Resettling the Unsettled

Practicalities of relocating Rohingyas to Bhasan Char

The Rohingya influx into Bangladesh, described by the United Nations (UN) as the “world’s fastest growing refugee crisis,” has been one of the most discussed humanitarian crises of recent times. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Bangladesh, prior to the latest exodus, had already been hosting more than 300,000 Rohingya refugees.

The latest mega settlement of Kutupalong-Balukhali, with a population of over 600,000 in Ukhia, Cox’s Bazar, was built swiftly within five months. More than 90 percent of the camp population live below the UNHCR emergency standards of 45 square metres per person and at some areas as low as 8 square metres. The overcrowding poses several environmental (e.g. deforestation, contamination), economic (e.g. impact on the host community’s economy, reducing the average wage) and health (e.g. epidemics) risks. Considering the speed and scale of the crisis, the initial response of the host country and humanitarian aid organisations was to provide basic support to the refugees. However, the influx has decreased and the timeline for a safe and Rohingya-approved repatriation back to Myanmar remains unknown. Moreover, the Bangladesh government should rethink how to maintain medium- to long-term support to the Rohingya population in a more structured way while addressing host community needs.

The Bangladesh government had proposed relocating the Rohingyas to the coastal areas in 2015—specifically, to Bhasan Char (originally known as “Thengar Char”) in Noakhali. Recent details of government-approved infrastructure reportedly include 120 plots of land (each containing 12 buildings housing 16 families in a 12-foot by 14-foot unit with shared kitchens and bathrooms), one cyclone shelter and a 2.47m high embankment-flood barrier. At present, talks about Bhasan Char have softened into whispers. There is no telling when the plans may resurface. Thus, a frank discussion exploring risks and vulnerabilities is necessary.

Initially, the relocation idea immediately received scrutiny from the public and organisations such as the UN and Amnesty International. The criticism stems largely because of Bhasan Char’s exposure to natural disasters. This scepticism is anticipated as many are unfamiliar with the char lands.

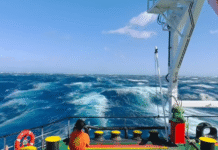

In Bangladesh, close to three million people live on 185 fertile silt islands, known as chars, which are formed by the dynamics of river erosion and accretion. The chars are low-lying areas and the soil is of high salinity. Initially, the forest department develops newly emerged chars for a period of 10 to 15 years. The objectives of the forest department activities are to accelerate accretion, stabilise the land, and protect it against storms and cyclones. Historical trends reveal that during the times when the forest department was in control, poor and landless households located and occupied the chars. According to government regulations and the ministry of land oversight, each household is provided 1 to 1.5 acres of char land.

However, the geographical setting, scarcity of proper infrastructure and isolation from the mainland impede the functioning of administration, and services such as law enforcement, economic participation, health and education are very limited. Adaptability strategies in these areas are strikingly different from the other parts of the country. The chars are considerably more susceptible to covariate shocks due to cyclones, erosion, water-logging, droughts and salinity intrusion. To improve the livelihoods of char-dwellers, several tailored interventions have been designed and implemented. While the beginning of development activities in these areas date back to the late 1970s, the Char Development and Settlement Program (CDSP) maximised the momentum and set itself up as a leading intervention circa 1994. Facilitated by the government of Bangladesh, Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), it has since expanded into several phases. This programme offers a wide range of support components that target livelihood in the chars among other areas. A recent CDSP study revealed that successful livestock rearing training positively influenced food consumption and increased entrepreneurship as well. In addition, there was an improvement in water and sanitation practices along with an overall increase in human rights awareness.

Undoubtedly, the CDSP programme has elevated living standards in the chars that improve at each programme phase although it is unclear whether the programme would be implemented in Bhasan Char. Habitation of Bhasan Char is widely debated, yet key questions surrounding security, economic participation and language are left unanswered. In addition, there is the question of the availability of health and education services.

The lack of law enforcement is a concern. Before 1994, char laws stated that the government automatically owned char lands. However, recent amendments suggest that government ownership applies if no private claimant establishes prior ownership rights. In addition, the lack of day-to-day char governance has created scope for manipulation among the char population. Mirroring a feudal system, jotedars—a class of “rich” peasants living on the mainland coast regions—have their own puppets called lathyals to control char dwellers. Ironically, the lathyals, using violence and intimidation, promise char dwellers security over other extraneous threats at a cost, collected as a form of rent. Their sinister antics also target government officials. Blurred property rights and the absence of government control create security risks for the Rohingya population. Not to mention, approximately 80 percent of the Rohingya population are women and children.

Typically, char dwellers work on economic activities such as livestock rearing, farming sustainable vegetation and fishing. These activities wholly depend on mainland trade. The government will potentially allow the Rohingyas to work on Bhasan Char but they have not revealed the specifics yet. Will the government allow the Rohingya population full access to mainland markets? If yes, how will Rohingyas travel to the mainland? The inter-char transport system is active albeit limited to water-based methods. Beyond economics, water transport is necessary during frequent seasonal threats. Does the government plan on granting Rohingyas the freedom to move in and out of the char?

Another source of concern that has not been addressed is the language barrier. The dialect the Rohingyas speak is fairly close to Chittagonian, which is the local dialect of Chattogram and Cox’s Bazar. This fluidity in communication promotes stronger integration and opportunities. However, this advantage dissipates should they move to Bhasan Char where the local dialect (Noakhali) is quite different.

Char health services have improved thanks to organisations such as BRAC, but are not near mainland capabilities. Some trained medical workers provide on-site medical care such as women’s health services. However, char dwellers depend on untrained practitioners.

Approximately 60 percent of the Rohingya children population require education, though NGOs can only provide foundational learning. Provisions for higher education are non-existent. How does the government propose to educate the Rohingya youth at Bhasan Char? It should be noted that seasonal extremes affect their school attendance too.

Discussion with aid personnel on the ground revealed that many Rohingyas harbour the desire to return home if their citizenship rights are restored. Relocating to Bhasan Char will, in effect, leave them one step removed from this possibility ever occurring. In the medium- to long-term, they believe in integration possibilities and enjoy a sense of familiarity with the Cox’s Bazar terrain. Recommendations have been offered to ease host community tensions. For instance, the government and NGOs can do more to address major host community needs; joint programming on projects such as the World Bank’s proposal to tackle deforestation serves as a strong community-building opportunity. In fact, recent survey results indicate that 58 percent of Rohingyas, who want to meet with host communities, believe not enough is being done to do so. Likewise, half the locals who want to meet with the Rohingyas agree.

Indeed, Bangladesh has generously sheltered the Rohingya population amid the mass exodus. Now tasked with considering medium- to long-term solutions, the international community must step up to assist Bangladesh with fair and adaptable options. Security, economic participation, communication, health and education are key elements involved in achieving solutions. Moreover, listening to stakeholders such as host communities and the Rohingya population should remain a top priority.

Farzana Misha is a development researcher at ISS, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Dimple T Shah is an attorney in the United States as well as a human rights and immigration activist.