Like bunches of blood-red Oleander, Like flaming clouds at sunset

Asad’s shirt flutters

In the gusty wind, in the limitless blue.

[Asad’s Shirt (Asader shirt) Translated by Syed Najmuddin Hashim]

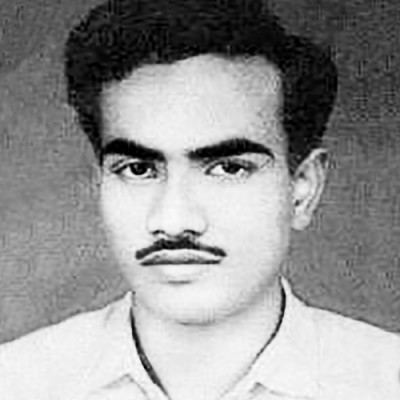

Poet Shamsur Rahman wrote these immortal lines on the martyrdom of Asad, a young left-leaning student activist who died in a police firing on January 20, 1969. His death triggered a mass uprising that transformed Dhaka into one of the sites of the global sixties. Like Paris, Mexico City, Beijing, Prague, Hanoi, Rawalpindi or nearby Kolkata, Dhaka also became a city of procession, anger and revolution. This outpouring of public grievance against a pro-western supposedly modernising military dictator had a long history in the making in the sixties.

The most pertinent aspect of Pakistan’s rule in Bangladesh was political-economic exploitation. Despite constituting a demographic majority in Pakistan, Bengalis constituted a minority in terms of representation in the army, bureaucracy and industrial houses. In the early 1960s, under praetorian guards, Pakistan was pursuing a process of capitalist modernisation in alliance with the United States. With massive aid from Western donors and encouragement from the US administration and Harvard-based American advisors, military rulers adopted a growth-oriented economic policy between 1958 and 1969. Yet such growth-oriented strategies were not accompanied by an attention to social equity. Therefore, in 1961 seventeen industrial houses from West Pakistan controlled 30 percent of gross fixed assets at cost and 20 percent of the total sales of large manufacturing sectors. Even in East Pakistan, six houses, namely Adamjee, Dawood, Karim, Bawani, Ispahani, and Amin, controlled 40 percent of the total assets in the manufacturing sector and 32 percent of the production in large-scale manufacturing sectors. [Amzad, Rashid “Industrial Concentration and economic power” in Gardezi, H. & Rashid, J. (ed.) Pakistan: The Roots of Dictatorship. London: Zed Press. 1983 : 232.] Except for Ispahani, originally a Kolkata-based trading house of Iranian origin, all these groups belonged to either Karachi-based Gujarati immigrant families or Punjabi families. In the fifteen years between 1949-50 and 1964-65, the manufacturing sector of Pakistani industries increased by nearly 15 percent per year. However, the rate of increase in real per capita income in Pakistan was less than one percent per year. At the same time, it was observed that the level of per capita income was at least 30 percent higher in West Pakistan than in East Pakistan in 1964-65, though this difference had been only 10 percent in 1949-50. The net transfer of resources from East to West Pakistan, and the expenditure of only about one-third of Pakistan’s development resources in East Pakistan, led towards stagnation in the economy. [Thomas, John Woodward. “Development Institutions, Projects, and Aid: A Case Study of the Water Development Programme in East Pakistan.” Pakistan Economic and Social Review 12, no. 1 (1974): 77-103:78. Accessed June 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25824787.]Consequently, in the twenty-three years of United Pakistan’s existence, the per capita income of East Pakistan rose by only two dollars.

Politically, Ayub Khan tried to pepper over these contradictions by introducing a system of basic democracy in Pakistan. In 1959, 40,000 basic democrats were elected from East Pakistan, and 40,000 were elected from West Pakistan. Eight thousand units of Basic Democracy were created for electing ten members who, in turn, constituted the electoral college for the presidential election. Who were these basic democrats in East Pakistan? Rashiduzzaman provides a picture of the nature of rural society and the position of basic democrats in rural social hierarchy. In a survey of 3,675 members of the union board chairmen it was found that nearly 61.12 percent of chairmen had an annual income of Rs. 4,000 and above. Around 28.79 had an annual income between Rs. 2,000-4,000, and only 9.69 percent claimed an income less than Rs. 2,000 per annum. In this period, 85.7 percent of the rural population had an annual income of less than Rs. 2,000 per year. In terms of the size of their landholdings, nearly 42.40 percent of the basic democrats in East Pakistan had more than 13.5 acres of land. Around 40.41 percent of basic democrats had five to 7.50 acres. In terms of average rural landholding size in East Pakistan, 62.81 percent of basic democrats were holders of large farms. It can be concluded that large numbers of basic democrats were recruited from surplus farmers who could be classified as rich peasants. This coalition of rich peasants and monopoly industrial houses, presided over by the upper echelon of army and bureaucracy, established a process of internal colonial exploitation in East Pakistan.

