The European and Russian space agencies are to send a lander to an unexplored area at the Moon’s south pole.

It will be one of a series of missions that prepares for the return of humans to the surface and a possible permanent settlement.

The spacecraft will assess whether there is water, and raw materials to make fuel and oxygen.

BBC News has obtained exclusive details of the mission, called Luna 27, which is set for launch in five years’ time.

The mission is one of a series led by the Russian federal space agency, Roscosmos, to go back to the Moon.

These ventures will continue where the exploration programme that was halted by the Soviet Union in the mid 1970s left off, according to Igor Mitrofanov, of the Space Research Institute in Moscow, who is one of the lead scientists.

‘We have to go to the Moon. The 21st Century will be the century when it will be the permanent outpost of human civilisation, and our country has to participate in this process,’ he told BBC News.

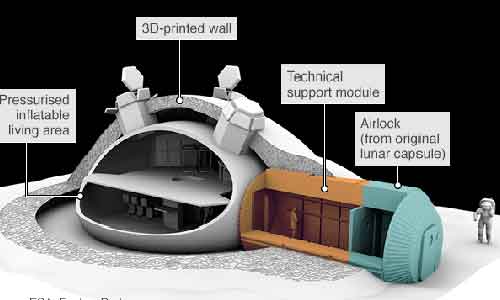

The European Space Agency’s vision for a Moon baseBut unlike efforts in the 1960s and 70s, when the Soviet Union was working in competition with the US and other nations, he added, ‘we have to work together with our international colleagues’.

Bérengère Houdou, who is the head of the lunar exploration group of at ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre, just outside Amsterdam, has a similar strategy.

‘We have an ambition to have European astronauts on the Moon. There are currently discussions at international level going on for broad cooperation on how to go back to the Moon.’

One of the first acts of the new head of the European Space Agency, Johann-Dietrich Wörner, was to state that he wants international partners to build a base on the Moon’s far side.

The initial missions will be robotic. Luna 27 will land on the edge of the South Pole Aitken basin. The south polar region has areas which are always dark. These are some of the coldest places in the Solar System. As such, they are icy prisons for water and other chemicals that have been shielded from heating by the Sun.

According to James Carpenter, ESA’S lead scientist on the project, one of the main aims is to investigate the potential use of this water as a resource for the future, and to find out what it can tell us about the origins of life in the inner Solar System.

‘The south pole of the Moon is unlike anywhere we have been before,’ he said.

‘The environment is completely different, and due to the extreme cold there you could find large amounts of water-ice and other chemistry which is on the surface, and which we could access and use as rocket fuel or in life-support systems to support future human missions we think will go to these locations.’

Back in the heady days of the Apollo missions, it seemed almost inevitable that those astounding but brief trips to the Moon would be followed by something more permanent. But the notion of colonies soon proved to be science fantasy. After the last of 12 astronauts left their boot prints in the lunar dust in 1972, the US government and taxpayers collectively declared, ‘been there, done that’. America had scored a dazzling point over the Soviet Union but at eye-watering cost, so the final three planned Apollo missions were cancelled.

For a while, our nearest neighbour in space seemed rather unappealing. But then, over recent years, came a series of discoveries about the lunar dust itself, suggesting that the Moon holds water and minerals that could conceivably help support a settlement, if anyone has the appetite to pay for it. So a new batch of missions is under way. China seems to be particularly eager, launching increasingly capable robotic craft that could pave the way for human flights, sometime in the 2030s.

In all probability, the next boots on the Moon will be Chinese. One of China’s leading space scientists told me how he even envisages opening lunar mines to extract valuable resources such as Helium-3. Throughout history, humanity has gazed at the Moon through different eyes. In the 1960s, it was the scene for Cold War rivalry. Now it is seen as a potential staging-post for longer journeys and as a rock waiting to be dug up and exploited.

Prof Mitrofanov says that there are scientific and commercial benefits to be had by building a permanent human presence on the lunar surface.

‘It will be for astronomical observation, for the utilisation of minerals and other lunar resources and to create an outpost that can be visited by cosmonauts working together as a test bed for their future flight to Mars.’

ESA and its industrial collaborators are developing a new type of landing system able to target areas far more precisely than the missions in the 1960s and 70s. The so-called ‘Pilot’ system uses on-board cameras to navigate and a laser guidance system which is able to sense the terrain while approaching the surface and be able to decide for itself whether the landing site is safe or not, and if necessary to re-target to a better location.

Europe is also providing the drill which is designed to go down to 2m and collect what might be hard, icy samples. According to Richard Fisackerly, the project’s lead engineer, these samples might be harder than reinforced concrete and so the drill will need to be extremely strong.

‘We are currently looking at the technologies we would need to penetrate that type of material and are looking at having both rotation and hammering functions. The final architecture has yet to be decided – but this combination of rotation, hammering and depth is a step beyond what we have already flown or is in development today,’ he told BBC News.

ESA will also provide the onboard miniaturised laboratory, called ProSPA. It will be similar to the instrument on the Philae lander, which touched down on the surface of Comet 67P last year. But ProSPA will be tuned to searching for the key ingredients with which to make water, oxygen, fuel and other materials that can be exploited by future astronauts.

The instrument will help scientists discover out how much of these critical resources are under the surface, and, crucially, whether they can be extracted easily.

Europe’s participation in the mission is due to receive final approval at a meeting of ministers in late 2016. It has the strong support of ESA and Roscosmos hierarchy, and the scientists involved in Luna 27 are confident that it is not a question of if but when humans go back to the lunar surface.

‘This whole series of missions feels like the beginning of the return to the Moon but it is also starting something new in terms of overall exploration of the Solar System,’ says Fisackerly.

Source: New Age