Repatriation bids: Designed to fail, all along

Myanmar, which is accused of genocide against the Rohingya population, has done little to create conditions that encourage the refugees to return from Bangladesh and to hold the perpetrators of the alleged genocide accountable, analysts say.

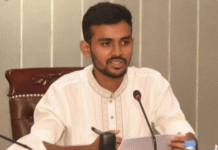

Dr Mizanur Rahman, a law professor at Dhaka University, said that while bringing the perpetrators to justice was important, ensuring the repatriation of the refugees was more crucial for Bangladesh.

Bangladesh now hosts some 1.1 million Rohingyas, including the 743,000, who fled the brutal military crackdown in Rakhine since August 25, 2017.

Before they go back to their homeland, the Rohingya wants guarantee of citizenship, safety in Rakhine state from where they were forced to flee, freedom of movement, recognition of their ethnicity and returning to their original homes, not to the camps.

But Myanmar has made no such commitments. As a result, both the repatriation attempts — one on November 15 last year and the latest on August 22 — fell flat.

Bangladesh has not been able to draw the expected support from China, India, Japan as well as the ASEAN either, resulting in the delay in repatriation, legal and international relations experts say.

For its part, Bangladesh, influenced by China and India, has been lenient in its approach, they add.

The 1982 CITIZENSHIP LAW

Myanmar does not recognise Rohingyas as its citizen since 1982.

A major recommendation of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine, which was formed in 2016 to make concrete suggestions for development and peace in the conflict-prone state, was amending the citizenship law of 1982, aligning it with international standards to make it equal for all regardless of religion and ethnicity.

“A single act of amending the law and granting citizenship to the Rohingyas could be the most fundamental change that would draw the Rohingyas back to Myanmar,” said Prof Imtiaz Ahmed of the International Relations Department at Dhaka University.

However, there has been no move to this end so far. This means Myanmar is not sincere at all about the repatriation. “It is rather playing diplomacy with Bangladesh,” he said.

Myanmar has set conditions that the ethnic minority group has to accept the National Verification Card (NVC), which it claims is a pathway to citizenship. Rohingyas, however, refuse to accept it.

The provision of NVC was also incorporated in the repatriation deal signed between Bangladesh and Myanmar in November 2017.

Before the latest repatriation move failed as no one volunteered to return, leaflets issued by the Myanmar government were circulated among the refugees in Cox’s Bazar, saying they have to accept NVCs after repatriation.

“Why should we accept NVCs? It’s meant for foreigners. We were born in Myanmar and our forefathers lived there,” said Razia Sultana, a Rohingya lawyer working for the refugees’ rights.

Myanmar also does not recognise the Rohingya ethnicity, another core demand of the Rohingya. “It’s the question of our identity, but that’s denied by Myanmar,” she said.

SAFETY IN RAKHINE

Safety remains a major concern for the Rohingyas, who saw their relatives killed and raped and their houses burnt to ashes by the Myanmar military.

“Now the presence of army is even stronger in Rakhine State,” said Razia.

An international research last year found an estimated 25,000 Rohingyas were murdered and 19,000 Rohingya women and adolescents raped during the military crackdown in Rakhine since late August 2017.

The research, conducted by a consortium of academics, practitioners and organisations from Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Norway and the Philippines, also found around 43,000 Rohingyas suffered bullet wounds, 36,000 were thrown into fire and 116,000 beaten up by the Myanmar authorities.

Independent UN investigators found the crimes by Myanmar military had genocidal intent and demanded investigations against them.

However, the UN Security Council could not take any concrete action against Myanmar because of opposition from China and Russia, two veto powers, over the last two years.

Myanmar denies the allegations, saying the military action was in response to attacks on police camps by Rohingyas.

Even two years after such brutality, the UN, independent journalists and many aid agencies do not have access to large parts of Rakhine. In many places, internet connections were snapped amid clashes between Arakan Army and Myanmar military, Razia said.

“Rohingyas don’t feel safe at all to return there under such circumstances. Should we go to the dark places?”

Joseph Tripura, spokesperson for UNHCR in Dhaka, said the UN refugee agency does not have access to many parts of Rakhine, which prevents the agency from fully assessing the conditions of return.

The agency does not believe the current situation is ready for a large-scale repatriation, he added.

Razia said Rohingyas demand international peacekeeping force, especially the ASEAN force, to ensure their safety when they return. But until now, there has been no such move by Myanmar.

‘WANT TO RETURN TO OUR HOMES’

About 128,000 Rohingyas, displaced during the communal clashes between 2012 and 2016, were kept in the IDP (internally displaced people) camps in Myanmar. Some of those who moved out were put in newly built camps where they face restrictions of movement and other human rights violations.

A network of official checkpoints and threats of violence by local Buddhists prevent Muslims from moving freely in Rakhine. As a result, they are cut off from sources of livelihoods and most services, and reliant on humanitarian handouts, according to a Reuters report.

“We know that thousands of Rohingyas back in Myanmar are still in those camps facing difficulties,” said a Rohingya leader from Camp 25 in Shalban of Teknaf.

“The Myanmar government says they have built camps for us. We don’t want to return to camps. They are no better than confinement. We want to return to our homes,” he said.

Besides, if Myanmar was really sincere about taking the Rohingya population back, it would take back some 6,000 Rohingyas, who have been living in no-man’s land near Ghundhum of Naikhyangchhari since late August 2017, said Syed Ullah, a Rohingya from Kutupalong in Ukhia.

ROHINGYAS NOT ENGAGED IN TALKS

The Rohingyas also feel ignored as they were not included in the talks about the repatriation, their leaders say.

Bangladesh signed a repatriation deal with Myanmar in November 2017, while the UNDP and UNHCR signed a tripartite deal with Myanmar in June last year. Since then, these parties held numerous meetings and made decisions about their return.

“However, there was no representation of the Rohingyas in these meetings,” said Mohibullah, chairman of Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights (ARSPH), a Rohingya organisation based in Kutupalong camp.

In June last year, the ARSPH also wrote to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, requesting her to make them a party to the discussion.

“If we can talk directly, we can raise our issues the way we see with the Myanmar government,” Mohibullah told The Daily Star, adding that it can reduce the mistrust and misperceptions.

On Thursday, Bangladesh Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen also underscored the issue of distrust, a big factor why they fear to go back to Rakhine.

“I think Myanmar should take some Rohingya leaders to Rakhine to show how they have improved the situation over there,” he told reporters.

BANGLADESH’S STRATEGIC MISTAKE

Prof Mizanur said Bangladesh made a strategic mistake by signing the bilateral deal with Myanmar.

Since it was a decades-long crisis and Myanmar was mostly responsible for it, Bangladesh should not have signed the bilateral deal hastily. It should rather have given the responsibility to the international community, he said.

“The momentum of international pressure that was there in the beginning has died down because of the bilateral nature of the deal,” he told The Daily Star on August 23, a day after the second repatriation attempt failed.

Those who supported the bilateral deal, including China and India, are not being able to create pressure on Myanmar for fundamental changes required for the repatriation, Prof Mizan said.

“What is most important now is the role of the international community, including the UN. They should continuously monitor the situation in Myanmar and press for the changes required for repatriation,” he noted.