Syed Badrul Ahsan

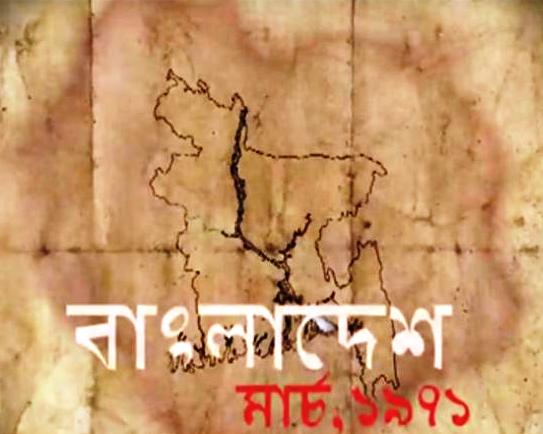

The terse, grim words went out, ‘Big bird in the cage. Little birds have flown.’ It was from a Pakistan army officer to his superiors in Dhaka cantonment. It was about the arrest of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in the early hours of March 26, 1971 soon after the Bengali leader had declared the independence of Bangladesh. Moments earlier, as March 25 drew to an end, the Pakistan army had launched its genocide of Bengalis through the misleadingly termed Operation Searchlight. Into the net were soon trapped academics and students, pedestrians and rickshawpullers, policemen and personnel of the East Pakistan Rifles. Thousands were done away with on that night. It was to be the beginning of a long nightmare.

As the genocide got under way, Pakistan’s president, General Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan, was preparing to land in Rawalpindi after a long circuitous flight over the Indian Ocean from Dhaka. In what had by then turned into an occupied Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was first taken to the under-construction national assembly premises and made to wait there until the military officers who had arrested him received instructions from their superiors on what to do with him. One of the officers asked Lt. General Tikka Khan, the martial law administrator, if he wished to have the Bengali leader brought to him. Tikka responded contemptuously, “I don’t want to see his face.” Mujib was eventually taken to Adamjee Cantonment College, where he would be confined for a few days until his flight to West Pakistan.

On the evening of 26 March, General Yahya Khan addressed the unsuspecting people of Pakistan on the developments that had taken place. Even as Pakistan’s citizens, in both wings of the country, waited to hear the president spell out the details of what they thought would be a transfer of power to the elected representatives of the people, the military ruler stunned everyone with news of the crackdown in East Pakistan. Mujib was accused of treason. The Awami League was charged with conspiracy to break up Pakistan. “This crime,” roared the general darkly, “will not go unpunished.” The next day, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, retrieved by the Pakistan army from Dhaka, landed in Karachi. He gushed to waiting newsmen, “Thank God, Pakistan has been saved.” A day after that, in distant Chittagong, a Bengali major in the Pakistan army, Ziaur Rahman, announced Bangladesh’s independence on behalf of ‘our great national leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.’ Meanwhile, senior Awami League leaders, students and citizens of all classes and professions were finding their way out of Dhaka and towards safer climes in the villages and small towns of the new country.

The declaration of independence precipitated a whole range of activity across the globe. Simon Dring’s reports on the first night of the massacre made the rounds in London and elsewhere, revealing the ferocity with which the Pakistan government had gone after the Bengalis. In early April, even before any formal arrangements were in place for a prosecution of the war of liberation, two Bengali diplomats posted at the Pakistan mission in Bombay, K.M. Shehabuddin and Amjad Hossain, declared their allegiance to Bangladesh. At around the same time, Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny wrote to President Yahya Khan, asking him to reach a political settlement with the elected political leadership in East Pakistan. Yahya’s response was an angry one. He denied the government was doing anything wrong. It did not help his regime, though, that Bengali refugees in their thousands were crossing the border into India every day as a way of escaping the wrath of his army. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called for the detained Mujib to be guaranteed safety. Bengali rebels, though, were doing things slightly differently: they kept up the refrain of Bangabandhu being free and directing battles against the Pakistanis. The worry, however, was that Mujib might already have been murdered by the army. For its part, keen to expose the hollowness of the rebels’ claim of Mujib being free, the Pakistani regime released the picture of a Mujib in police custody at Karachi airport. That was sometime before mid-April. No other information was given.

And yet, at the time, senior Bengali politicians, all Mujib’s close associates — Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, M. Mansoor Ali, A.H. M. Quamruzzaman — gradually and painstakingly linked up with one another. By 12 April, Tajuddin Ahmed had a rudimentary governmental structure for Bangladesh in place. But it was not until 17 April that a formal announcement of the formation of a provisional government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh would be made at a spot in Meherpur, Chuadanga. The place was named Mujibnagar. With Amirul Islam, the lawyer responsible for the draft of the Proclamation of Independence, working overtime to ensure the presence of the global media on the occasion, the first Bengali government in history went to work. Tagore’s Amar Shonar Bangla was sung (it would eventually be adopted as Bangladesh’s national anthem) and Colonel Mohammad Ataul Gani Osmany, commander in chief of the Bangladesh Mukti Bahini, supervised the guard of honour. Professor Yusuf Ali read out the Proclamation of Independence, which acknowledged the primacy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the president of the republic. In his absence, Syed Nazrul Islam would be acting president. And Tajuddin Ahmed would take charge as prime minister.

