However, the cuts have spurred protests and criticism of past government policies, as well as calls for new policies.

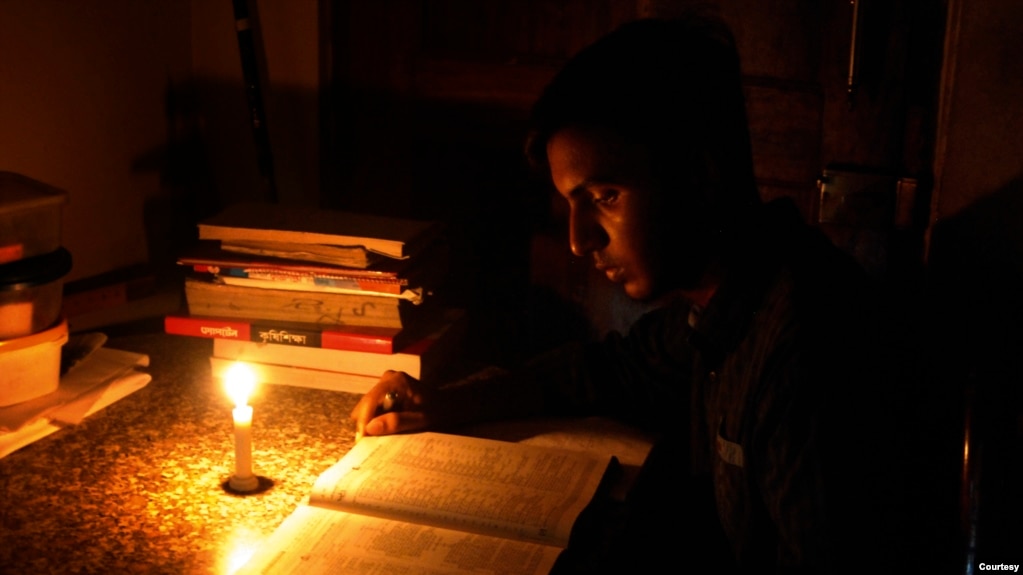

The shortage has brought back load shedding – the shutting down part of the grid to prevent failure of the system — which had become a thing of the past, in both cities and in rural areas. The renewed frequent outages have spurred expressions of anger and frustration in the street and social media.

“For the past few days, we had electricity for like five to six hours a day. It has become unbearable to live like this in this summer heat,” Hamidul Bhuiyah, a resident of the town of Sylhet in northeastern Bangladesh told VOA.

“I am wondering whether we are facing a crisis like Sri Lanka,” said Bhuiyah, who came down onto the street on Wednesday night to protest the outages in his Dakkhin Surma neighborhood.

While Bhuiyah protested on the street, economics professor Anu Muhammad expressed his frustration on his Facebook page.

“I didn’t have electricity in my house even when the government lavishly celebrated the 100% electrification of the country through fireworks in Dhaka’s Hatirjheel area.”

Muhammad was referring to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government’s celebration of making electricity available to 100% of the country’s population in late March. Hasina, in power since 2009, has long boasted about solving the electricity crisis that plagued the nation just a decade ago.

Questioning that success, Muhammad — known for his fierce advocacy of protecting Bangladesh’s natural resources from foreign control — said the electricity crisis was long in the offing and had happened because of some of the government’s faulty policies, such as not exploring Bangladesh’s own resources through a state-owned company.

Triggered by war

Hasina, meanwhile, said her government is finding it increasingly difficult to keep power plants running as operational costs continued to spiral in the face of the war in Ukraine.

“Prices have gone up to such an extent that it has now become difficult to keep the power plants running with the gas we have in stock,” she told a virtual program on Thursday.

Fifty-two percent of Bangladesh’s electricity is produced from natural gas, whose declining domestic production has been supplemented by liquefied natural gas imports. However, sharp price increases in the global LNG market have forced a halt in purchases for now.

