Mujib’s failure with BaKSAL: Lessons for Sheikh Hasina

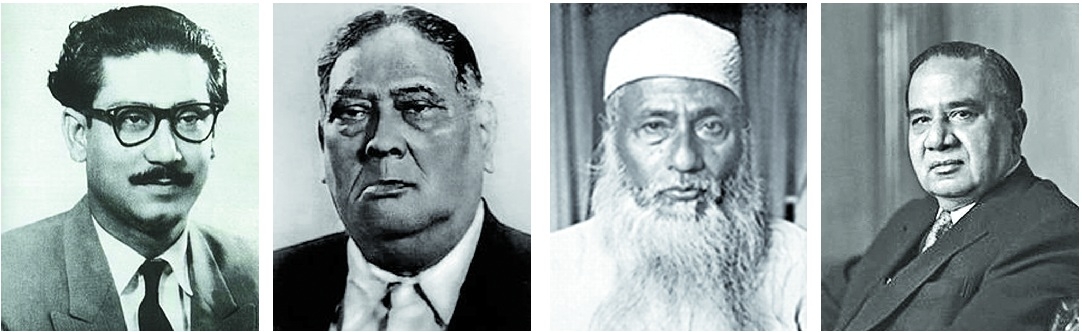

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Abul Kashem Fazlul Huq, Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Abul Kashem Fazlul Huq, Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

by N N Tarun Chakravorty 22 September 2019

One veteran leftist politician who lived in close proximity with Sheikh Mujib in jail for a long time, in a private conversation with me, said, ‘Suhrawardy was his brain and Maulana Bhasani was his heart.’ This observation seems to reveal the truth when we learn that Sheikh Mujib met Suhrawardy when the latter, as a minister, went to visit a school in Gopalganj, where Mujib was a student. It is Mujib who led the students in pressing their demands for the development of the school. Suhrawardy found ‘something’ in the boy and gave him his telephone number and address, and asked him to meet him if he is in Kolkata. Smart (and far-sighted?) Sheikh Mujib preserved the number and address with great care and one day he really arrived in Kolkata and met Mr. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and took the first lesson of politics. Mujib maintained this guru-disciple relationship all through life at least apparently.

When the veteran leftist politician says, ‘Suhrawardy was his brain’, we need to understand Suhrawardy; otherwise, we cannot understand Sheikh Mujib’s brain. It is difficult to make a blanket comment on Suhrawardy because scholars do not reach a consensus in defining him— in determining his role in certain historical events, for example, in the Kolkata riot of 16 August 1946, in detecting his intention about certain issues, for example, how sincere he was in fulfilling the interest of the Bengalis as against the West Pakistanis (he showed little interest in upholding the interest of the then East Pakistan, which angered his own party leaders of Awami League, namely Maulana Bhasani, who nominated him as the Prime Minister forming United Front), and his belief in democracy let alone secularism. Here we need to have a clear understanding of democracy and secularism. Suhrawardy’s involvement in Muslim League makes him unqualified as a secularist no matter how logical it might be for the Muslims to desire for a state separated from the Hindus’. Any humanist would stand for upholding the backward Muslim community in the then India, but for doing that, he or she would not do religion-based politics or belong to religion-based organizations. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and M K Gandhi are two burning examples in this regard. It should also be clear that one cannot claim to have belief in democracy while he is not a secularist (a theoretical explanation is beyond the scope of this journal). However, how we can describe Suhrawardy without caveats is that he was a bourgeois gentleman having a fascination for Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, who was a lover of American-style capitalism and supporter of US foreign policy. We know, he was connected with many labour unions but did he really belong to the workers? One anecdote shared by one of the leaders of the labour union of the Inland General Navigation & Railway Steam Navigation (IGN&RSN) provides answer to this query: he became the lawyer for the owners of the IGN&RSN, who sued the workers for going on strike on Khidirpur dockyard and creating disturbances. When workers said to him, ‘Sir, you are our leader and you have undertaken to plead for the owners who do not offer us what we deserve and has filed a case against us!’ Suhrawardy replied, ‘Well, you know, I am a lawyer by profession; I will, therefore, work for anyone who pays me. If you paid me, I would plead for you.’

The observations and anecdotes presented above give us some idea about Sheikh Mujib’s ‘brain’ as his mindset was formed in Suhrawardy’s way. Coming in close touch with such a prominent leader in an early stage of life, who brought him into politics, quite naturally constructs the making of his political life in that ‘prominent’ way. What it is supposed to mean is that capitalist democracy was ingrained in Mujib’s mindset as a politician and he never believed in socialism or dreamt of Bangladesh as a socialist state. If he did, he would introduce socialism at the beginning of the newly born country. He rather refused to run the state following socialist ideology as proposed by the socialist faction of the youths and students led by Serajul Alam Khan, the founder of Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal. In the end, Mujib clearly said to Mr Khan, ‘Seraj, I cannot be a communist’.

However, Mujib excels his guru at least in two dimensions: in upholding the interest and in preserving the identity of the Bengali. In the Constituent Assembly in 1955 young Mujib protested the naming of ‘East Pakistan’ and pleaded for ‘East Bengal’ with explanations. He protested the ban on the broadcast of Tagore song and roared his ‘order’ to start broadcasting Tagore song within 24 hours. These incidents give testament to his stand for Bengali nationalism and culture. His love and sympathy for the poor and the subaltern, has been expressed not only in many incidents of his early life and then in his speeches before and after the independence of Bangladesh but also in his lifestyle and behaviour with them. His close observation of Bhasani’s life brought his natural love for the people into politics in the form of his efforts to build a state which would ensure the economic emancipation of the subaltern people.

