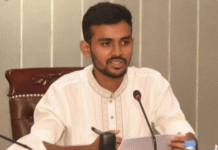

Man of integrity, politician of conviction

Why Tajuddin Ahmad is an indelible part of history

As General Yahya Khan prepared to travel to Dhaka in mid-March 1971 for talks with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his team, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto cautioned him about Tajuddin Ahmad. The most dangerous man in the Awami League, the chairman of the Pakistan People’s Party told the president of Pakistan, was Tajuddin.

Bhutto did not exactly define the meaning of danger associated with the Awami League general secretary, which Tajuddin was at that point. But that Tajuddin Ahmad was to be feared in any encounter between his party and the military regime and between the Awami League and the People’s Party was a harsh reality Bhutto could not afford to ignore.

Bhutto had good reason to be cautious where dealing with Tajuddin Ahmad was the issue. After all, he remembered only too well his challenge to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to a debate over the latter’s Six Points in early 1966. As foreign minister in the Ayub Khan government, albeit one soon to depart, Bhutto demanded that Mujib debate him on the Six Points at the Paltan Maidan in Dhaka.

Bangabandhu did not deign to respond. But Tajuddin did. He would, said he, debate Bhutto at the Paltan Maidan. In the event, Bhutto did not turn up. Tajuddin’s political acumen and intellectual height were enough to make him go silent. It was this he remembered in March 1971.

As the nation prepares to observe the anniversary of the birth of Tajuddin Ahmad — he was born in the year Deshbandhu CR Das died — it is only fitting and proper that we recall the contributions of the man whose emphatic and selfless leadership steered us to battlefield victory in December 1971. Bangabandhu had been seized by the Pakistan army and spirited away to what was then West Pakistan.

It was in the absence of the Father of the Nation, empowered by his inspiring leadership, that Tajuddin Ahmad launched the guerrilla struggle against Pakistan. On his way to exile in India, Tajuddin’s mind was less exercised by thoughts of shelter and more by the paramount need of building resistance to the occupation army.

Time, he knew, was of the essence, a reason why he met Indira Gandhi and solicited Delhi’s support for the coming struggle. He was also aware that resistance needed to be organized in the form of a government. It was a task he performed in remarkable manner, through bringing his senior party colleagues together and giving form and substance to a government-in-exile.

At Mujibnagar, as prime minister, Tajuddin Ahmad did not have the luxury of leading the struggle undisturbed. Assailed by the young elements in the party, many of whom were opposed to his leadership, and attacked by other leaders in the party, Tajuddin remained unfazed. Courage of conviction, a trait which had been building up in him since his days as a student of Dhaka University, defined his approach to the opposition he was confronted with.

Not even a vote of no-confidence shook him. He tided over that challenge. And then came the next challenge, that of thwarting Khondokar Moshtaq Ahmed in his ambitions of travelling to New York and repudiating the struggle for liberation in favour of a confederation with Pakistan.

There was poise in Tajuddin’s actions. If the enemies arrayed against him, caused him psychological anguish, he did not show it. He toured the border regions, visiting the millions of refugees streaming in from occupied Bangladesh. He was constantly on tours of the war zone, imbuing the young soldiers of the Mukti Bahini with patriotic zeal. His confidence in ultimate national victory was infectious.

More than four decades after he was murdered, along with three colleagues who had been part of the Mujibnagar team, it is Tajuddin Ahmad’s principled politics which continues to define him and which has assured him a place in national history.

In the period following Bangabandhu’s return from incarceration in Pakistan and assumption of the office of prime minister, Tajuddin Ahmad performed admirably as finance minister. He was unwilling to have the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund infiltrate Bangladesh’s economy, the better to have the new country avoid falling into the debt traps traditionally set by the Bretton Woods institutions.

At a conference in Delhi in early 1972, he studiously avoided meeting Robert McNamara for a couple of reasons. In the first place, his antipathy to the World Bank, which McNamara headed at the time, militated against such a meeting. In the second, he had not forgotten the disaster McNamara, as US defense secretary in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, had caused in Vietnam.

It remains a sad irony that it was the very same McNamara who a few years later welcomed Tajuddin in Washington in different circumstances. Bangladesh’s economy was in trouble, caused not a little by the ravages left by war and the exorbitant rice in global fuel prices in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Tajuddin could not have been happy with his trip to Washington.

One of the saddest aspects of independent Bangladesh’s history has been, and will be, the rupture between Bangabandhu and Tajuddin. Policy differences widened the chasm between these two men whose united approach to Bengali politics in the 1960s had reconfigured national aspirations.

But Tajuddin Ahmad’s loyalty to his Mujib Bhai remained unflinching and was without blemish till the brutal end to his life in November 1975. Earlier, towards the end of July of the year, having received a late phone call about an imminent threat to the life of the Father of the Nation, Tajuddin rushed off to Dhanmondi 32, half on foot, half by rickshaw, to warn Bangabandhu of the necessity of security measures for himself. A supremely confident Bangabandhu waved his concerns away, asked him not to worry and sent him back home. Tragedy struck barely a fortnight later.

As he was being taken away to prison by soldiers in August 1975, Tajuddin was asked by his wife Zohra how long he expected to be in jail. Tajuddin turned to look at her, telling her calmly: “Take it as forever.”

He did come back home two and a half months later, shot and bayoneted to death in the prison of a country he had guided to freedom three years and 11 months earlier.

A committed socialist, a man of profound integrity, a political leader possessed of sublime intellectual prowess, Tajuddin Ahmad is an indelible part of history.

He was only 50 years old when foul conspiracy silenced him for all time.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a journalist and biographer.