Paddy Procurement System: Farmers lose out due to moisture

The required level of moisture content set by the authorities has become another big headache for Boro growers hit by falling prices, as it makes most of them ineligible to sell their produce to the government.

Under its ongoing procurement programme, the government is buying 1.5 lakh tonnes of paddy from farmers across the country. One of the prerequisites for selling paddy is the moisture content must not exceed the maximum recommended level of 14 percent.

Visiting different upazilas in Rajshahi, Naogaon and Bogura, The Daily Star correspondents found that most of the marginal farm-ers could not sell their paddy to the government buying centres, known as local supply depots. Even if they had the opportunity, high moisture levels of the paddy dashed their hopes.

In addition to imposing limits on moisture, the government’s Food Procurement Policy 2017 set some other requirements — the produce must not contain any external materials above 0.5 percent, any other rice variety above eight percent, immature grain more than two percent, and sterile rice beyond 0.5 percent.

Though the primary goal of the procurement policy is to “give en-couraging price to the farmers” and keep the rice price stable in the open market, the reality was different.

The marginal farmers hardly get the benefit of the procurement policy because, food officials say, they can meet other criteria but not the moisture limit.

When farmers harvest paddy, the grains have a moisture level of 18 percent. After that, even if they dry the paddy on the clay yard several times, the moisture level would not come down to below 16 percent, said a food ministry official.

“It is not possible to reduce the moisture level down to 14 percent without drying it on the concrete surface. So, most of the margin-al farmers get rejected when they take their produce to the local supply depot. Taking advantage of the situation, rice mill owners and traders are selling paddy to the government,” said a food directorate official.

Asked why there has to be a moisture limit, the official said if the moisture level crosses 14 percent, the grains will dry up after storage and its weight will drop.

“The paddy weight will fall by at least 1kg per maund (40kg) af-ter one month. Then the official in charge of the local supply depot will be in trouble,” he said, seeking anonymity.

The farmers in West Bengal, India face a similar problem, but still their government buys paddy with higher moisture levels and dries it after storing, he said.

“If we want to help our farmers, we need to have a similar system by changing the procurement policy.”

Many of the farmers in the three districts reported that they were denied sales because of low dryness levels.

Abul Kashem, a farmer of Mohonpur in Rajshahi, has his agriculture card and a surplus of paddy but he could not sell it to the open market because the price was below the production cost. And then he was rejected at the government depot.

Asked for the reason, he said whenever he went to the depot, the officials said the paddy was not dry enough. “They do not buy from us,” Kashem said.

During a visit to his home, piles of paddy were seen kept on the veranda.

Another farmer, Mainul Mia of Mahadevpur, Naogaon, expressed helplessness because he could neither sell his paddy at the gov-ernment procurement centre nor in the open market.

Food officials said they had nothing to do but follow the procure-ment policy.

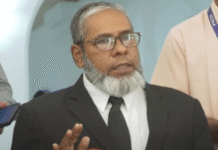

Md Kudrot-E-Azom Sumon, assistant sub-inspector (food) at local supply depot of Bogura Sadar upazila, said, “Since the food minis-ter opened the procurement activity on May 15, they have been able to buy only 24 tonnes until May 29, and rejected around 50 listed farmers as their paddy had dryness below the required level.”

In the meantime, the middlemen are capitalising on farmers’ plight by collecting paddy from them, getting the grains dried on a concrete surface, and eventually selling it to the government depot using the names of the listed farmers.

At the sadar upazila depot, our Bogura correspondent met a broker who claimed himself to be a listed farmer and came with three samples of paddy.

When asked his full name and address in front of the officer in charge of depot, Ashraful Arifin, the broker used the name of a farmer of Chandpur village in the sadar upazila.

But in the face of repeated questioning about other information, he gave his true identity — Anamul Hossain, 38, of Khidradhama village in the sadar upazila — and the details did not match with the list.

Anamul admitted that he was not a farmer, and he came with the paddy samples of his neighbours. He bought rice from farmers in his area and had it dried at a drying facility, and tried to make sales using their agriculture cards.