The discussion above has now set the dais to proclaim the genuineness of Mujib’s pro-poor politics. But the point is, he never accepted the socialist philosophy which was believed by millions of people all over the world in his time as a mantra for the emancipation of the have-nots. To make it further clear, he was not a socialist in the sense it should mean as a terminology of communist literature. To be a socialist one has to take socialism as the philosophy of life and then live as a socialist in personal and political spheres. He must form a political party taking the philosophy of socialism and, each and every member of the party must live the life of a socialist, live a collective life with party members with the same interest and practice equality in every sphere of life over years— maybe over the whole life.

Then, why did Sheikh Mujib who is not a socialist, introduce Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BaKSAL), a one-party rule? Was the true aim to build a socialist state? If we look at some observations made by scholars, we may have some sense. British author, David Urch in his book ‘Crescent and Delta: The Bangladesh Story’, observes that Sheikh Mujib, the president was frightened by the growing opposition and protest from political parties like Jatyia Samajtantrik Dal and discontent of the people. In fact, he wanted to suppress political activism against his government and buy time with dramatic gestures. David Liews, professor at London School of Economics, in his book ‘Bangladesh: Politics, economy and civil society’, writes: the fact that the government headed by the father of the nation in the beginning of the independent state from 1972 to 1975 became extremely authoritarian by nature to tackle the activities like hijacking, looting, hoarding, smuggling, robbery, black marketeering, killing both by the ruling party people and the opposition, and the rebellion posed by some newly formed radical left-leaning parties…’. Mushtaq H. Khan, a Bangladeshi political economist, professor at SOAS, London, explains the situation in a similar fashion: the central leadership failed to control rent-seeking and then lost control over all rents because the nationalist leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s rent control strategy was still centrally controlled in the form of a one-party socialist state, which, was socialist merely by name. Professor Khan in that article, describes the regime from 1971 to 1975 as a ‘period of intensely unproductive “primitive accumulation” and a failed attempt to institutionalize a one-party populist authoritarianism’ (Khan 2013, p. 5).

This situation needs some explanations with theoretical insights: To prevent the people belonging to the government and the ruling party from being corrupt, some kind of checks and balances is a must. In a capitalist democracy these checks and balances are the opposition parties inside and outside the parliament, free media, independent judiciary, independent anti-corruption commission, independent election commission, civil society, humanitarian organizations and so on while in a socialist system these checks and balances are created within the party. Let’s look at how checks and balances are ensured in a one-party socialist system. Canadian citizen and professor of International Development Studies, Isaac Saney provides an account on Cuban system in this regard, which in brief is like this: The 1991 congress was preceded by discussions involving 3.5 million Cubans more than a million people in 89,000 meetings directly raised more than 500 issues and concerns, ranging from the structure of the party to foreign policy. The Cuban electorate is divided into 14,946 circumscriptions, each consisting of a few hundred people. In street meetings that typically see a high degree of participation, each circumscription elects a representative. These delegates, along with representatives of a variety of “mass organizations”— civil groups, student associations, and unions— form commissions which spend over a year selecting from thousands of candidates to ensure that all of Cuban society is represented in the provincial and national assemblies. The Communist party is prohibited from participating in the selection process. These recommendations are then submitted to municipal assemblies for approval. Each Cuban citizen is presented with a list of 601 candidates which they can vote either for or against. To be a representative in the national assembly: each candidate must receive at least 50 per cent of the vote in her constituency. Fidel Castro described this movement as the “parliamentarization of society” which sidesteps the divisiveness of the “dominant model” of western governance, creating “a democracy that really unites people and gives viability to what is most important and essential, which is public participation in fundamental issues.” The author observes: “those who have the most money do not have political power, as they have no support among the masses and, thus, do not offer up candidates in the elections.”

The BaKSAL system had none of the two patterns of checks and balances described above. Therefore, the people working in the government, politicians, ruling party members, in absence of checks and balances, quite scientifically became corrupt and tyrannical. The take-away lessons from the failure of Sheikh Mujib are: Such a political move (introduction of a socialist system) requires theoretical knowledge (how to launch a socialist system has been explained above briefly) but Mujib did not have that. Being a good person and making sincere efforts to improve people’s life is not enough to be a successful ruler. Secondly, throwing moral advice or threatening the wrong-doers does not work. What is needed is a scientific system or mechanism which automatically prevents people from being immoral.

At present, in the regime led by Sheikh Hasina there are no patterns of checks and balances because the opposition in the parliament is a makeshift opposition which does not serve as checks and balances at all. If Hasina truly wants to develop the nation, her foremost task would be to cure the ruling party, government and bureaucracy from corruption, and she cannot eradicate corruption without checks and balances (scientifically impossible). If she doesn’t, she will fail like her father. She has a number of options: 1) to allow BNP to do politics and hold fair elections; 2) to help the formation of an alliance consisting of progressive/leftist parties in the way Jawaharlal Nehru did when he had realised that there were no sizeable opposition in the parliament and that without opposition parliamentary democracy does not work, and by doing this, she can replace BNP by a progressive force in the long run; 3) she can give full autonomy to the anti-corruption commission, judiciary, election commission, police, media, allowing free speech, which would act as checks and balances for the government and the ruling party. It is high time for her to do that because if the situation worsens further, it would not even be possible to execute these measures.