickremasinghe must achieve a balance in his political approach than continue with the same autocratic sentiments from the past. Unfortunately, by implementing the EBRCA and ATA, he has chosen a path towards Bangladesh.