IN THE years after September 11th 2001 and the “axis of evil”, a certain set of right-wing think-tanks in Washington (those who bothered to look at Bangladesh) worked out a pet theory. They prophesised the rise of a small Islamist party that would one day demolish Bangladesh’s secular traditions and create an Islamic state—not by revolution but by the ballot. “One man, one vote…one time”, as they had it.

It always sounded a bit outlandish. Since last week, it looks like pure tosh. A High Court in Bangladesh ruled that the country’s biggest Islamist party, the Jamaat-e-Islami, is unfit to contest national polls scheduled for later this year. The Supreme Court, after hearing Jamaat’s plea on August 5th, refused to issue a stay on the High Court’s ruling. It had found for a group of petitioners, led by the head of the Bangladesh Tariqat Federation (a smallish Islamic political party), who argued that Jamaat’s charter violates Bangladesh’s constitution and party-registration rules. Indeed the charter does not recognise parliament as the sole institution to pass laws; it bars non-Muslims and women from leading the party; and it has party offices abroad—each an apparent violation. Bangladesh’s Election Commission said that it would cancel Jamaat’s party registration.

The legal upshot is that Bangladesh’s third-biggest political force will not be able to contest elections, unless the Supreme Court takes a different view on the matter (which appears unlikely). The other way back in, probably equally unlikely, would be if Jamaat were to make fundamental changes to its charter and then register afresh with the Election Commission. It is unclear whether Jamaat, the religious party that serves as a standard-bearer for Saudi Arabia’s austere strand of Islam in Bangladesh, is prepared to jettison any of its core principles, including its commitments to an Islamic state and to enforced gender inequality.

The chief political consequence of the ruling, if it is upheld, is that the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) has lost its traditional ally, who had joined it in a ruling coalition from 2001 to 2006. The BNP has been acting as if this is a big deal. Over the years it has fashioned the myth that Jamaat is “indispensable” as a partner on the campaign trail. But this is to overlook the current state of play. The BNP on its own has done extremely well in recent mayoral elections, where it has been demolishing candidates backed by the ruling party, the Awami Leage (AL), including in Gazipur, the core of the country’s industrial belt and the AL’s second-safest constituency. The BNP is confident of victory and after seven years out of power, it is itching to turn the tables on the AL. And the BNP knows that history is on its side—no government has ever won a second term. Any extra edge that Jamaat might have offered them will be sorely missed.

The other salient fact is that today’s Jamaat, which had opposed the birth of Bangladesh back in 1971, is now fighting for its very survival. Many of its leading politicians had collaborated with the Pakistani army to prevent the creation of the state that is now prosecuting them, more than four decades later. Since the start of 2013, the International Crimes Tribunal, a domestic court tasked with punishing crimes committed in 1971, has sentenced four prominent Jamaat leaders to death for murder, mass murder, rape and religious persecution. A handful of other leaders, including the head of Jamaat, Motiur Rahman Nizami, are likely to join their ranks before the end of the year.

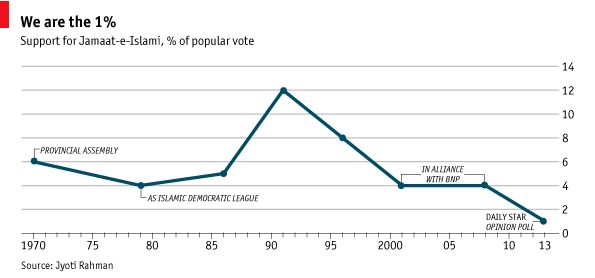

Quite apart from the contemporary BNP-AL dynamic, the reek of history from 1971 seems to be sticking to the Islamists of today. In a recent opinion poll, only 1% of respondents said they would vote for Jamaat. This compares with an actual 4% share of the popular vote in the 2008 general election, and a peak of 12%, which they won in 1991 elections (see chart below).

Part of their recent decline in popularity might have to do with the fact that the government has jailed Jamaat’s second-tier leaders. Many of its leaders at the local level have gone into hiding to avoid arrest. Bangladesh’s foreign minister, Dipu Moni, has taken to calling the Jamaat a terrorist organisation.

The AL has been murmuring about imposing an outright ban of Jamaat, ever since they changed the constitution in 2011 in order to make it possible to dismantle religion-based parties. But the threat is hollow. The government fears a violent response and knows well enough not to push its political enemies, who retain Saudi support, all the way underground. The AL is already struggling to keep public discontent at bay. The state’s security forces have killed at least 150 protesters and injured another 2,000 since February, according to a report by Human Rights Watch. Over the weekend, the AL tried to reassure diplomats and donors that it does not intend to ban any political party.

The months ahead will be marked by further flashpoints, as appeals and further sentences at the war-crimes court continue to roll in. People close to the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, say that she will be keen to limit the number of executions of convicted war criminals, even as she strives to ensure that her party can be seen to have delivered on its earlier election promise: to wrap up the prosecution of war criminals during the five-year term.

And so the next general election, which will be the sixth time that Sheikh Hasina and the BNP’s Khaleda Zia have squared off since 1991, will not feature starring roles for any of Bangladesh’s prominent political Islamists. The only big politicians to offer their prayers ahead of these elections will be paying their respects at the shrine of the great Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal. (This is exactly the sort of ministration that Jamaat’s orthodoxy forsakes.)

India will be hoping that Sheikh Hasina manages to defy precedent and win re-election. She would then begin a term that could make her South Asia’s longest-serving prime minister (albeit through non-consecutive periods in office). Amazingly, if she should fail to win this distinction, then Khaleda Zia will be able to claim it for herself.

One reason to hope that Sheikh Hasina keeps her government in place is that if she were to fail, then everything would look like business as usual for Bangladesh. The pendulum would swing the other way, as it always has. The BNP would regain power and the ability to rehabilitate its disgraced ally. As every prior government has done, it would declare that much of what happened under its opponents’ direction, including the sentences handed down by the war-crimes tribunal, were null and void.

Source: The Economist