India-Bangladesh Relations: Risks of a Fallout Over the NRC

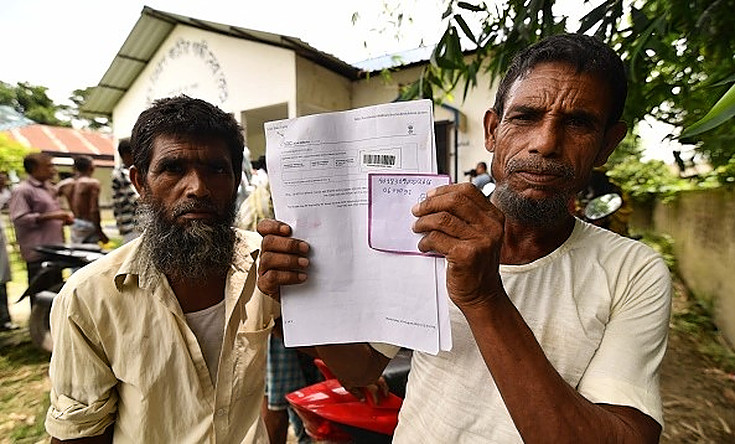

November 14, 2019 by Indrajit Sharma When Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina met her Indian counterpart Narendra Modi in New Delhi last month, she raised concerns over the National Register of Citizens (NRC), India’s attempt to identify “illegal immigrants” in the northeastern state of Assam that borders Bangladesh. These comments are only the most recent in a string of statements since the Bangladesh government first publicly expressed apprehension over Assam’s NRC process in July. Public discourse in India generally equates “illegal immigrants” with “Bangladeshis,” due to a large influx of refugees into India fleeing violence during and after the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, and Indian politicians belonging to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have termed them “infiltrators.”

Though New Delhi has attempted to assuage Dhaka’s concerns by conveying that the NRC is India’s internal matter, Bangladesh is worried that it may have to deal with the adverse effects of this decision, such as a potential influx of immigrants from India. India-Bangladesh relations have already been strained recently due to Bangladesh’s perception that India isn’t doing enough to support efforts to repatriate Rohingya refugees as well as the continued issue over sharing the waters of the Teesta River. Ever since Sheikh Hasina was sworn in as Prime Minister of Bangladesh in 2009, India-Bangladesh relations have been on an upward trajectory and reached unprecedented heights with an evolving strategic partnership. However, the NRC issue threatens to thwart this progress in bilateral relations between India and Bangladesh. Though New Delhi has attempted to assuage Dhaka’s concerns by conveying that the NRC is India’s internal matter, Bangladesh is worried that it may have to deal with the adverse effects of this decision, such as a potential influx of immigrants from India.

Bangladesh’s Anxiety over the NRC

Bangladesh is concerned about a potential influx of immigrants from India largely due to it already being burdened with Rohingya refugees who are unlikely to be repatriated back to Myanmar. Despite already having the ninth-highest population density in the world, Bangladesh is currently hosting over 900,000 Rohingya refugees living in camps and is in no position to receive further immigrants. Without adequate funding from donor countries, the socio-economic impact of the Rohingya influx is visible in Bangladesh, which faces increased levels of poverty and strains on infrastructure. Further, since the Rohingya continue to be seen as outsiders in Bangladesh, there have been sporadic clashes between host communities and the refugees, which have the potential to escalate in the future. Bangladesh fears it would face a similar situation if it has to house the population excluded from the NRC list.

Moreover, any possible influx following the completion of the NRC process would not only add to Bangladesh’s problems but could also bolster the radical elements in the country, such as Jamaat-e-Islami, who want to discredit Prime Minister Hasina. Soon after Hasina signed several agreements with India during her October visit, the Senior Joint Secretary General of Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) demanded that she immediately step down for signing “anti-state” agreements and “ignoring [Bangladesh’s] national interest.” Although Hasina defended the agreements, her government is consistently under pressure from a domestic audience that sees her as pro-India and questions her credibility in dealing with the country. For instance, after the bilateral meetings at the foreign secretary-level in April 2018, the opposition criticized Hasina’s government for failing to reach an agreement with India on the Teesta River water-sharing issue. In light of this, the Hasina government feels even more pressure to prevent the opposition from exploiting the NRC issue with India for its own political advantage.

