Habib Khalasi, a migrant worker from Faridpur’s Bhanga upazila, went to Saudi Arabia in 2019 to turn the wheel of fortune for his poor family. But he returned home in a coffin last year.

The 33-year-old father of one was a metal-scrap worker in Riyadh until his life was cut short by a large metal piece that fell on his head while working at an old camel shed in a desert outside the Kingdom’s capital on May 3.

“When he left for Saudi Arabia, our family was facing hardship. As he started sending money home, we thought our hardship was over,” his younger brother Mahbub Khalasi, an undergraduate student, told The Daily Star over phone.

With Habib now dead, his elderly parents and minor son have been staring at an uncertain future.

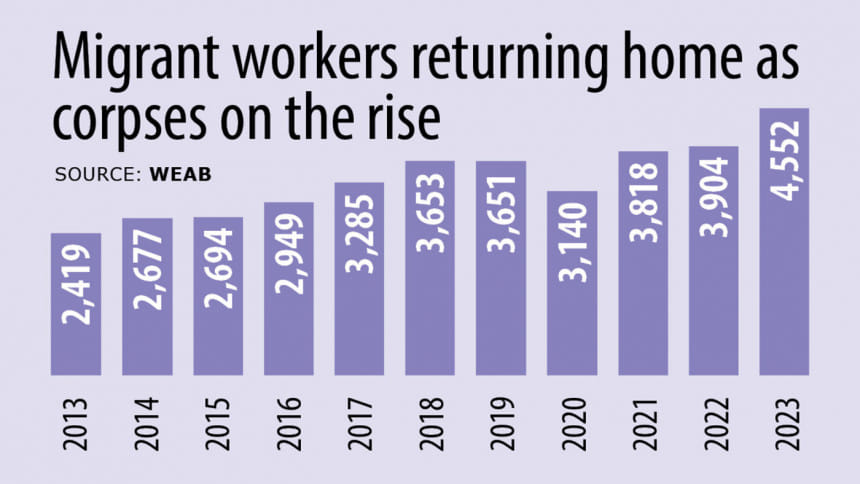

Habib was one of the record 4,552 ill-fated migrant workers who returned home as corpses last year, shows Wage Earners’ Welfare Board (WEWB) statistics. A year before, 3,904 migrants returned as corpses.

Every year, a large number of migrant workers go abroad with dreams but many of them return home in coffins after facing dire situations in the Gulf region, the main destination for Bangladeshi migrant workers, and various other parts of the globe.

The WEWB published data of as early as 1993. Since then, Bangladesh received 51,956 corpses of migrant workers and 34,323 of those arrived in the last 10 years.

A multi-country study suggests alongside poor occupational health and safety practices, low-paid migrant workers in the Gulf region are exposed to a series of cumulative risks to their health, including heat and humidity, air pollution, abusive working conditions, psychosocial stress, hypertension and chronic kidney disease.

However, the deaths of migrants in the Gulf region in many cases remain “effectively unexplained” even though corpses continue to pile up, according to the report “The Deaths of Migrants in the Gulf”, published in 2022 by the Vital Signs Partnership (VSP), a collaboration of migrant rights groups of labour-sending countries of south and southeast Asia, including Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU) of Bangladesh.

Between July 2017 and June 2022, Bangladesh received 17,871 dead bodies, 67.4 percent of which arrived from the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain, according to WEWB annual reports.

Of the corpses, 5,666 arrived from Saudi Arabia followed by 1,913 from the UAE and 1,893 from Oman.

The six GCC countries together hired 76.3 percent of Bangladesh’s total 1.6 crore outbound workers between 1976 and 2023, according to the Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training.

Many Bangladeshi migrant workers who died in the Gulf were at their young age, but there is a data deficiency on the underlying causes of the deaths, said Prof CR Abrar, executive director of RMMRU.

Most of the workers migrate abroad at the prime of their health conditions, as certified by the mandatory medical check-up at home before flying, he told this newspaper over phone.

However, they pay a hefty migration cost and face “ill-treatment” that together with a whole range of other factors could augment their physical and mental stress. In spite of the odds, they want to stay back to recoup the invested money, he added.

The VSP report says despite the lack of data, it appears that as many as 10,000 migrant workers from south and southeast Asia die in the Gulf every year.

More than one out of every two deaths are effectively unexplained, which is to say that deaths are “certified without any reference to an underlying cause of death”, instead using terms such as “natural causes” or “cardiac arrest”, it says.

In the six GCC countries, migrant workers occupy the vast majority of the jobs in low-paid sectors such as construction, hospitality and domestic work, it adds.

Bangladesh as an origin-country should press the destination countries to follow the World Health Organisation guidelines for a proper record of the cause of migrant deaths, said Prof Abrar.

“This is the minimum thing that we can demand,” he said, adding that such issues can be dealt bilaterally or addressed at regional forums like the Colombo Process or Abu Dhabi Dialogue.

Alongside emergency cases, the Gulf countries need to ensure treatment of migrant workers and their access to medical facilities in case of non-emergency health problems, he added.

The death of young migrants can have multiple ramifications, including compensation for their families, he further said.

However, it becomes difficult to contest the cases legally since evidence remains at the disposal of the destination countries, Prof Abrar added.

Contacted over phone, Shoaib Ahmad Khan, director (finance and welfare) of WEWB, said while deaths of migrant workers abroad are not expected, at their end, they provide Tk 3 lakh each in compensation to the families of deceased migrant workers and Tk 35,000 for carrying and burial at home.

Besides, deceased migrant workers’ families can claim a maximum of Tk 10 lakh under a mandatory insurance coverage depending on the nature of death, he added.

The Daily Star