After the Russian invasion, Europe announced a plan to reduce its dependence on Russian gas by buying LNG from elsewhere. This new competition for limited global LNG supply has quickly driven prices up.

LNG accounts for 20% of Bangladesh’s gas supply to power plants, and the country last paid $25 per MMBtu – LNG is measured by MMBtu, or million British thermal units — but the price is now $40 per MMBtu in the global spot market.

According to Bangladesh’s Power, Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry data, on average 3.1 billion to 3.2 billion cubic feet per day of gas has been distributed across the country since the beginning of the year. But for the last week, the average supply was 2.8 billion to 2.9 billion cubic feet, a drop of more than 10%.

Energy experts are predicting that LNG prices could increase further this year as European countries will likely buy more LNG for winter.

Hasina thus urged people to be cautious in using power and said she is considering reducing power production for some time to save fuel.

Her government will implement additional steps through executive order, including shortening office hours, not setting air-conditioners below 25 degrees in offices, reducing the use of air conditioning in religious establishments like mosques, and ending weddings and other social events by 7 p.m.

Experts said such rationing might bring some relief in the short run but that the government needs to revamp its energy and power policy for a long-term solution.

“It’s not that the power crisis of Bangladesh will be resolved in a week or two,” said Shamsul Alam the current energy adviser of Consumer Association of Bangladesh.

“It’s here to stay for some time,” Alam told VOA.

Like economist Muhammad, Alam believes the country’s current electricity crisis is taking place not just because of war or a global energy crunch but is partly the responsibility of the Hasina administration.

“We have already put too many eggs in one basket, as our power production is heavily dependent on natural gas. The reserves in the gas fields are declining and the government, instead of focusing on new gas field explorations, opted for costly LNG imports,” he said.

Alam said such dependency on LNG imports is dangerous given volatile international market prices.

“Our government should have opted for a better energy mix to reduce the dependency on a single fuel,” Alam added.

Relief in September

Hasina’s energy adviser, Tawfiq-e-Elahi Chowdhury, meanwhile told a news conference Thursday that the current power crisis is likely to continue until September, but after that some coal-burning power plants will be connected to the national grid, which could bring relief.

About 8% of the country’s electricity production capacity of 22,066 megawatts comes from coal, and Bangladesh has plans to significantly increase that percentage.

In the last year, Bangladesh canceled plans to build 10 coal-burning power plants but construction of some of large plants is going on and on course to be completed soon.

Chowdhury said that by September, 1,200 megawatts of coal-based electricity is likely to be added to the national grid from a plant being built in India’s Jharkand state by India’s Adani Group. Another 1,320 and 700 megawatts will be added respectively from power plants in Bangladesh’s Rampal and Payra areas.

Arifuzzaman Tuhin, a journalist who has been covering Bangladesh’s energy sector for over a decade, however, told VOA that these large coal-burning power plants will not solve Bangladesh’s energy crisis in the long run.

“The cost of producing per unit of electricity from coal is already 13 cents but the government is selling electricity at 5 cents per unit. So, again, the government will have to inject a large subsidy to keep producing power from coal. I don’t think it’s sustainable,” he said.

Tuhin said Bangladesh lacked a holistic approach in handling the energy and power sector.

“For example, we have created a 22,000-megawatt capacity system but could transmit and distribute only 60% of it now.”

“Rather than focusing on transmission and distribution, the government was keen on spending more on power generation. Because of this, we now have to make billions of dollars’ worth of capacity payments for idle plants,” he added.

Under the terms of its various agreements with power producers, the Bangladesh government pays the latter what’s known as a capacity payment, meant to ensure electricity is always available on tap, even if it means paying them to remain idle.

According to the annual report of state-owned Bangladesh Power Development Board, for the 2020-21 fiscal years, the capacity charge paid to 37 private power producers was about $1.35 billion.

“Such large payments for practically nothing of course put a big dent on the government’s purse. No surprise there that a price escalation in global fuel market thus force them to go for austerity measure,” Tuhin told VOA.