Kayes Ahmed

I am on one of my periodic swings thru Bangladesh and other Asian countries from which we source products for our little garment design and wholesale business based out of Colorado, USA. Since I am a Bangladeshi by birth it has been a natural quest for me to try to do as much business as I can do profitably in Bangladesh. So after years of effort, what have I to show? Shunyo, zero, zip, nada! I have singularly failed to participate in the burgeoning garment export sector of Bangladesh.

What am I doing wrong? Probably everything and nothing. As I was pondering this I got an email from a bdnews24 sub-editor with a complicated name who says, “Kayes Bhai, Some of my friends are textile engineers. I always get fascinating insight about the garments sector from them. For one, I learned that female garment workers have a much more liberal lifestyle than middle class or upper class women in Bangladesh, a fact that still astonishes me from time to time. One friend, a merchandiser, told me the industry loses A grade work to India all the time. Apparently only a handful of companies can handle quality work. The workers just aren’t skilled enough, he said”

I think I will take the liberty to talk about “female garment workers have much more liberal lifestyle” some other time. Actually another friend thinks the garment industry has made the whole country far more promiscuous. I say Amen to that, but that is for some other rant. Let us address the issue of “loses grade A work” to India. I do not know how my sub-editor friend defines grade A, but we at Icelandic Design sell a few million dollars’ worth of garment each year which retail for between $200 and $450. Compare this to retail of $14 to $49 for the mass merchandiser. We are what is known in the industry as a Bridge brand.

Without boring you all to death it simply means that we play in an entirely different marketplace than say, Wal-Mart, K-Mart, Sears, H&M, Primark and so on. We sell small quantities but high price and our competitive advantage is not in price but style, quality and the actual comfort of wearing our clothes. We are at the top end of the value ladder in our industry. But, we cannot seem to produce in Bangladesh! Keno, why, por que?

It is my conclusion that it’s not the workers and their skills but it is that Bangladeshi garment owners who are simply not ready quite yet to move up the value ladder. What does that mean, you ask?

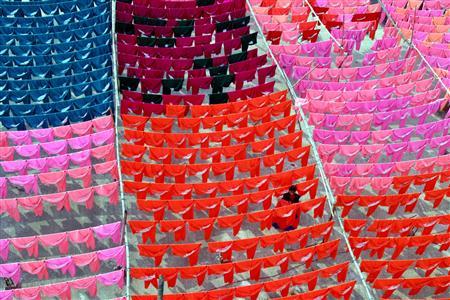

Let me try to explain. So, Bangladeshi garment industry has a single competitive advantage, it is its low labour costs. Everything else can be substituted at parity with China, Vietnam, India, you name it. The low labour costs can only translate into profits if there is high volume and the products are totally standardised. In essence the Bangladeshi industry is substituting human beings for machines because these humans cost less than the machines to run, specifically something like $64 or Taka 5,000 per month.

A decent shirt costs about $120 to buy in the US unless you are buying at Wal-Mart. So, the factory owners fight for every penny, and every large order and every customer regardless of their provenance and their market reputation. The industry is always tottering on the verge of some perceived catastrophe that can take away the orders.

Yes, it is a genuine and a real fear. I am surprised that impact of Rana Plaza and other disasters was somewhat minimal on the order rate and the financial viability of the business. But, the fear underlies something more dark. The garment sector in Bangladesh has very little control of its destiny. They live by the sword of low wages and they may die by the same sword.

The problem is that the buyers that buy at the low end of the spectrum are conditioned to look for the marginal benefits that are measured in pennies. Everything being equal they would rather buy their goods in China where the infrastructure is better, beer is easily available and the business community is much more tuned to the ways of Western businesses. But, everything is not equal, the average wage in China is about $600 compared to the $65 in Bangladesh. So, Bangladesh is stuck in the low end of the scale and that probably is good thing. This is just a phase of the development of the industry.

What about my editor’s lament about losing “A grade” work? That will go on until there are new sets of entrepreneurs in Bangladesh who want to move up the value ladder. These folks would have to be happy with building long term relationships and investing in relationship equity.

Those are big words, what do they really mean? At the very rudimentary level it means that the factory owners must learn to say no to huge volume and low margin businesses, not easy to do if you are under constant cash pressure. It is better to make $2 profit on a $15 item than $0.20 on a $2 item. You need to sell 20,000 items to make $4,000 profit if you are making $0.20 profit per item. Whereas, you can make the same $4,000 if you make 2,000 items but make $2 per item profit. This requires a steady belief that the supply chain relationship all the way to the end consumer is built on quality, value and other intangibles that the big outfits simply do not have. The big mass retailers have cadres of 22-year-olds straight out of college doing 2 year stints as Assistant Buyer or some such fancy title. Their main qualification is that they have read a book or two and they can order complex skinny Starbucks coffee with all sorts of stuff in it.

Equity relationships basically require that the Principals work together to build relationship based on performance which eventually builds trust. That is a long term thing and as my Chinese friend Thomas says, Bangladeshi factory owners cannot see 2 centimeters beyond their noses and immediate profits.

So, developmentally speaking Bangladesh is not ready to move up the value ladder. However, I see some glimmer of hopes. I have met a few young people under 30 who are beginning to settle on relationship equity model. Their problem is that capital is scarce and expensive. In the Silicon Valley if you have a good idea, failed couple of times actually working and can talk then you are likely to get funded for your idea. No, such avenues exist in Bangladesh.

The investment requirements are huge is relative terms to get a bonded license and other bureaucratic silliness. The large factories work like a guild in some way and restrict entry. That would be fine if they could move towards an equity relationship model but their structure and cash burn prevents them from doing that. So, I think we are stuck in the low end purgatory for a while until a critical mass of guys like Rasel (a 30 year old I met recently) can actually move in the equity relationship space by sheer dint of their willpower. I wish them luck and maybe a little support.

Source: bdnews24