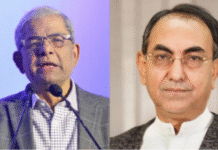

Recalling BRAC’s journey

How Brac became what it is

There are not many non-Bangladeshis who witnessed both the birth of the Bangladesh nation in 1971 and the beginning of BRAC in 1972, and I hope that those reading these few words will find my memories of some interest.

Over the months prior to Victory Day in December 1971, when I was coordinating the large Oxfam Bangladesh Refugee Relief Program in India, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, known to me as Abed Bhai, was shuttling between London and Calcutta, raising awareness in the UK and delivering relief supplies in the refugee camps. During this time, Oxfam in Oxford became aware of the dedicated energy of Abed Bhai.

In January 1972, Abed came back to Bangladesh and it is on record that he went to Sulla in Sylhet on January 17 which is where BRAC’s first work began.

It is a coincidence that I travelled overland from Calcutta to Dacca at the same time and was involved in the initial assessment of what Oxfam might be able to do in Bangladesh. After I returned to Calcutta and was involved in the careful closing of Oxfam’s refugee program, I received instructions from Oxfam to handover Rs300,000 to Abed and this I did in early February 1972.

Oxfam already knew that Abed was preparing a rehabilitation program and this was, in a way, an advance payment. Oxfam’s first field director for Bangladesh, Raymond Cournoyer, had initially angered Oxfam HQ by saying that he did not want to be involved with the distribution of relief supplies in Bangladesh.

Raymond, a Catholic Brother, who had worked in erstwhile East Pakistan from 1958 to 1965, told Oxfam to give relief supplies to Mother Teresa and CARITAS but that he wanted Oxfam funds to support “young Bangladeshis with vision.”

The first grant from Oxfam for both rehabilitation and community development, from Oxfam-UK and Oxfam-Canada, totalled 132,174 British pounds and was for seed, fertilizer, boats, fishing equipment, tools, drugs, salaries, vehicles, and 6,000 houses.

This was approved by Oxfam in March 1972 but the 300,000 Indian rupees had already been spent earlier. When Abed came to Calcutta in February 1972, the initial shopping list that I still have read:

Carpenter’s tools

50 nine-inch planes

30 measuring tapes

30 files

30 pliers

60 saws

Weaving equipment

80 handlooms

Harvesting tools

1,000 sickles

1,000 scythes

Implements for works program

3,000 kodal

3,000 baskets

House-building program

1,000 hammers

100 one-inch and half-inch chisels

1,000 ram daos (axes)

1,000 eight-inch screwdrivers

1,000 shovels

Abed also went toAssam and procured three million bamboos which were floated down the rivers to Sulla. Providing tools such as these was to enable some families to earn a living again as well as providing the means to rebuild village homes. Most household tools had been burnt or stolen.

In Oxfam’s project approval document, the following has been written regarding the housing needs which shows how carefully and thoughtfully Abed had thought everything through:

“Housing: Although the project area was fortunate in that few permanent buildings were damaged, a number of villages were completely destroyed and there is an urgent need to replace 8,600 houses before the monsoons. Traditional house-building materials are bamboos for walls and corner-posts and grass for roofing.

“These provide the barest protection for survival and are quite useless against floods, cyclones, and tidal bores, but BRAC has set its face against an ambitious program for improved housing, believing that this can follow when the economy is revived and developed.

“However, they are taking the opportunity to redesign the layout of 10 villages with an eye to future development needs and public health. A team of architect/surveyors are now looking at this question and, meanwhile, BRAC volunteers are discussing the ideas with the traditionally conservative villagers to ensure their acceptance.”

Later on, further Oxfam grants covered other areas of development work such as public health, family planning, functional literacy, and working with women. Since the late 1970s, I have either been living and working in Bangladesh or visiting and have hardly missed a year since then. It has been most interesting to watch BRAC grow.

When I was visiting the field-work of BRAC in the 1980s, Abed would always ask me: “What did you see? What do you think can be done better?”

He was always seeking constructive criticism and indeed BRAC’s own Research & Evaluation Division has been key to maintaining BRAC’s high standards as well as learning valuable lessons when something has actually failed.

On one occasion I said that I did not see very many women field workers and on another occasion, I asked if more could not be done to see if children with disabilities could be helped to come to the BRAC schools. Every time action was taken to change things for the better.

It will be fascinating and educational to follow BRAC’s future journey as a new generation takes over the leadership and faces new and changing challenges.

Julian Francis has been associated with relief and development activities of Bangladesh since the War of Liberation. In 2012, the government of Bangladesh awarded him the Friends of Liberation War Honour in recognition of his work among the refugees in India in 1971, and in 2018 honoured him with full Bangladesh citizenship.