Why New Delhi Must be Careful Not to Alienate Dhaka

If India is not careful, the NRC issue could derail its relationship with Bangladesh, squandering years of economic and strategic goodwill it has built. With common economic and strategic interests, contemporary India-Bangladesh relations are wide-ranging. Bilateral trade reached nearly USD $10 billion at the end of fiscal year 2019 and, for the first time in 2019, exports from Bangladesh to India exceeded USD $1 billion. In the strategic domain, the two countries’ resolve for zero tolerance towards terrorism and violent extremism has been significant for regional peace, security, and stability.

India’s regional interests compel it to maintain strong relations with neighbor Bangladesh, which holds considerable geopolitical weight for New Delhi. Hasina’s government has been crucial in the past for tackling internal security challenges facing India’s Northeast. Hasina’s efforts to reduce terrorism and extremism in Bangladesh in the wake of the Holey Artisan cafe attack have increased security and stability not only in her own country, but also reduced cross-border terrorism into India. Further, unlike the BNP, Hasina’s government does not play up hostility towards India for political gain. If the ongoing developments over the NRC produce a tenuous relationship between the present Bangladeshi government and India, the BNP and its ally Jamaat-e-Islami—both of which are ideologically opposed to India—could use the NRC issue as a reason to increase support for terrorist groups in northeast India. To continue to strengthen the improved security situation in the region, India needs Bangladesh’s cooperation to reduce the looming threat of terror on its borders.

Additionally, as Bangladesh is an emerging “hub for connectivity,” it is a significant ally for India’s connectivity drive towards the East. Enshrined in its Act East Policy, India has been adapting its economic and foreign policies in its near and extended neighborhood to counter growing Chinese presence in the region. China recently became the main source of imports in Bangladesh and is the country’s largest trading partner. Further, China has invested around USD $10 billion in Bangladesh as part of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. Particularly, the development of ports in Bangladesh as part of BRI presents China with an opportunity to gain access to deep sea ports in the Indian Ocean. China’s influence in Bangladesh raises concerns for India’s strategic interests in South Asia and the Indo-Pacific region. If India wishes to counter China’s presence in South Asia and to spread its influence into Southeast Asia, then India will need to ensure that its relations with Bangladesh do not sour over the NRC issue. If India wishes to counter China’s presence in South Asia and to spread its influence into Southeast Asia, then India will need to ensure that its relations with Bangladesh do not sour over the NRC issue.

Due to the aforementioned stakes, any mishandling of its bilateral relations with Bangladesh would be counterproductive for India. Given that Bangladesh currently categorizes its bilateral relations with India as “the best of the best,” Bangladesh hopes that India would not send the people excluded from the final NRC list across the border into Bangladesh. However, in the absence of a clear policy pertaining to the fate of these people, India faces mounting domestic and international pressure to specify what the future holds for the approximately 1.9 million people excluded. India would have to carefully craft an answer that encompasses the concerns of the various stakeholders involved in the tangled issue of the NRC. To ensure that the NRC is handled in a way that is sensitive to regional dynamics, India needs to maintain dialogue with Bangladesh in order to not jeopardize current diplomatic ties and avoid any potential fallout from the NRC.

Indrajit Sharma

Indrajit Sharma is associated with South Asia Terrorism Portal at the Institute for Conflict Management, a New Delhi based think tank focusing on Conflict and Terrorism in South Asia. He holds an M.Phil. and a Ph.D. in Security Studies from Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, India. His research interests include ethnic conflict and insurgency in Northeast India, migration/refugees and national security, conflict management and resolution, security and development. Previously, he worked as a Guest Faculty at the Raksha Shakti University (First Internal Security & Police University of India), Ahmedabad. He can be contacted at meetindr@gmail.com.

The article appeared in the southasianvoices.org on 17 November 2019