News of the arrival of Bangladesh’s first government was disseminated before the world. And then came more news — that Hossain Ali, Pakistan’s Bengali-speaking deputy high commissioner in Calcutta, had switched his allegiance to Bangladesh along with his fellow Bengali officers. The mission premises came under his control. Diplomats of West Pakistani origin were barred from entering the premises. Across the globe, as the army killed increasingly bigger numbers of Bengalis and as the number of refugees crossing into India swelled, media and popular opinion condemned Pakistan. The Soviet bloc made unmistakable signs of supporting the Bengali cause. In India, the government came in with material and moral support for Bangladesh. Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury moved from Geneva, where he had gone before the crackdown to attend a human rights conference, to London. His presence lent additional weight to the cause abroad. Expatriate Bengalis gathered around him; and he quickly became an authentic voice for Bangladesh in Europe.

Certainly there were those who did not sympathise with Bangladesh’s people. President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger, using Pakistan as a conduit to America’s opening with China, looked the other way as the Pakistan army went on raping and killing in Bangladesh. The left-leaning Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani’s appeals to China for support for the Bengali struggle went unanswered. Pakistan’s ambassador to Beijing (or Peking as it then was), Khwaja Mohammad Kaiser, a member of Dhaka’s Nawab clan, was in a dilemma. Prime Minister Zhou En-lai told him he understood his difficulties (in post-1971 times, Kaiser would return to Beijing, as Bangladesh’s ambassador to that country).

Things were different in Europe. In Britain, Prime Minister Edward Heath, Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home and opposition leader Harold Wilson comprehended popular feelings and appreciated Bangladesh’s stand. But circumspect was what they were, in line with the conventions of diplomacy. In France, Andre Malraux, formerly minister for culture in Charles de Gaulle’s government, expressed his intention of forming an international brigade to help the Mukti Bahini. The media in Africa, in such Middle Eastern nations as Egypt and in Indonesia kept up a barrage of news reports and editorial comments on the deteriorating situation in Bangladesh. George Harrison’s concert for Bangladesh at New York’s Madison Square Garden in August 1971 injected fresh new energy into the struggle and brought the urgency of the Bengali struggle closer to the West. For its part, the Mujibnagar government sent out its envoys — Abdus Samad Azad, Mohiuddin Ahmed and others — to Europe with the message of liberation. Bengali diplomats defected in droves and linked up with the Bangladesh movement. Some did not, and would not, until the last few weeks of the war. Some would stay loyal to Pakistan, until Pakistan felt it had little use for them (and that was after its army had been defeated on the battlefield). The Bengali cause was boosted when a non-Bengali Pakistani diplomat, Iqbal Athar, denounced his country and came over to Bangladesh.

At home, the Mujibnagar government, strengthened by the arrival of civil servants and soldiers, worked overtime to guide the nation to freedom. The Mukti Bahini boasted the presence of capable Bengali officers — Khaled Musharraf, K.M. Shafiullah, Ziaur Rahman, A.K. Khondokar, Abu Taher, C.R. Dutta, Nuruzzaman, et al — and operated in eleven sectors. Shwadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, the radio outfit of the government, was peopled by leading Bengali media and cultural personalities and broadcast stirring messages of hope and endurance to the nation. Periodicals like Joi Bangla carried the message of liberation into occupied Bangladesh. Ten million Bengalis, of a total population of seventy five million, were already in India as refugees. In August, the Pakistan regime put the incarcerated Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on trial for waging war against Pakistan. In September, Abu Sayeed Chowdhury led the Bangladesh delegation to the United Nations General Assembly. But he was not permitted to address the body. In November, Indira Gandhi travelled to Europe and the United States to explain India’s position on Bangladesh.

On 3 December, after Pakistan’s air force raided targets in India on the western sector, New Delhi went into full-scale war with Islamabad. An Indo-Bangladesh Joint Command pushed deeper into occupied Bangladesh. In the west, the Indian army gained swathes of territory in Pakistan’s Sind and Punjab provinces.

On 16 December 1971, 93,000 soldiers of the Pakistan army, led by Lieutenant General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, surrendered to the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army at the Race Course in Dhaka. Bangladesh was a free people’s republic. And yet the price its people paid in the struggle for freedom would be unprecedented in the annals of history. Three million Bengalis would be murdered by the Pakistani forces; and two hundred thousand women would be raped by the soldiers. On the eve of victory, an entire body of Bengali intellectuals would be rounded up by the local collaborators of the army and murdered in gruesome manner. The landscape would be littered with broken bridges, burnt-out villages and ruined towns.

source: bdnews24

all nonsense

hey days of Mir Jaffer