Added to this was an absurd notion that the Bengali language was not a proper vehicle for articulating Muslim identity. Though after the student movement of 1952, the government of Pakistan recognised Bengali as a national language in 1956, the government did not promote the language equally with Urdu. The state promoted various schemes to transform the language and abstract Bengali from its rich heritage, including a proposed change to its vocabulary and script.

Throughout the sixties, contrapuntal literary and cultural efforts manifested in organised cultural activities and literary conventions. The partisans of Bengali culture and its heritage, spearheaded by communist-minded intellectuals, launched a form of cultural struggle against the regime. From a Gramscian perspective, these intellectuals engaged in a ‘war of position’ to undermine the state’s legitimacy. This cultural resistance slowly built up the strength of a newly imagined community of a linguistic nation by creating alternative intellectual resources. As articulated by Gramsci, issues of culture lay at the heart of a revolutionary project; culture crucially informs how people see their world and, more importantly, “it shapes their ability to imagine how it might be changed, and whether they see such changes as feasible or desirable”.[Crehan, K. 2002. Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology. 1st ed. University of California Press. p.71]

The decade of the sixties opened with a cultural introspection of Tagore’s legacy in East Pakistan. Three public committees had been formed to celebrate Tagore’s birth centenary, and they coordinated their activities under the leadership of Justice Syed Mahbub Morshed. Justice Murshid was not dissuaded from heading the centenary celebration despite pressure from the government. Tagore’s legacy in East Pakistan entered into crisis again in the wake of the India-Pakistan War. Radio Pakistan and television broadcasts stopped airing Tagore’s songs during the war because of their ‘Indian’ origin. But in 1967, the government decided to ban the airing of Tagore’s songs on Radio Pakistan, since his ideas were perceived to be contrary to Pakistan, on the order of the information and broadcasting minister, Khwaja Shahabuddin. Intellectuals organised a signature campaign on this statement. A statement by nineteen writers, scientists, painters, and teachers appeared in the newspapers on June 25, 1967. Under pressure from public opinion, minister Khwaja Shahabuddin announced that he did not consider Tagore’s songs to be opposed to the spirit of Pakistan but also qualified his statement by saying that he would consider restricting only those songs which directly contradicted the spirit of Pakistan. This was regarded as a victory by Tagore enthusiasts in East Pakistan.

In the 1960s, Dhaka city became a fertile ground for avant-garde cultural activities that questioned the framework of exclusivist religious nationalism. Communist cultural activists played a crucial role in such events. Srijoni Sahityo Gosthi, Kranti, Unmesh Sahityo o Sanskriti Samsad, and Udichi performed the role of pioneering cultural organisations in pushing the frontier of cultural resistance. Chhayanaut popularised Tagore and Nazrul’s work among the educated youth.

East Pakistan witnessed a transformation in poems, novels, and short stories’ themes, content, and writing styles throughout the sixties. The most notable shift was in the genre of poetic literature. A new crop of poets emerged who employed different imageries, metaphors, and poetic language. Foremost among them was the poet Shamsur Rahman, a graduate of English literature from Dhaka University in 1953, who steered Bengali poetry in a new direction. Through his magical lyrics, he transformed the quotidian drudgery of urban life, melancholy of sheer poverty, and even mundane objects like traffic lights into urbane and elegant verses. He also wrote the most profound political poems of the 1960s and early 1970s. In “My Sorrowful Alphabet,” he articulated his passionate repudiation of the proposition made by Justice Hamoodur Rahman Commission in the 1960s that Bengali could only be ‘integrated’ into the Pakistani nation if it were written in Arabic or Latin scripts. In many East Pakistani Bengali poems of the 1960s, critics discern the influence of the French 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire. Many poets shared a manifesto of sadness, and some of them believed that, like Baudelaire, there existed constant tussle between God and Satan, and humans had an indeterminate existence. Asad Choudhury, a student, published in Sambad a poem titled ‘Another hero of history’. It was written on Patrice Lumumba. Azad Sultan, a student writer, edited a special anthology titled ‘The rise of Sun in the heart of Africa’. In the words of Auritro Mazumder, a literary theorist, an insurgent “imaginaire” informed the revolutionary spirit.

