The DhakaTribune’s Abu Bakar Siddique reports from the banks of Teesta River on the effects of Indian river diversion on Bangladesh’s rivers and land

The Gajoldoba Barrage on the Teesta River looks like it is straight out of a movie set.

Tucked away in the far north of Bangladesh, one may witness here the holocaust that has followed in the wake of India’s policy of damming up rivers.

The river banks are lush and full of life on one side of the dam, where calm waters lap up against the thick walls.

Death marks the other side: barren earth dotted with the stubble of dry roots where once plants grew.

Located 80 kilometres from the Bangladesh-India border, it takes the better part of four hours to reach the Bangladeshi portion of the trans-boundary river.

Not even the faintest of trickles of water escapes the greedy mouth of the barrage, a result of India’s policy on the Teesta River.

It has become clear that the Indian government has diverted and withdrawn as much water as deemed necessary at Gajoldoba, unconcerned with Bangladesh’s needs or even those of the farmers downstream from the barrage.

The West Bengal irrigation minister told the BBC Bangla Service as much in an interview on March 14, 2014. Rajib Banerjee said the state had in fact been planning to expand farming coverage and would need more water for irrigation.

He pointed out that there was no legally binding treaty on Teesta water sharing, which according to him meant that India was free to use as much water as it saw fit.

That is what is happening at the moment, as a trip to the other side of the border clearly revealed.

Whatever water the river brings into Bangladesh is the result of accumulated rainfall and a handful of estuaries feeding into the Teesta flowing downstream from Gajoldoba.

India has been diverting Teesta water using feeder canals through Baikunthapur forest in West Bengal’s Jalpaiguri district towards distant areas of the state for irrigation.

There were high hopes that a water sharing agreement on the Teesta would be inked during the then Indian premier Manmohan Singh’s visit to Bangladesh in 2011. But the hopes were crushed to dust by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee who staunchly opposed such a pact.

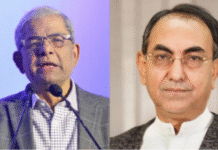

Prof Ainun Nishat who has long been involved with river water negotiations commented that India did not even have any regard for the ecology of the river in its own territory let alone the millions of Bangladeshis dependent on Teesta water.

“Our neighbour seems to have forgotten that there is a country downriver the barrage and they need water. They do not even think that the river itself has a life. If they did then they would have kept a minimum downstream flow,” said Ainun Nishat, a lead Bangladeshi hydrologist.

Impact on agriculture

The environs of the Teesta in its Bangladeshi portion turn almost into a desert during the dry season.

The Water Development Board says that the water flow falls drastically during the dry season, and has been lean of late.

“This year, we have seen 935 cubic feet per second (cusecs) of water during the 2nd 10-day tenure of March,” said the Bangladesh Water Development Board.

While, during the same period last year, the water flow at Dalia point was only 312 cusecs.

But between 1973 and 1985 when Gajoldoba did not start operations, the average water flow at the same point was 5,149 cusecs.

The Boro farmers dependent on irrigation projects based on Teesta water suffer greatly because they are simply deprived of water. This leads them to use shallow and deep tube wells exploiting ground water but at the same time raising the cost of production.

“I was forced to set up a shallow pump to irrigate my 5 acres of boro although there is a canal of the Teesta Irrigation Project just adjacent to my field,” said Monsurul Islam, a farmer of Jaldhaka upazila of Nilphamari district.

Similar to Bangladeshi farmers depending on Teesta water, the farmers of Haldibari, located downstream from Gajoldoba but still in India, also suffer.

Subol Sarker, living in the area said: “We are not suffering as much as Bangladeshi farmers. But I also set up shallow pumps to dig out underground water to ensure irrigation during the dry season.”

On the other hand, the farmers lucky enough to have lands adjacent to the canals carrying water from the Teesta get enough to irrigate their land.

Moloy Dey of Nirmal Palli village near Gajoldoba said: “Water for irrigation is not a problem in these parts. We always get Teesta water through the canals.”

Paresh Rajbonshi at Gatebazar of Jalpaiguri district echoed Moloy Dey.

“During monsoon, we get enough from rainfall. And in the dry period, we get water from Teesta canal for Rs200 (about Tk235) per acre for the Boro season,” he said.

Mir Sajjad Hossain, a former member of the Joint Rivers Commission said: “What Bangladesh receives during the dry season is the accumulated flow of ground water discharge and run-off from small channels and creeks but certainly not Teesta flow.”

Shifting agriculture

Farmers across the northern districts, especially those in

Lalmonirhat, are shifting away from the water-dependent Boro paddy and switching to maize and tobacco.

According to the Department of Agriculture Extension, this year around 15,000 hectares of Boro land shifted to cash crops like maize and tobacco in Lalmonirhat.

“The cultivation of maize and tobacco increased by 4,000 and 4,500 hectares while the boro decreased by about 15,000 hectares,” said Safayet Hossain, deputy director of Lalmonirhat agriculture extension. “This is a threat to food security.”

Source: Dhaka Tribune