‘Republic’ as the synonym of ‘a state governed by subjects’ is a bit confusing. If a state is governed by elected representatives of subjects, then the subjects must control the decision making. On the other hand, a republic actually defines a state system governed by citizens who can exercise some constitutional rights, contrary to the subjects of a monarch.

People of a republic are used to identifying themselves as citizens, not subjects, because the term ‘subject’ is much more relevant to monarchy.

Hence, defining a ‘republic’ formed by ‘subjects’ is contradictory. It seems that the term ‘republic’ cannot represent the real scenario.

Similar to people of other countries, our ancestors were too were subjects ruled by monarchs. They would only enjoy the rights their kings kindly allowed them. This system came down from before the colonial era and even existed in the British rule. Once, the kings were sovereign. The Mughal emperors limited the sovereignty of the local kings by taking their estates under control one after another, but never restricted the kings from using the ‘raja’ title. Even the zamindars (landed gentry) under the control of provincial nawabs used the aristocratic ‘raja-maharaja’ titles. Maharaj Krishnachandra–famous for his court jester Gopal Bhar–was actually the zamindar of Nadia under the rule of Nawab Sirajuddaula. This system prevailed in the British Empire too. The British rulers comparatively were more authoritarian. During the Mughal regime, a provincial governor was honoured as subedar and the chief commander of the army as well. The British rulers all of a sudden changed the designation as a junior commissioned officer or JCO, a post lower than lieutenants.

During the British rule, subjects used to honour the zamindar by calling him ‘maharaj’, and wife ‘rani’. They considered the zamindar’s residence as the ‘rajbari’ (the king’s house).

Given the natives a limited access to politics in British India, only two political parties–the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League– could flourish prominently. But the parties were not led by subjects. Only elites and wealthy people controlled the parties. There were people with communist philosophy to uphold the interests of peasants and workers, but their political activities were limited.

Pioneering the politics of the Bengal masses, Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Haque-led Krishak Praja Party garnered wide-spread popularity. Despite having a highly educated and rich man at the top, the party prioritised the subjects in Bengal while setting its political agenda. As a result, AK Fazlul Haque became the first elected prime minister of the undivided Bengal, defeating contenders of the two big political parties. Following the end of British rule in India, the subjects at last gained ownership of their land after the enactment of East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act in 1950.

People of the East Bengal still continued struggle to access citizen rights in the post-partition Pakistan era. The final stage of the struggle was the Liberation War 1971. The political elites of Pakistan, like the ancient kings, considered the East Pakistanis as their subjects. The new rulers never admitted that East Pakistanis were also entitled to the citizen rights equally. They carried out the 25 March massacre to make the East Pakistanis their subjects permanently. But they had to quit the land permanently after their defeat in the Liberation War.

George Bernard Shaw wrote a pleasant play, Arms and the Man. During the concluding part of the play, Bluntschli is trying to convince Raina’s Bulgarian father Petkoff by giving a description about his wealth. Petkoff, with great surprise, questions, “Are you Emperor of Switzerland?”

Bluntschli replys, “My rank is the highest known in Switzerland: I’m a free citizen.”

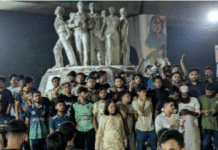

After the Pakistani occupational army’s ultimate defeat and their exit from Bangladesh, we, as the citizens of the newly independent country, felt honoured like Bluntschli, though, we had no wealth like his. Our feelings did not last for long. Authoritarianism, like a disease, infected many of the politicians. The new rulers of Bangladesh too started to consider the masses as their subjects.

People born during in the 1960’s, can still remember the two-lane concrete roads in Dhaka city of that time. The open places by the roadsides were mostly covered with green grass. There were a few cars in the newly independent Bangladesh. One day, a junior government officer was plying through Dhaka streets in an old-fashioned jeep. At once, a small motorcade was honking from behind. For whatever the reason was, either driven by ego or stupidity, the jeep driver initially did not give the motorcade space to overtake. After a while, a car from behind overtook the jeep, stopped in front of it and eventually blocked the jeep’s way. A certain important personality was sitting inside the car. His peers came out from the car, dragged out the jeep driver forcibly and beat him up mercilessly as if they taught the jeep driver a good lesson for his disrespect. The important person inside the car remained silent.

Recently, I noticed a newspaper report about some supporters of an important and powerful political figure beating up two persons as they refused to leave a ferry that their cars boarded. The attackers claimed that the ferry was ‘reserved’ for their large motorcade led by the political figure. One of the injured persons said the attackers would have killed him unless he was rescued by local people and police.

According to the news report, the victim said he was not willing to take legal actionsagainst the muscle power, fearing harsh consequences. He, being a subject, took a realistic stance.

Fifty years of independence has elapsed. How much longer will it take us to upgrade from subjects to citizens?

*Md Touhid Hossain is a former foreign secretary

* This opinion appeared in the print and online versions of Prothom Alo, has been rewritten in English by Sadiqur Rahman