Bengali novels, too, underwent a similar transformation in terms of themes and structure. Syed Waliullah’s Chander Amaboshay (Etiolating Moon) (1964) and Zahir Raihan’s Hajar Bochor Dhore explain the anatomy of rural life, poverty, class repression and the frustrations of the educated youth. Communist novelist Satyen Sen’s Podochihno (Footprint) (1968) explains life’s insecurity and slow transformation from prosperity to misery in a Hindu village in rural Bengal. Finally, Shahidullah Kaiser’s Sareng Bou (Wife of a Sailor) depicts the struggle of a village housewife against the designs of local rich peasants amidst the destruction brought on by a tidal wave in a seaside village. These landmark novels depict social transformation, class struggle, patriarchal dominance and the sad consequences of the partition.

A transformation took place in the world of movies. Movies that combined a folkloric mode with tales of rural lives in the 1960s made instant box office hits. Abdul Jabbar Khan’s movie Joar Elo (Tide Came) depicted a bucolic Islam, focusing on the mixture between supernatural and natural. Following Khan’s box office success, Salahuddin, who earlier made movies on urban life, turned to fairy-folk tales and made a movie called Rupban. A simple narrative based on the tradition of roving folk operas, called Jatra, proved to be an instant box office success. The return to folk narratives in the film was a reflection of what Fanon noted about the discovery of the roots of indigenous cultures in a colonised nation. The folk theme also influenced Zahir Raihan, the most versatile director of East Pakistan, to make another movie in 1966 based upon the folk tale of Behula. Though the story was associated with the ‘Hindu’ goddess Monosha, it was presented as a folk tale on celluloid screen, and it enjoyed significant commercial success.

These variously conjoined and conflicting cultural discourses have in common those processes by which the meaning of resistance is produced, grounded, and heightened. Reflexivity concerning the cultural resistance of the sixties, their methods, and their motives will be a politically eviscerated narrative if it abstracts real-life popular political processes through which impassioned students, workers, subaltern social classes and progressive political activists resisted praetorian capitalism and internal colonisation. Cultural processes were part of a wider popular political movement through which many were martyred for the sake of democracy and exploitation-free society.

Indeed, the global sixties manifested in East Pakistan through mass protests. The decade started with massive student protests in 1962 against the reports of the national education commission of Pakistan. Under the chairmanship of S M Sharif, a former professor of Aligarh Muslim University and secretary to the education department of the Pakistan Government, the report for privately paid education was submitted in East Pakistan. Yet students were alone in their stand against praetorian capitalism. The student movement in 1962 was followed by strikes among jute mill workers in 1964 and ’65. Soon former student radicals such as Kazi Jafar Ahmed, Haider Akbar Khan Rono and Rashed Khan Menon spearheaded the radical labour movement in Tongi industrial areas near Dhaka city. In February and March 1965, there were strikes among post and telegraph workers in both East and West Pakistan. In March 1965, workers in Chattogram and Chalna Port went on strike. After a much-prolonged campaign, railway workers struck work on May 27, 1965. Even nurses in the hospital struck work in May. These working-class struggles gave meaning to the student protests. However, it would be wrong to view the protests against the praetorian rule in a unilineal triumphal march. Indeed, the war between Pakistan and India brought a temporary halt to such protest movements.

