LAST month a retired Hindu schoolteacher named Dinanath Batra, who had brought a lawsuit against me and Penguin Books, India, succeeded in getting my book, “The Hindus: An Alternative History,” withdrawn from publication in India. The book, the court agreed, was a violation of India’s blasphemy law, which makes it a crime to offend the sensibilities of a religious person.

Within hours I was receiving hundreds of emails from colleagues, students, readers, high school friends and even complete strangers — in the United States, India and beyond — commiserating with me in my dark hour. But their sympathy, while appreciated, was also wasted: I was in high spirits.

I have devoted my entire academic career, going back to the 1960s, to the interpretation of Hinduism and Indian society, and I have long been inured to the vilification of my books by a narrow band of narrow-minded Hindus.

Their voices had drowned out those of the broader, more liberal parts of Indian society; it reminded me of William Butler Yeats’s line: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.”

What is new, and heartening, this time is that the best are suddenly full of passionate intensity. The dormant liberal conscience of India was awakened by the stunning blow to freedom of speech that had been dealt by my publisher in giving in to the demands of the claimants, agreeing to take the book out of circulation and pulp all remaining copies.

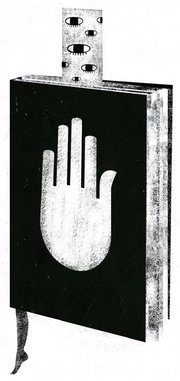

I think the ugliness of the word “pulp” is what struck a nerve, conjuring up memories of “Fahrenheit 451” and Germany in the 1930s. The outrage had been pent up for many years, as other books, films, paintings and sculptures were forced out of circulation by a mounting wave of censorship.

My case was simply the last straw, in part because of its timing, just when many in India had begun to view with horror the likelihood that the elections in May will put into power Narendra Modi, a member of the ultra-right wing of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

If Mr. Batra’s intention was to keep people from reading the book, it certainly backfired: In India, not a single copy was destroyed (the publisher had only a few copies in stock, and those in bookstores quickly sold out), and e-books circulate freely. You cannot ban a book in the age of the Internet. Its sales rank on Amazon has been in single-digit heaven. “Banned in Boston” is a selling label.

Attention has now shifted, rightly, to the broader problems posed by the Indian blasphemy law. My case has helped highlight the extent to which Hindu fundamentalists (Hindutva-vadis, those who champion “Hindutva,” or “Hindu-ness”) now dominate the political discourse in India.

Two objections to the book cited in the lawsuit reveal something about the Hindutva mentality. First, the suit objects “that the aforesaid book is written with Christian Missionary Zeal.” This caused great hilarity among my friends and family, since I grew up in a Jewish family in Great Neck, N.Y.

But when I foolishly decided to set the matter straight — “Hey,” I wrote to an accuser, “I’m Jewish” — I was hit with a barrage of poisonous anti-Semitism. One correspondent wrote: “Hi. I recently came across your book on hindus. Where you try to humiliate us. I don’t know much about jews. Based on your work, I think jews are evil. So Hitler was probably correct in killing all jews in Germany. Bye.”

It’s hard to have a religious dialogue with someone who begins the conversation like that. I was doing better in my role as a Christian missionary.

But there is a bitter irony in this mischaracterization of my religion, since Christian missionaries are actually a part of the problem.

The Victorian Protestant British scorned Hinduism’s polytheism, erotic sculptures, spirited mockery of its own gods and earthy mythology as filthy paganism. They also preferred the texts created and perpetuated by a small, upper-caste male elite, and regarded as beneath contempt the vast oral and vernacular literatures enriched and animated by the voices of women and lower castes. It is this latter, “alternative” Hinduism that my book celebrates throughout Indian history.

Many of the Hindu elite who worked closely with the British caught the prejudices of their masters. In the 19th century, those Hindus lifted up other aspects of Hinduism — its philosophy, its tradition of meditation — that were more palatable to European tastes and made them into a new, sanitized brand of Hinduism, often referred to as Sanatana Dharma, “the Eternal Law.”

That’s the Hinduism that Hindutva-vadis are defending, while they deny the one that the Christian missionaries hated and that I love and write about — the pluralistic, open-ended, endlessly imaginative, often satirical Hinduism. The Hindutva-vadis are the ones who are attacking Hinduism; I am defending it against them.

The Victorian factor also accounts for the Hindutva antipathy to sex. (Here it is not irrelevant that India recently passed a law criminalizing homosexuality.) The lawsuit objects that my “focus in approaching Hindu Scriptures has been sexual in orientation.” In my defense, I can tell you there is a lot of sex in Hinduism, and therefore a lot of puritanism in Hindutva; where there are lions, there are jackals. The poems and songs that imagine the god as lover, like the exquisite statues of goddesses, are a vital part of the religion of those Hindus who did not cave under the pressure of colonial scorn.

But I must apologize for what may amount to false advertising on my behalf by Mr. Batra, who pronounced my book “filthy and dirty.” Readers who bought a copy in hope of finding such passages will be, I fear, disappointed. “The Hindus” isn’t about sex at all. It’s about religion, which is much hotter than sex.

Source: NYTimes