After the war, on February 5, 1966, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman placed his six-point programme in the Lahore conference of opposition parties. He captured the imagination of the middle class in East Pakistan by proposing economic autonomy for the province. Meanwhile, in Dhaka, anti-social elements belonging to government-sponsored student organisation NSF beat up Marxist Professor of Economics Abu Mahmud. This sparked a prolonged student struggle. Subaltern social classes also voiced their anger with their economic situations. Auto-rickshaw drivers of Dhaka went on strike from March 1. It was against this background Sheikh Mujib organised a persistent campaign for the six-point programme demanding fiscal autonomy for the province. Despite his frequent arrests, Sheikh Mujib was able to draw attention to this demand charter in East Pakistan. On June 7, workers in Tejgaon and Narayanganj revolted against the clamping of Section 144 by the government and faced police firing. Nearly ten workers lost lives.

In 1967, threats of workers’ strikes paralysed the city. Jute workers, employees of self-administered state concerns and transport workers, went on strike. Maulana Bhashani also organised a convention of jute cultivators on January 27. From February 1, railway workers declared a continuous strike. Left-leaning National Awami Party (NAP) started agitating against inflation. Throughout 1967, different trade unions and segments of working classes announced their industrial action and challenged the hold of praetorian capitalism. By the end of the year, NAP witnessed a split, and a group of dissidents also left Awami League. Political protests against the military-bureaucratic regime started losing their dynamism. In such circumstances, on January 7, 1968, the government brought charges of treason against eight concerned personalities. On January 18, 1968, the government included Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and 34 other concerned individuals within the purview of this act. On October 19, in a council meeting, Awami League decided to boycott the basic democracy election, demanded the dissolution of one unit in West Pakistan and asked for the introduction of an election based on the population ratio. These decisions brought Awami League and Bhashani-led NAP to cooperate with each other. In the meantime, on November 26, 1968, students revolted in Rawalpindi against the Ayub Khan regime.

In the December of 1968, Maulana Bhashani started protests against the government by declaring a total strike. On December 6, he started a blockade of the Governor’s house after a successful public meeting. The province witnessed another hartal on December 8. On December 10, 1968, opposition political parties observed an anti-autocracy day. Bhashani moved further on December 14 by organising a gherao movement. The idea was to paralyse the administration by surrounding the offices with political workers. On January 4, 1969, student organisations formed an 11-point programme. On January 8, 1969, eight political parties, including Awami League and NAP (Muzaffar), formed the Democratic Action Committee (DAC). All these forces demanded a federal form of government, election based on universal adult franchise, and release of all political detainees. On January 14, 1969, DAC announced its demand charter. On the same day, Bhashani addressed a peasant gathering in Hatirdia. On January 17, DAC organised a procession from Baitul Mukarram mosque. But students organised more militant processions and clashed with police forces. Consequently, there took place massive student meetings in Bottola in the Arts complex of the University, and students organised processions and clashed with police. Students decided to observe strikes against police atrocities throughout the province on January 18.

On January 20, 1969, students were well-prepared. They clashed with the police and closed the University gate with roller and concrete slabs. As the police started beating them with staves, students threw stones and bricks. During such clashes, retreating police forces were fired, and at that moment, Assaduzaman, a student union activist (Menon fraction), died in the police firing. His death transformed the political circumstances. Subaltern social classes, students, cultural activists and political workers observed spontaneous strikes, held massive meetings and organised processions from January 24 onwards. Again on January 24, Matiur, a young student of class IX, died in police firing. Movement for democracy, regional autonomy and a linguistically free nation produced more martyrs. The military even killed Sergeant Zahrul Huq, an under-trial prisoner in the Agartala Conspiracy Case, on February 15, 1969. On February 18, 1969, Dr Mohammad Shamsuzzoha, the Proctor of Rajshahi University, was killed. This increased the resolve of the people. Maulana Bhashani threatened to launch a no-tax campaign. Faced with mass political unrest, the government dropped the charges against Agartala conspiracy case detinues on February 22, 1969, and unconditionally released Sheikh Mujib the next day. Unnerved by mass unrest, army top brass became restive, and finally, on March 25, 1969, Ayub Khan resigned from the position of President of Pakistan.

The martyrdom of Assaduzaman symbolised the culminating point of the global sixties. It was a decade of protests for democracy, social transformation and national emancipation from colonial rule. In Bangladesh, workers, students, writers, and cultural activists undermined a shambolic praetorian democracy and ended the internal colonisation in the name of development.

Subho Basu is an Associate Professor at the Department of History and Classical Studies at McGill University. He is currently completing his book on the emergence of independent Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star’s Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star’s Google News channel.